On Oct. 22, 1933, as many as 15 state legislators convened at the Penn Harris Hotel in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, as part of a shared interest in introducing harmony among the states. CSG Executive Director/CEO David Adkins addressed this meeting and the growth of CSG in a message recognizing the organization’s 90th birthday.

Continue readingExecutive Branch Contests Highlight Election Day 2023

General elections for governor, justice, and state House and Senate occur across six states Tuesday, highlighting notable Election Day 2023 contests. In an additional seven states, ballot measures are up for vote that address areas ranging from election spending and property taxes to project funding.

Continue readingMeet the 2023 CSG 20 Under 40 Leadership Award Recipients

The Council of State Governments is proud to announce the 2023 recipients of the CSG 20 Under 40 Leadership Award. Each year, CSG recognizes the dedication of 20 up-and-coming elected and appointed leaders from across the United States. These leaders exemplify strong leadership and a passion for public service.

Continue readingSwisher Pledges $500,000 to Development of the Emerald Trail

Swisher, the iconic family-owned brand of more than 150 years, committed $500,000 to the continued construction of the Emerald Trail, a 30-mile pedestrian and bicycle route system connecting downtown Jacksonville, Florida, with neighborhoods, schools, parks, restaurants, businesses and more.

Continue readingLiving on the Edge

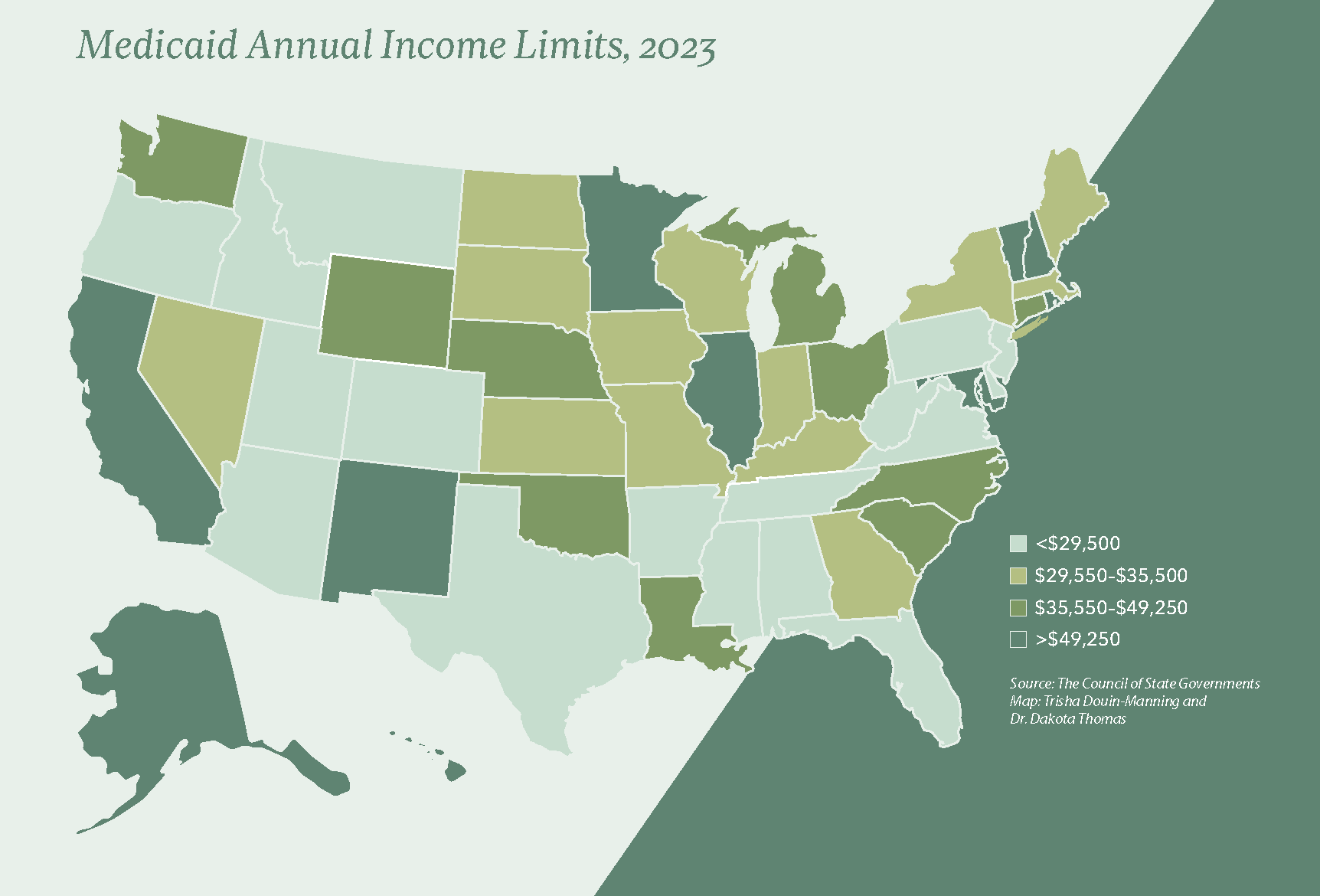

Public assistance benefit programs offer a safety net to more than 37 million low-income families. Yet, despite even the smallest increase in income or assets, individuals or families may be disqualified from certain programs. This sudden disqualification is a benefits cliff.

