Fifty-seven pieces of licensure compact legislation enacted in 2023; 290 enacted since 2016.

By Jessica Thomas and Kaitlyn Bison

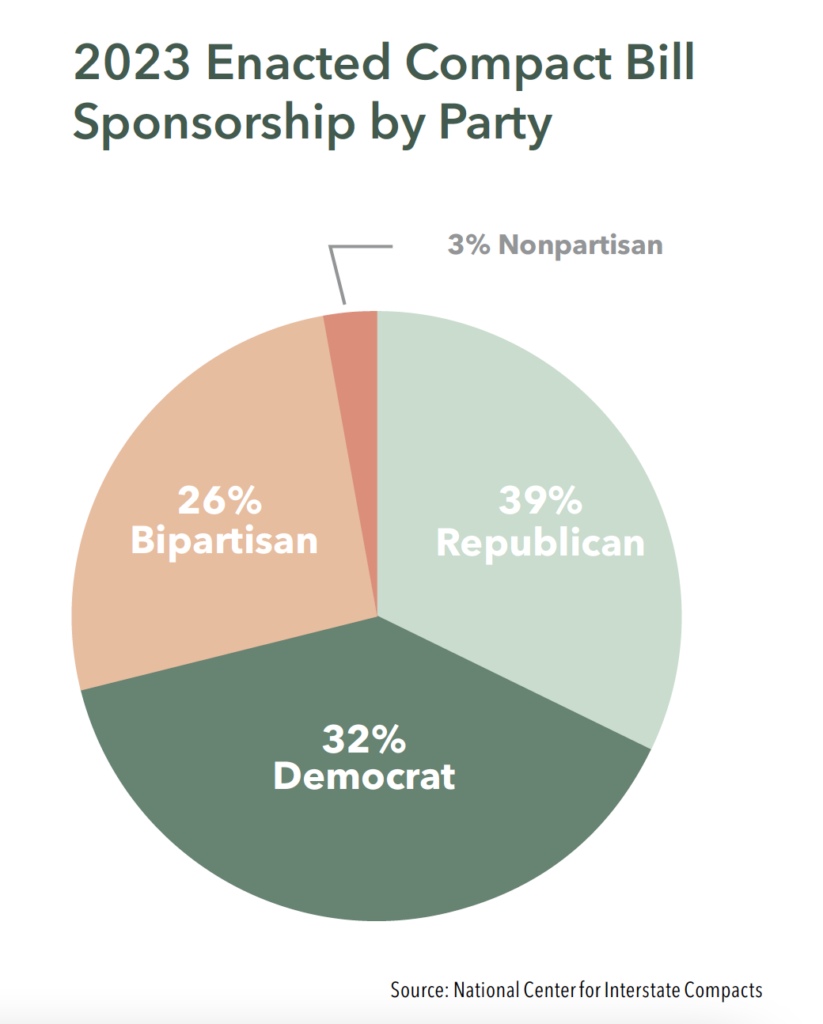

A recent uptick in the number of newly enacted licensure compacts has come as result of support from both sides of the aisle. The rise in these compacts, which establish mutual agreement between member states for professional licensure, offer state legislatures an opportunity to safeguard state sovereignty while also ensuring the quality and safety of services.

