Across many policy areas, during times of domestic and international instability, nations often turn to their closest allies for reliability and security.

Thankfully for the United States and Canada, they’ve never had to look far.

A case in point: energy policy, especially today amid considerable global uncertainty and changing demands closer to home.

“The U.S. and Canada are essential trade partners in energy,” says Ben Cahill, a senior fellow in the Energy Security and Climate Change Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

“The U.S. is far and away the biggest export market for Canada, and Canada is one of the most critical suppliers to the U.S.”

‘Huge Volume of Crude’

The nature of this energy trade can vary considerably across the two countries’ shared 5,525-mile border.

In the Pacific Northwest, natural gas from the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin is moved to markets on the U.S. side of the border. Between New England and Canada, Cahill says, there is considerable trade in both electricity and fuel products.

In the Midwest, one type of energy trade has tended to dwarf others — the “huge volume of crude that is sent to the U.S. refining system,” Cahill says.

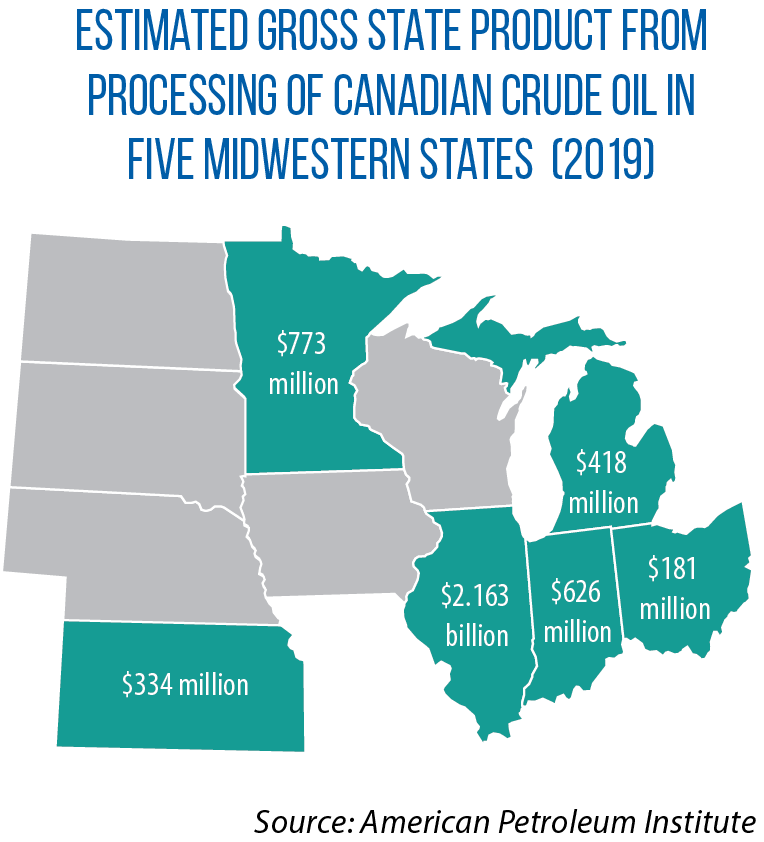

Among all 50 states, for example, Illinois has the largest energy trade relationship with Canada, driven largely by imports of crude oil.

The state, in fact, has the most economic activity in the nation from the processing of Canadian heavy crude oil, according to the American Petroleum Institute.

Alberta, Canada’s leading producer of oil and natural gas, had a $69 billion energy trade market with the United States in 2020.

One benefit of all this cross-border activity has been a strengthening of energy security for both nations; for instance, an increase in Canadian imports is one reason why the United States has been able to decrease oil imports from OPEC countries by 70 percent since 2019.

This energy relationship entails much more than crude oil, though.

Canada and the United States help power each other’s homes and businesses, and at both the federal and state-provincial levels of government, leaders are looking at ways to deepen this part of the relationship.

“Since the U.S. and Canadian grids are integrated in pretty significant ways, I can envision a future where we’ll have much more cross-border electricity trade,” Cahill says.

“So bringing people together at the regional level and national level to talk about this stuff and plan it out will be quite important.”

How Manitoba, Minnesota Connected on Clean Energy

U.S. Secretary of Energy Jennifer Granholm and Canadian Minister of Natural Resources Seamus O’Regan launched a memorandum of understanding in June 2021 that lists 15 cooperative activities to help secure the electric grid and progress toward a goal of net-zero emissions by 2050.

This new cooperative agreement also came with a first-ever analysis of how building international transmission capacity and better integrating the two countries’ renewable energy resources can make North America’s electricity grid cleaner and more resilient.

The U.S. and Canada already share a decent amount of electricity, and of the 57 major transmission lines between the U.S. and Canada, 20 are located in the Midwest.

However, many of these are older transmission lines that connect grids based on fossil fuel sources.

New cross-border transmission lines with improved infrastructure, higher voltages and renewable sources will be necessary in the coming decades as more cars and homes run on electricity.

“We need to build redundancy into our energy systems,” Cahill says. “We need to plan for the worst-case scenarios rather than the best-case scenarios when planning for the energy transition. We can’t assume that the smoothest, most rapid transition away from fossil fuels will happen.”

“That means that we need to build everything. It’s ‘both and,’ not ‘either or.’”