Continue readingSchoolhouse to Statehouse

Elected educators’ policy work places students first

By Maggie Mixer and Abeer Sikder

From classrooms to Capitols, a nationwide community of state leaders serve as educational advocates on their chamber floors. They drew inspiration from real-world experiences and outstanding students that left lasting impacts during their previous — and even ongoing — careers as teachers, professors and school administrators.

Despite having a diverse set of backgrounds and experiences, the policy work of nine state legislators is rooted in one common cause: students.

Kentucky Rep. Kim Banta, a former teacher, principal and assistant superintendent, noted that educators are deeply in touch with their communities and the day-to-day challenges faced by students and their families.

“Teaching is an amazing boot camp for most other things that you can do in life that might be stressful or difficult,” Banta said. “[Educators] have their fingers on the pulse of what the struggles are, what problems people are having … because you see every single segment of society [in schools].”

The 17-year teaching career of California Sen. Susan Rubio went beyond the classroom, as she helped students and their families navigate housing and food insecurity, language barriers and more.

“As an educator, I was exposed to so many of the issues our community members were facing,” Rubio said. “Early on, a few families came to me for support and help outside the classroom, letting me know they didn’t have funding for supplies … and I would try to connect them with [other] resources [too].”

Rubio said soon after she learned the true scale of the problem “and, as a teacher, [she] could only do so much.” Rubio decided she wanted to help her community from a broader platform. With access to more resources, she launched her first political campaign. Prior to joining the California Senate, she served Baldwin Park, California, for 13 years as a city clerk and city council member.

Other state leaders, such as Virginia Sen. Ghazala Hashmi, were driven to run for office due to specific challenges experienced in the classroom as an educator. Hashmi, who was professor at Reynolds Community College in Richmond, Virginia, also founded the college’s Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning. After teaching for nearly 30 years, she put her name on the ballot because she “saw the state government pulling funding and resources away from students and families, and [she] knew that we could do better for thousands of deserving students.”

Current and former students have been a continuous source of inspiration for these elected officials. While most gave up being full time educators to hold elected office, many still teach part time or make guest appearances at their district’s schools and agree that it remains one of the best parts of their jobs.

Indiana Sen. Andrea Hunley, who taught high school English before her 10 years as a principal, recounted being inspired by students organizing against gun violence, high schoolers’ talented navigation of artificial intelligence programs and a third-grade class’s sit-in protest for more recess time. According to Hunley, students’ creativity and enterprise are “leaps and bounds ahead of us” and ahead of the legislation currently in place.

Hunley’s experiences drove her not only to serve as an elected official but to also always focus on creating broad and innovative policy because “we’re legislating for the future and for future generations.”

“It’s like our legislation never caught up to where our kids are,” Hunley said. “If we legislate in a way that we think like teachers … we plant seeds for today so that they can bloom tomorrow. We would legislate very differently as we think about generational impact, which is what teachers do every single day.”

Once elected, many of these legislators continued to draw substantive lessons, as well as inspiration, from their time as educators. Among the most important skills, though, was interacting and communicating with others in an effective manner.

Hashmi compared serving constituents and students, discussing the importance of being “timely, responsive and informed about how to resolve constituent concerns.” She added that it has improved her ability to engage with colleagues as she strives to “focus on the nuances of arguments” and “bring as much background and information as [she] can to influence the understanding of others.”

Pennsylvania Sen. Dave Argall took a unique path compared to most other legislators, entering elected office before becoming an educator. While serving in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives and later in the Senate, he took night classes for 13 years to earn his master’s degree and doctorate in public administration.

As an instructor, Argall returned to teach night classes as a state and community college instructor. It was there he acquired the ability to concisely present complicated issues to his constituents.

“When you’re meeting with college students one night a week for 15 weeks, you learn how to condense a lot of information.” Argall said. “I think that practice has been really helpful to me [when] meeting with constituents at town hall meetings.”

Listening respectfully is another side of communication legislators learned from their classroom experiences. Indiana Sen. Fady Qaddoura teaches courses on civic engagement and executive leadership as an adjunct faculty member in Indianapolis. In his experience, receiving critique on projects in academia as a doctoral student and researcher taught him the important role that diverse perspectives play in the process of creating high-quality work.