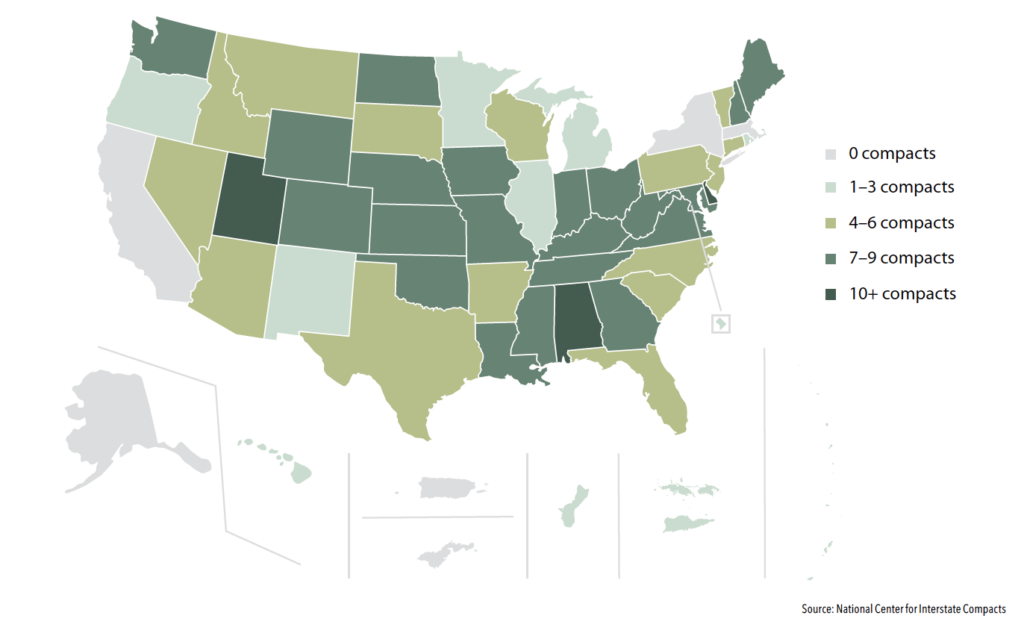

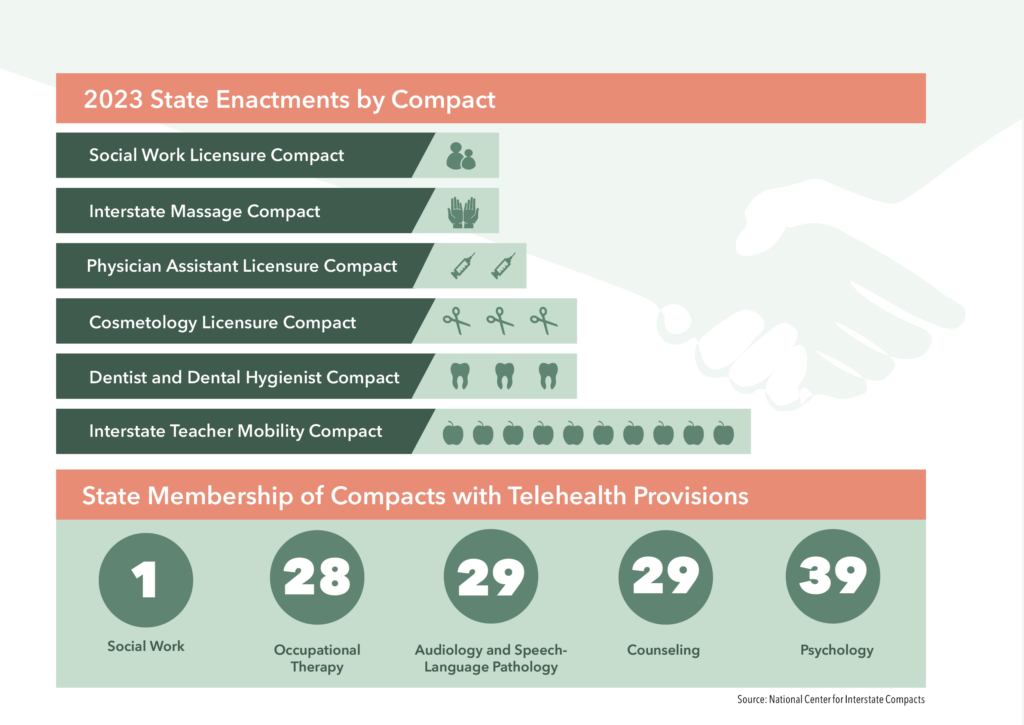

Since 2016, 290 pieces of licensure compact legislation have been enacted and, to date, 46 states, Washington, D.C., and three territories have enacted licensure compact legislation. A total of 15 professions currently have a compact available to states for enactment. In 2023, 57 pieces of compact legislation were enacted, with six new compacts becoming available for states to enact.

The National Center for Interstate Compacts, housed within The Council of State Governments, played a role in the development of all active licensure compacts. Through the work of NCIC, as well as policymakers sponsoring compact-related legislation, licensees in compact member states can more quickly obtain authorization to practice and get to work in other member states.

BIPARTISAN SUPPORT FOR WORKFORCE ADVANCEMENT

Compact legislation has experienced success in states with majorities from both sides of the aisle, while also having been sponsored by legislators from both parties. Support for state workforces proved to be a unifying theme among sponsors of 2023 compact legislation.

Rep. Michelle Caldier, a Washington Republican elected into the House in 2014, was grateful for the bipartisan support she received when sponsoring the Dentist and Dental Hygienist Compact, which is recognized in Washington as HB 1576. Resolving workforce issues in the state, especially within health care, has been a priority.

“I think trying to resolve Washington’s workforce issues is one of those things — across the board — that we acknowledge as one of the state’s goals,” Caldier said. “Breaking down the borders and allowing people from other states to come in and practice easily was one we could get a win on, so that was one of my focuses.”

Bipartisan support led to the enactment of the Cosmetology Compact bill in Arizona, where the successful HB 2049 was sponsored by Republican Rep. Tim Dunn.

“This is a bipartisan bill that promotes the flexibility for stylists to move between states,” Dunn said. “Arizona has a lot of winter visitors, and this could provide work for them when they visit.”

In Indiana, Democratic Sen. J.D. Ford coauthored both SB 251 ‚ the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact, and SB 160, the Counseling Compact. In addition to highlighting the bipartisan sponsorship of these bills, he explained ways in which he collaborated with his counterparts in the Indiana General Assembly to learn about and address community health needs.

“Access to care isn’t a partisan issue, it impacts all communities,” Ford said. “I think we were able to really come together well in that common goal with these compact bills.”

