By Bill Swinford

In the aftermath of the most recent wave of mass shootings around the U.S. brought to the forefront following the tragedies in Uvalde, Texas, and Buffalo, New York, a bipartisan group of 10 Republican and 10 Democratic U.S. senators reached an agreement on a federal response on June 21.

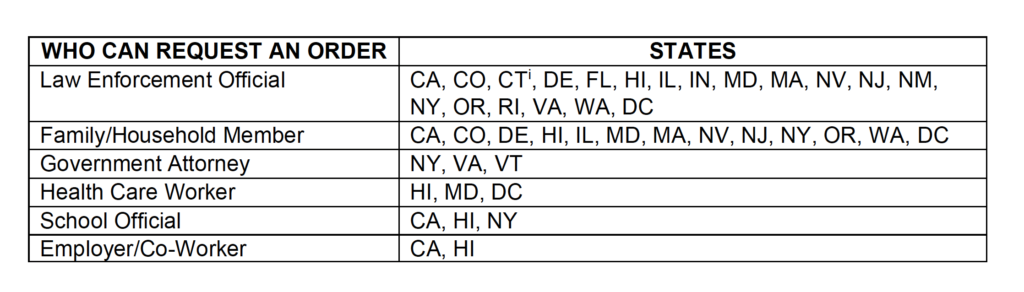

The proposed legislation includes $750 million for crisis intervention programs, including so-called “red flag” (or “extreme risk”) protective orders. Generally, these statutes allow law enforcement officials, household and family members, and others to petition a judge to issue an order removing firearms from an individual’s possession and/or preventing them from making firearm purchases. The processes fluctuate among the states, but all roughly reflect approaches to domestic violence protective orders. Variation occurs in two primary areas: who can request extreme risk protection orders and how long the orders last.

Recent polling indicates there is broad public support for stricter gun laws in general and more specifically for “red flag” laws. Evidence is inconclusive about whether extreme risk protective orders reduce the number of episodes of gun violence, such as mass shootings. But there is anecdotal evidence from California and New York that crises can be avoided with intervention, especially when stakeholders are trained in effective implementation.

Those critical of “red flag” laws raise concern about protecting the due process rights of individuals subject to such orders. The need for due process in this policy space is substantial since it deals with the Second Amendment’s protection of “the right to keep and bear arms.”

While the current conversation has its genesis in mass shootings, evidence also makes clear that the presence of these statutes reduces rates of suicide. Deaths by suicide account for more than half of all firearm-related fatalities in the U.S. Extreme risk protective order laws in Connecticut and Indiana, for example, were found to substantially reduce these fatalities.

Nineteen states and the District of Columbia have these laws in place. Click on the state to review that legislation:

Variation occurs in two primary areas: who can request extreme risk protection orders and how long the orders last.

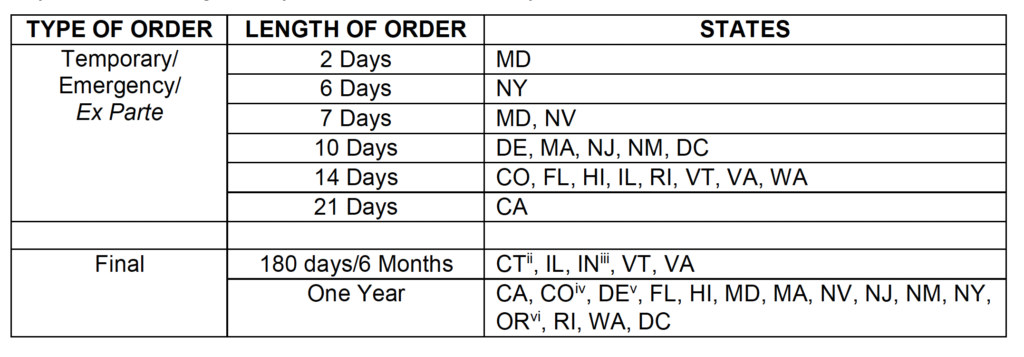

There are two types of orders: temporary (e.g., emergency, ex parte) and final. Temporary orders can be granted without notice to the individual said to be at-risk and last no more than 21 days. Final orders generally last six months to one year.

The parameters of due process of orders with longer time frames are debated. A judge’s ability to issue an order is contingent upon a range of standards, from the most lenient (“reasonable cause” in states like California and Washington) to the most stringent (“clear and convincing evidence” in states like Delaware and Illinois). More detail on the legal standards across states can be found here.

More resources for state policymakers include:

Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions

[i] In Connecticut, family and household members and health care professionals can request an investigation, but only law enforcement has the authority to request a protective order.

[ii] In Connecticut, no end date is specified, but and individual can petition for the removal of the order after 180 days.

[iii] Indiana has two orders: warrant (lasts 180 days after issuance) and warrantless (lasts 180 days after court order).

[iv] In Colorado, the final order is for “364 days”.

[v] In Maryland, only family and household members can petition for a final order.

[vi] In Oregon, only a final order is available.