“[This perspective] helps us build bridges of trust among legislators to understand that when we raise a question or concern, it is not politically motivated,” Qaddoura said. “It comes from a genuine concern about the policy that is being debated or discussed.”

Qaddoura’s approach helped shape how he interacts with other senators and last year contributed to colleagues nominating him for the Indiana Senate’s annual civility award.

Similarly, Iowa Sen. Jeff Taylor — even as a member of a majority caucus — said he works to listen to everyone on the Senate floor. After many years as a professor, academic and author, he believes that there is always more to be learned from others.

“I make it clear [to students] that they’re free to disagree if they don’t see things the way I see it; I’m not going to hold it against them,” Taylor said. “I think I borrow that approach of fairness and objectivity from the classroom while on the Senate floor and in committee meetings.”

Rubio found that her experiences listening to and balancing the different perspectives of 30 students in a classroom greatly informed her ability to “create policy that’s sensitive to everyone’s needs.” In a large, diverse state like California, this crucial skill has helped her understand where her community fits in massive, statewide bills.

Many legislators who held administrative positions, like principals and superintendents, reflected on how listening was one of many skills they learned as educators that improved their ability to collaborate, especially with colleagues across the aisle. Banta and several of her colleagues with backgrounds in education work hard to build consensus, which she attributed to their experiences in education environments where “it was never my way or the highway.”

“We [educators] tend to listen a little bit better and we tend to be problem solvers and we try to get everybody on board,” Banta said. “You always have to work with people and come to some kind of consensus [as a principal] and I think that transfers right into this job.”

Wisconsin Rep. Dave Considine described how the goal of educational environments and improvement, not perfection, informed his approach to collaboration. Considine, a special education teacher for nearly 30 years, credits the patience he has brought to the Legislature for enabling him to stay focused on moving forward — no matter how slowly.

“[Politics can be] a step forward, then maybe a step or two back, and then another big step forward, and then maybe half a step back,” Considine said, drawing parallels to his teaching tenure. “You don’t change behaviors overnight. That was my specialty, and so I’m used to that.”

For many legislators, education offered an avenue to acquire strategies now utilized for policy development. Curriculum development is among those strategies. Often data driven, this specific process is one that helped prepare many of the nine legislators for life in office.

According to Delaware Rep. Sherae’a Moore, a former English teacher, data-driven curriculum development “translates well into the legislative process.”

“Evidence-based policymaking is crucial for achieving effective and equitable outcomes and [limiting] unintended consequences,” Moore said. “By being on the front lines, we understand that the educational systems are intricate, involving multiple stakeholders and layers of governance. This experience prepares us to navigate complex policy landscapes as we are the ones witnessing the impact of policies directly in the classroom.”

Moore has integrated this approach into her work in the statehouse by using “data to drive any type of decision making, before [she] even drafts legislation,” to ensure that the policies she proposes fit the needs of her constituents.

Educational experiences can also form legislators’ outlooks on the connections between different issues. Argall described sharing the view of his predecessor — another long-time educator — on the “spaghetti bowl theory of government” that “everything is related to everything.”

For Argall, the perspective of his predecessor impacted his approach to identifying and creatively addressing problems. In 2003, After seeing the “very tight correlation” between the availability of good jobs and a community’s education level as a community college instructor, he organized the conversion of an abandoned junior high school into a community college center.

“The building had been around since, I think, the 1920s, and was just sitting kind of sad, empty and beginning to deteriorate,” Argall said. “Sometimes in this job, you just need to bring the right people to the table.”

Through the combined efforts of the community college, the local government, Argall’s office and a private foundation, they not only converted the building into a new education center but also funded the incoming class’s tuition.

“I can still see the faces of the parents when [former Pennsylvania Gov. Mark Schweiker] made the announcement about free tuition for two years,” Argall said. “The parents understood the power of that moment and we literally changed lives that day.”

The project helped “breathe new life” into local students’ futures and the surrounding community, a central goal of Argall’s efforts around Pennsylvania, which have also included a series of anti-blight laws.

The transition from education to elected office was not necessarily a career switch for these nine legislators. Rather, it presented a new side of the same path of service that they were already walking. Education placed them on the front lines of their communities and helped teach them how to effectively work with and for others — lessons that they have brought into elected office to continue to serve current and future generations.

“We give that level of support to our kids because we genuinely, and in a loving and compassionate way, want our kids to be better than us,” Qaddoura said. “Imagine if you can extend that feeling — to give them the best of who you are so that they can live better lives — to the rest of the population and to your fellow citizens.”

Evolving CSG, Dept. of Defense Initiative Continues Enhancing Accessibility for U.S. Military, Overseas Voters

By Morgan Thomas

The Overseas Voting Initiative continues to conduct research, analyze Uniformed Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act voter data, and cultivate dialogue surrounding innovative strategies to enhance voter accessibility through the act.