Building newer, clean-energy transmission lines is easier said that done, though. One example from outside the Midwest shows the time that these projects can take and the obstacles they face.

The Champlain Hudson Power Express is a proposed high-voltage line that will connect hydropower and wind energy from Québec to the New York City area.

Beginning in 2010, the project has faced considerable public scrutiny, and having just secured financing and with government permitting still under way, the project seems unlikely to be completed as scheduled by 2025.

But there also are instances of successful, newly completed cross-border transmission line projects.

In the Midwest, Minnesota Power’s 224-mile Great Northern Transmission Line (GNTL) opened in 2020. It crosses northern Minnesota to a point near the town of Roseau. From there, it connects with Manitoba Hydro’s 132-mile Manitoba-Minnesota Transmission Project (MMTP), which begins in Winnipeg.

The GNTL delivers clean hydropower from Manitoba to residential and industrial consumers in northern and central Minnesota.

The line was built as part of Minnesota Power’s larger Great Northern Renewable Energy Initiative, which set a goal of having 50 percent of its electric supply come from renewable sources by 2025.

This initiative also involved the creation of the 500-megawatt Bison Wind Energy Center in North Dakota and the purchase of an existing 465-mile transmission line from North Dakota to Minnesota.

Minnesota Power reached its 50 percent renewable mark for the initiative five years early, in 2020.

The company now aims to deliver 100 percent carbon-free electricity by 2050.

One might think that a northern Minnesota utility does not have the customer base to really contribute to the clean electrification of the economy, but more than half of Minnesota Power’s supply goes to massive industrial customers such as taconite mines and paper mills.

With the GNTL-MMTP connection, cleaner energy from Manitoba is being delivered to these customers.

Why Cross-Border Lines Make Sense in the Midwest

More transmission increases grid reliability, says Daryl Maxwell, Manitoba Hydro’s transmission services and compliance department manager.

“By building more transmission, you provide multiple paths for the energy to travel from the generator to the customer. If one path is constrained, there is an alternative path to deliver the energy to the customer without interruption,” he says.

“So, when you expand your transmission system from a radial system (single path) to a network system (multiple paths) you increase transmission reliability.”

From a generation perspective, Manitoba on average produces more hydropower than it consumes. And when looking to offload this extra electricity, it makes sense for Manitoba Hydro to look to the United States because if there is a large supply of water to produce hydropower in Manitoba, there probably is a large supply in Saskatchewan and northwest Ontario as well.

Likewise, on the demand side, when Manitoba is using less electricity in the summer (there is more Manitoba demand in the winter due to space heating than summer air conditioning), there is often similarly reduced demand to the west and east.

However, electricity demand to the south, in the United States, has traditionally been highest in the summer. When air conditioners are kicking at full speed in Minneapolis in August, Manitoba Hydro can sell and send its excess hydropower to keep things running.

And the trade doesn’t just go from north to south.

“It absolutely flows both ways, and that’s one of the cruxes of this resiliency, a reliability-based infrastructure that is the GNTL,” says Julie Pierce, vice president of strategy and planning for Minnesota Power.

“It allows us to optimize the systems and the renewable clean energy prevalent in the United States and Manitoba.”

By combining North Dakota wind power and Manitoba hydropower, the project has helped create a grid that can rely on once source of carbon-free energy when conditions do not allow for the other to operate efficiently.

“It was very important during the [2021 Manitoba] drought that the line could flow energy to the north,” Pierce says. “And during Winter Storm Uri, it was really important that the line was in service as that power flowed south and helped the upper Midwest.”

In this way, the GNTL-MMTP connection essentially acts as a battery. When wind power is abundant in the United States, Manitoba Hydro can pool its water (partly using wind energy to hold the water behind the turbines).

When wind power is lacking or when demand peaks, Manitoba Hydro can release more water and increase its hydropower output heading south.

While the Manitoba-Minnesota project is now operating efficiently and effectively, getting to this point was not easy. From the start of planning in 2012 to completion, the project took about eight years.

A certificate of need was required from the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission; it was granted in 2015. The commission also had to approve a route permit. That occurred in 2016, the same year that the U.S. Department of Energy issued a presidential permit, which was required to connect to Manitoba Hydro’s system at the U.S.-Canadian border.

Finally, right-of-way permissions were needed from several local governments along the 224-mile transmission lines, including the sovereign Red Lake Band of Chippewa Indians.

Along the way, too, utilities had to secure what Maxwell calls the “social license” — acceptance of the transmission line from various stakeholders concerned about it. Without proper engagement, he says, projects can often fail on regulatory licensing because of opposition from stakeholders.

This is where legislators and other policymakers on both sides of the border can make a big difference.

“Bring the people together to create greater acceptance [of these cross-border energy projects],” Maxwell says. “I think the role for government is to provide that leadership.”

Additionally, as electricity demand and the need to integrate clean energy grows, completing new international and inter-regional transmission lines in a timely manner becomes essential.

“It took us over 10 years to bring this line to fruition,” Pierce says.

“If we want to meet the goals that we have between our two nations and for North American more broadly, and even the globe, we’re going to need to get better at process and streamlining that ability to build infrastructure through thoughtful coordination and reform.”

The post Long a Hallmark of the U.S.-Canada Relationship, Binational Energy Trade Has Room To Grow Further appeared first on CSG Midwest.