MILITARY FAMILY BENEFITS

Legislators often mention how compacts break down barriers for military families who move frequently and face challenges working in a licensed profession. Without a licensure compact, both military members and their spouses must navigate each state’s process for licensure.

Nebraska Sen. Carol Blood, a Democrat motivated to sponsor several compacts, believes they offer many benefits and opportunities to military families.

“Interstate compacts benefit others in specific licensure areas, but the reason I started working with these compacts is because of our military families,” Blood said. “Military families tend to move every two to three years, which means new schools, new doctors, new homes and more. This is one less headache for these families to deal with.”

Due to the increased military support, the Department of Defense facilitated the development of interstate compacts as a mechanism for ensuring the portability of professional licenses for military spouses. In September 2020, the Department of Defense entered into a cooperative agreement with CSG to fund the creation of new interstate compacts designed to strengthen licensure portability.

“[Compacts] are very positive for military partners who move to our state and people who are moving out of active service but want to continue working in a field where they are already licensed in another compact state,” said Colorado Rep. Mary Young.

PROFESSIONAL PERSPECTIVES

Many sponsors of compact legislation were licensed professionals themselves. The sponsors of Colorado HB 23-1064, the Interstate Teacher Mobility Compact, worked in the field of education and understand the barriers teachers face.

Young, a Democrat and former special education teacher and school psychologist, noted having her own experience with barriers to licensure as a teacher upon moving to Colorado. She admired efficiency and ease that compacts brought to licensure and wanted teachers moving to Colorado to remain in the profession.

“With the Interstate Teacher Mobility Compact, we can ensure that teachers who want to come to Colorado can do so,” said Colorado Rep. Meghan Lukens, a Democrat and former social studies teacher. “Giving teachers

the flexibility to live and work in any state in the compact benefits everyone. This compact will help incentivize teachers to stay teachers because of the flexibility that is provided to move to other states.”

As a former dentist, Caldier, like Lukens and Young, was also familiar with the compact profession she sponsored. She also recognized the need for license mobility and the need to address the shortage of dental hygienists in Washington. Although she continues to support the field of dentistry, Caldier’s support of compacts extends to other professions as a cosponsor on the Counseling Compact, the Nurse Licensure Compact and the Occupational Therapy Compact.

Licensure Compact Enactments by State and Territory

TELEHEALTH

Licensure compacts for health care professions can bring an added benefit to states: access to telehealth services. Ford said that compacts can “provide us with the opportunity to have more providers move to Indiana, but also greatly expand telehealth opportunities when you can meet with specialists in other states.”

Much of the general population can benefit from the increase in telehealth that compacts present. Communities that do not have access to health care providers, as well as people with low mobility due to a lack of public transportation or low accessibility, can all benefit from a rise in telehealth.

Of the 15 available licensure compacts, Audiology and Speech-Language Pathology, Psychology Interjurisdictional Compact, Counseling, Occupational Therapy and Social Work include provisions specific to telehealth.

Blood offered the example of Nebraska LB 1034, the Psychology Compact, as psychology is a licensed profession. If a patient moves or travels to a different state than where their psychologist is licensed, their care can be stalled or halted.

“Prior to that compact, Nebraska psychologists could not legally counsel someone over the phone if they were to have a mental health crisis in another state because that psychologist would not be licensed in that state,” Blood said. “With the compact, if the psychologist belongs [to the compact] as well as the state the patient is calling from, that psychologist can provide care for their patient.”

With the rise of telehealth and telemedicine, compacts are an important tool to meet the needs of patients. As more states join compacts, the pool of providers grows, and patients access to care expands.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR INCREASED STATE INVOLVEMENT

Legislators developed key takeaways throughout the process of introducing and enacting compact legislation. Attending informative events, involving key stakeholders, and working with colleagues from all parties enabled success.

Several legislators noted how collaborative convenings, such as the CSG National Conference, are useful for learning from other leaders who have sponsored compact legislation. At the 2022 CSG National Conference, Caldier learned about the Dentist and Dental Hygienist Compact while Kansas Sen. Pat Pettey was impressed by discussion on the Teacher Compact.

Pettey, a Democrat, and Washington Republican Sen. Ron Muzzall both suggest involving others, including other legislators and members of boards and professional associations.

“Engage stakeholders on an individual basis and engage with Department of Defense and organizations dedicated to supporting military spouses,” said Muzzall, who introduced Washington SB 5219, the Counseling Compact.

As the sponsor for Kansas SB 66, the Interstate Teacher Mobility Compact, Pettey recommended looking at compacts with an open mind.

“Take note of compacts your state may already be involved in,” Pettey said. “Make sure that you talk to other legislators on either side of the aisle about the legislation that you are considering introducing, as well as talking to your state board of education and your teachers’ associations. Doing early work to make contact with other parties will be helpful for when they actually introduce [legislation].”

More information on compacts can be found at the following website: compacts.csg.org. Policymakers interested in sponsoring a licensure compact can reach the National Center for Interstate Compacts via email at [email protected].