The OVI is a collaboration between The Council of State Governments and the Department of Defense Federal Voting Assistance Program focused on improving voting access for U.S. military and overseas voters.

Service members, their families and other U.S. citizens residing overseas face many challenges when trying to obtain and cast their ballots in U.S. elections. Service members deployed to remote areas, students studying abroad or government workers working abroad in difficult-to-access locations must overcome hurdles to exercise their right to vote. Mail operations can be intermittent or even nonexistent in some locations. Power, and therefore access to electronic communications, can also be unreliable.

Voters facing any of these challenges are protected under the Uniformed Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act, which is also commonly referred to as UOCAVA. UOCAVA was enacted by Congress in 1986 and provides U.S. citizens and their eligible family members a legal basis for absentee voting requirements. Each U.S. citizen abroad faces unique challenges, making it difficult for both the voter and election officials.

The Overseas Voting Initiative works with local and state election officials who comprise its OVI Working Group. The Working Group is divided into subgroups that focus on specific areas of interest centered on improving voting accessibility for UOCAVA voters. Through these subgroups, the OVI has conducted research, promoted technology and policies, informed state policymakers about overseas voting issues, and shared best practices with state and local election officials and other stakeholders. Some critical areas of research include:

UOCAVA balloting solutions.

Improving communications and connections between UOCAVA citizens and their election offices.

Making voter registration easier for UOCAVA citizens.

Considering how DOD digital signature capabilities can facilitate document signing by certain UOCAVA voters.

Examining how the ballot duplication process can be improved through transparent standard operating procedures and new technologies.

In addition to these areas of research, the OVI has also created a data standard for the Election Administration and Voting Survey, or EAVS, Section B Data. This standard allows election officials and the Federal Voting Assistance Program to conduct a deeper analysis of UOCAVA voter behavior. The Working Group analyzes and makes recommendations for changes to EAVS Section B Data to improve the survey to serve the voters and election officials better.

Now in its 10th year, the OVI has conducted more than 27 Working Group meetings in 14 states and U.S. territories, one U.S. Embassy, and visited 11 military installations. In early spring 2024, the OVI will be releasing a series of modules identifying best practices for communicating with military service members, their families and citizens living abroad.

Nine Decades, Four Distinct Regions

CSG ‘laboratories of democracy’ remain steadfast champions of state leaders. Explore the history and development of The Council of State Governments’ presence in the now flourishing Eastern, Southern, Midwestern and Western regions.

Continue readingEmpowering Native Voters

New Mexico secretary of state works collaboratively to improve elections for Tribal communities.

By Lexington Soures

When New Mexico Secretary of State Maggie Toulouse Oliver served as Bernalillo County clerk, she learned firsthand the challenges of translating election language. In the Navajo Nation, where Diné bizaad is spoken, no direct translation exists for Republican or Democrat.

When Toulouse Oliver attended her first Navajo Nation chapter meeting, she learned more about how election and political terms may differ from community to the next. While one community may identify a Democrat as a “donkey rider,” another may use the phrase “someone who walks with a donkey.” This experience led her to prioritize word choice.

“That was that was one of the big, mind-blowing things for me — how do we communicate,” Toulouse Oliver asked. “What terminology do we use even within the context of the Navajo language to make sure that that idea is communicated accurately? That is one of our big challenges.”

Toulouse Oliver acknowledged that assimilation and language eradication occurred in many Native communities. However, some voters maintain a traditional lifestyle.

“I have people in New Mexico that live in hogans with no running water and no electricity,” Toulouse Oliver said. “They live their very traditional way of life and that has not changed in their lifetime. So, what do we want to do? Leave these folks behind when it comes to the voting process? No, we have to come to them.”

Before 1948, the New Mexico Constitution did not allow certain Native people to vote. Miguel Trujillo, a member of the Pueblo of Isleta and a World War II Marine Corps veteran, then stepped in to challenge the constitution’s language. Prior to Trujillo coming forward, voting rights were denied to Natives who did not pay private property taxes on reservations despite having paid all state and federal taxes. With the right to vote eventually secured, Native voters faced limited access to voting locations and a lack of translated voting materials that included instructions, notices and even ballots.

While some counties complied with federal law and Department of Justice intervention, others were slow to adapt their processes.

“There’s sort of a history of really needing to get with it in terms of complying with federal law,” Toulouse Oliver said. “Fast forward to today, we have one letter of agreement left in existence for one county. We have the Native Voting Task Force in my office and then we passed the Native American Voting Rights Act this year.”

This year, New Mexico’s Legislature passed HB 4, covering a variety of voting rights issues including the first Native American Voting Rights Act. The bill expands a nation, tribe or pueblo’s ability to apply for amended voting locations and a secure ballot drop box, and allows voters to use government buildings as their mailing address.

“We gave them the opportunity to ask for and receive a secured monitor container, also known as a drop box, for once they receive that ballot, especially if they receive it at that tribal government building,” Toulouse Oliver said. “They can also deposit the ballot back at the government building. They don’t necessarily need to send it back through the mail.”

Local tribal governments were also provided much more flexibility through the bill. As a result, they can now establish the site of their polling locations, in addition to choosing where and how long early voting takes place.

“We’re hoping all of those things go a long way towards really improving some of those ballot access challenges,” Toulouse Oliver said.

Implementation is the secretary of state’s next major challenge. She and her office plan to provide resources to Native communities that include the new options and work to determine what is best for each community.

Otero County Clerk Robyn Holmes said the bill helps solve some challenges her county faces, such as a central address for ballot delivery. Otero County has around 12,196 Native voters who live on the Mescalero Apache Reservation.

“We work as county clerks with the Secretary of State’s Office and we come up with things that we feel will help voter outreach and get people out to vote,” Holmes said. “For that, we get along very well with our secretary of state. Our legislator’s listen to us and subsequently they pass the laws.”

Holmes said this hasn’t always been the case, though. However, over time, and despite party differences, clerks and legislators have been able to work together with Toulouse Oliver to communicate voters’ needs.

“We’ve been very fortunate with the offices of the secretary of state and clerks working so well together. It’s not always perfect, but for the most part, we can work it out and make it work for everybody,” Holmes said. “It’s different when you have large cities in one county and then you have very small, rural counties with two people working in their offices. It’s hard to implement bills and policies and procedures exactly the same for everybody.”

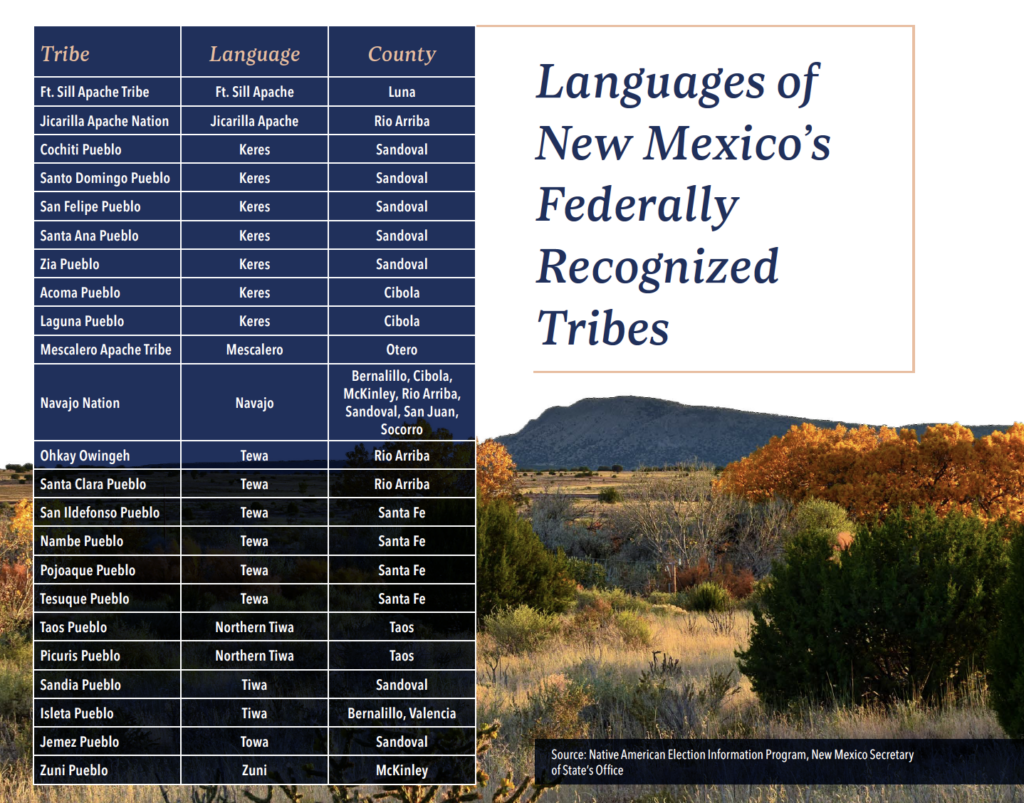

Toulouse Oliver recognizes that policy cannot be copied and pasted between New Mexico’s 23 federally recognized tribes, who speak eight different languages. The Native American Voting Rights Task Force was created in 2017 by the secretary of state to better connect with the needs of New Mexico’s three main tribes, including the Navajo Nation, the Pueblos and the Apache Tribes. The task force has representation from all of these groups, as well as an urban Native representative, but limits membership to a few members to remain productive. Members collaborate to inform the Secretary of State’s Office on areas of outreach and improvement, in addition to useful and appropriate language and messaging.

“We don’t want to copy and paste, first of all,” Toulouse Oliver said. “We don’t want to treat all of our tribal areas the same and all of the individuals because they have different cultures, different languages.”

While Holmes doesn’t need to translate ballots, her office does translate the portion of the proclamation affecting the reservation. These translations are recorded and played through the local radio station.

Because each tribe has a unique voting culture, including who can vote and what positions are open for election, it is important to approach each tribe with their culture in mind, according to Toulouse Oliver.

“There are just so many culture and language ins and outs that, as a white woman from Albuquerque, New Mexico, I am not the expert, nor am I ever going to try to be, nor am I ever going to try to superimpose what I think works in tribal areas,” Toulouse Oliver said. “I want folks to tell us what works in [their] community. What creative ideas do you have? How can we invest in those? How can we live those? That’s kind of the work that [the task force members] do.”

Despite progress, Native voters continue to face challenges, including limited ballot collection services, language translation and the digital divide. A report by the Native American Rights Fund found voting barriers typically fell under 11 categories, including geography, infrastructure concerns, nontraditional addresses and IDs, and the digital divide. The 2020 report found only 66% of eligible native voters across the nation are registered.

Toulouse Oliver uses buildings of cultural importance, like chapter houses in the Navajo Nation, to help increase access to polling locations.

“We use schools, we use other public buildings where available, but even then, you’re often talking about an individual having to drive 50 to even as many as 200 miles to get to the nearest in-person polling place,” Toulouse Oliver said. “We’re trying to expand — as much as we can — mobile early voting units [that travel] to these communities to be there for two or three days to a week during the early voting period.”

Because many who live on reservations receive their mail at a post office box or reside in remote, nontraditional areas without valid U.S. mailing addresses, New Mexico law allows voters to describe their addresses.

“We’ve done a really good job in New Mexico for years at addressing the issue of not having a standard physical address,” Toulouse Oliver said. “You can literally draw a map, write a description or say, ‘I live three streets down from the giant cottonwood tree after you get off of the exit at Highway 85.’”

While voters are able to describe their address, this can be challenging when ballots or other voting materials need to be delivered. Toulouse Oliver said mail delivery can be infrequent, or that individuals may not receive mail at their home. In New Mexico HB 4, the Legislature addressed issues regarding ballot delivery, allowing individuals to use their local tribal government building as an individual’s mailing address. Toulouse Oliver said this eases the process because the U.S. Postal Service delivers to every tribal government building in the state.

“One good thing that came out of this last session was that the Legislature passed the law that on reservations they could have one location, like at their community center or wherever they designate,” Holmes said.

“They’ve created this law that allows our reservation to say, ‘Anybody that wants to request a ballot that was on the reservation, you can have it mailed back to our community center and we’ll get it to you,’ as opposed to going to their address where apparently they feel like they don’t get their mail all the time.”

Native voters living in urban areas face challenges that are different than those on reservations. Based on the population, some urban areas are required to have translated ballots or a translator on call. Many urban native voters have access to broadband internet and are aligned with their nonnative neighbors, but there may be more cultural challenges.

“I think there is a particular part of the Native community that may live physically within an urban area. They live in Albuquerque, New Mexico, or Gallup, New Mexico, or Farmington, but they still consider their whole chapter and maybe their parents’ or their grandparents’ residence [to be] where they actually live, where they are from,” Toulouse Oliver said. “In many ways, it’s interesting to see our urban Native voters needing to go back to that place of origin in order to vote or to apply for and get an absentee ballot. The challenge there then is just going like we would do with any other group. What is what makes you interested in wanting to vote? How can we make it easier for you to register and get your ballot?”

Another challenge is the size and resources available for some communities. A tribal community’s size or economic resources may lead them to be more invested in federal elections, or the opposite may be true. Toulouse Oliver added that opinions on the importance of elections may differ even within communities, increasing the challenges of civic education.

Many of these smaller communities also struggle with access to broadband connectivity or phone service. This creates an additional challenge for election officials.

“How do we make sure those voters have information and access to the ballot box in the same way that a voter who lives in Gallup or Shiprock,” Toulouse Oliver said. “Those are the kinds of challenges we’re trying to navigate.”

One program tackling this challenge is the Native American Election Information Program. Created in 1988, the program facilitates voter education programs in counties with the largest Native populations. The program educates communities on the election process, upcoming elections, and provides election assistance for both tribes and county clerks to ensure compliance with federal and state law.

Toulouse Oliver increased the number of staff to better cover the needs of Native communities. The liaisons translate necessary documents into both the appropriate language and the correct media. For example, publication requirements necessitate the use of radio in some communities.

“It’s a lot of work for two people, but they do an amazing job,” Toulouse Oliver said. “They’re the ones who are physically out there in the communities, hearing from those tribal leaders on what they need, what we need to be doing better and what is something that they need from us versus what is something they need from county government. Sometimes we can all three work together to get something accomplished.”

In counties with a larger Native population, a tribal liaison works with the county clerk to provide tools or resources. As well, while not required, each Native community hires poll workers from their community. These workers provide a cultural connection and can help with any language or assistance needs. Toulouse Oliver said this lessens the stress and intimidation of voting, especially for new or infrequent voters.

Holmes said she does not work with a liaison, but she has built close relationships with community members, like an attorney on the reservation. For voter drives, a member of the New Mexico Secretary of State’s Office joins Holmes’ office.

“I’m friends with the attorney up there,” Holmes said. “We make sure we have an open dialogue between us. If they need anything or if we need something, [we’re both very good to accommodate each other].”

Looking ahead, Toulouse Oliver hopes to expand her office’s work with the Native community. A facilitator will join the Native American Voting Task Force to help the group explore programs and funding for the future. Toulouse Oliver said the successes, or failures, of this “regearing” phase will determine future programs.

The work of the Secretary of State’s Office with the Native community can, in a larger sense, be applied to other minorities. Toulouse Oliver said that while not all marginalized communities may face the same challenges, other voters benefit from the lessons learned from listening to communities’ needs and allocating appropriate resources to them.

“As an elected official, you have to be open to saying, ‘You tell me what you think your community needs. I’m not here to tell you what I think it needs,’” Toulouse Oliver said. “If it’s not me, who can I give tools and resources to that are needed to be that person, that messenger. Not all marginalized communities have the same challenges. [We’re] not just taking that cut and paste approach.”

Social Michigan

Facing social media’s rapid advancement, the Great Lakes state sets the tone with support from a multitude of resources and strategies

By Trey Delida

It’s safe to say that social media has impacted nearly everyone’s day-to-day lives, both personally and professionally. This decades old technology — now dating back to 1997 — has permanently altered the way we communicate, share and receive information.

As rapid advancements in the field continue, government organizations remain in pursuit of fully understanding social media, its ever-changing nature and all it has to offer, while simultaneously trying to reap the benefits of its dominance in society.

In 2023, there are approximately 308 million social media users in the United States alone. So, how do state governments intend to continue navigating this growing, dynamic juggernaut?

When looking at the states, there is one that seems to have its finger on the pulse. Boasting millions of followers across its platforms, the state of Michigan’s award-winning social media program utilizes a plethora of tools to engage, support and provide processes for staff managing social media accounts across its many state departments.

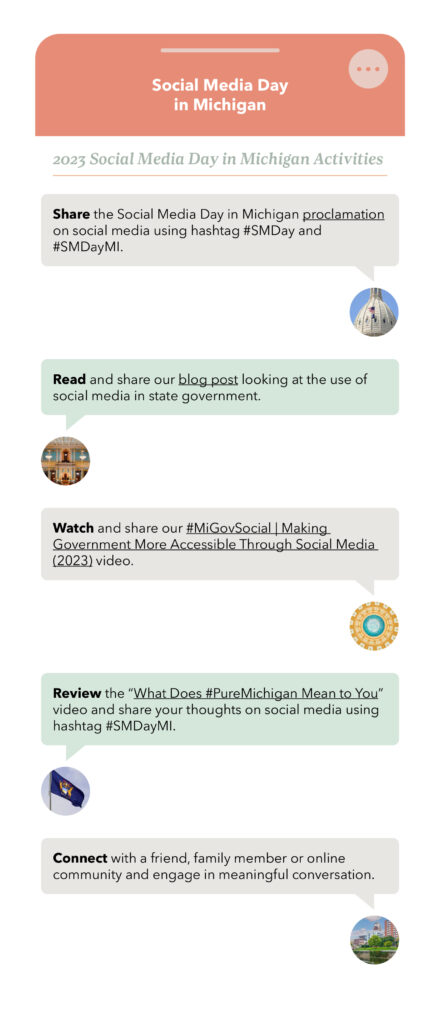

Michigan was ahead of the curb when it came to embracing social media, even adopting a statewide “Social Media Day,” celebrated annually on June 30. The Great Lakes state was one of the first states to adopt a centralized social media strategy for its executive branch departments, which now supports more than 300 staff managing more than 800 state-affiliated accounts across 11 different platforms.

According to Andrew Belanger, statewide social media director and digital content administrator with the state of Michigan, the state’s centralized governance strategy for social media has been key to fostering a proactive statewide digital footprint.

“We believe governance is an important element to a strong and proactive social media program,” Belanger said. “Over the years we have developed numerous statewide resources that support our program and provide guidance to our agency teams as they manage their accounts.”

Through such resources, Belanger’s team established a statewide social media standard, developed social media guidelines and best practices, hosted routine trainings, and standardized many processes across the state that were once decentralized across agencies.

“From a centralized governance perspective, our program resources and processes have been helpful in establishing a baseline for our staff and our activities on social media,” Belanger said. “We reference these resources daily as our teams share content and engage with residents across the state, nation and globe.”

Michigan was one of the first to establish statewide social media policies, issuing its “Social Media Standard” in 2011. That particular document created guidelines for any state-affiliated account and established best practices for creating and using state-affiliated social media accounts.

The standard outlines everything state social media professionals may need, including how to request an account, properly deactivate or close an account, and how to recognize content that may be at risk for violating community and state guidelines.

“In addition to our social media standard, we created a social media guidelines book containing things that are subject to change based on platform functionality and best practice,” Belanger said. “The guidelines book addresses and outlines processes, shares tips and tricks and best practices, and helps guide staff as they manage their accounts and share content.”

Belanger added the state also developed statewide social media community guidelines and a customer use policy that identifies criteria for content moderation. The criteria are used for staff who are monitoring and engaging with user-generated content that may potentially violate state policy or the terms and conditions of a specific platform.

“Standardizing our community guidelines and customer use policy across agencies was a game changer for our agencies,” Belanger stated. “Independent of where staff work and what programs and services they support, our application of consistent statewide guidelines, and criteria, helps promote a unified user experience as users reach out and engage with us across agencies, platforms and accounts.”

Since 2016, Belanger has overseen the state’s entire social media program, including branding, best practices, training and enforcing statewide social media policies and standards. His support of government social media has led to him being featured in publications like USA Today, the New York Times, the Washington Post, U.S. News World & Report and more.

One of Belanger’s first projects was to establish a social media governance board. Now known as Michigan’s Statewide Social Media Governance Council, the council, comprised of members from all state departments and agencies, support him in guiding policy, branding, best practice, education and scaling of social media for the state.

“We found that it’s really important to have that regular touchpoint with all of our teams so they can provide feedback and suggestions on policy, training and best practice,” Belanger said. “During our council meetings, we also have dedicated time set aside to provide support and discuss content collaboration, and how we can best partner on interagency campaigns and high-level messaging coming out of the governor’s office.”

As part of Michigan’s effort to provide structure and support for agencies across the state, they are regularly reviewing and updating their approach to ensure they adhere to industry best practices. They continually monitor policies, standards and practices in other states, the federal government, and those of community partners and local governments.

“We are always looking for opportunities to improve our standards, guidelines and strategies to best meet our business needs and the needs of our constituents,” Belanger said. “Through the council, our collaborative approach to social governance, our commitment to service delivery and our focus continues to be on our users. We seek to provide users with the information they need on the platforms where they feel most comfortable.”

With streamlined processes in place, partnered with open lines of communication, Michigan maintains consistency with its digital footprint while ensuring the people who are running these social media accounts are equipped with the information, they need to create successful, on-brand content.

Consistent messaging is essential for public sector institutions. In a world where news can break to millions of people at any given moment, it is important for states to be able to tell their story and be able to share dependable information in real-time.

Social media is used as a daily source of news by 50% of Gen Z, 44% of millennials, 39% of Generation X and 24% of Boomers, according to a Morning Consult poll published in August 2022 and later reported by Statista. That same source reported that U.S. Congress members were utilizing social platforms heavily, sending out 477,586 posts on X, formerly Twitter, in 2021.

“Social media has played an important role in government communications over the last decade — we’ve seen it,” Belanger said. “Now, more than ever, we see the immediate impact it can have in disseminating information in real time. Whether it’s in times of crisis, a natural disaster, a public safety situation or public health emergency, social media will continue to play an important role in government communications.”

Belanger credits state leadership for recognizing social media’s value, which allowed Michigan to become one of the first states to embrace social media and roll out their policies.

“For a successful social media program, it’s important to have leadership buy-in and understand the value and the benefits that social media can provide,” Belanger said. “Being able to enhance transparency, communication, customer service, collaboration and information exchange in real-time and in times of crisis can help humanize the people, programs and services that government agencies provide.”

When it comes to developing these processes, Belanger said it starts by bringing people together, asking questions and sharing information.

“If you’re not having conversations with your team, other agencies or departments, start having them,” Belanger said. “Start by asking questions: What are other agencies doing? What do they have in place? How can we partner and collaborate?”

These questions can be a starting point for reviewing or updating your agency’s social media resources. As Belanger put it, social media is here and it isn’t going away anytime soon. Just like organizations and businesses across the globe, there is potential for governments to leverage this technology to connect and better serve their public.

“The platforms and the strategies we use may change, but the idea of connecting and exchanging information, engaging with our constituents, is not going to go away,” Belanger said. “We need to adapt and evolve as the social landscape continues to change.”