In most states, the introduction of a bill does not ensure that it will receive a formal hearing or vote. Instead, some discretion on what legislation gets considered often is left to legislative leadership, a special rules or assignments committee (typically composed of top caucus leaders and controlled by the majority party), and/or the chair of the standing committee that has been assigned the bill. However, there are exceptions.

For example, under the rules of the North Dakota House and Senate: “Every bill and resolution referred to committee must be scheduled for a hearing in committee, and a hearing must be held on the bill or resolution before the appropriate deadline for reporting the bill or resolution back to the [full chamber].”

For example, under the rules of the North Dakota House and Senate: “Every bill and resolution referred to committee must be scheduled for a hearing in committee, and a hearing must be held on the bill or resolution before the appropriate deadline for reporting the bill or resolution back to the [full chamber].”

Through a vote of its members, the relevant standing legislative committee in North Dakota recommends a “do pass” or “do not pass” on each bill. Regardless of that vote, though, every measure reaches the floor of the legislative chamber from which it originated. The result: All House or Senate members in North Dakota have the chance to vote on, and decide the fate of, every bill introduced in their respective chamber.

Under the rules of the Nebraska Unicameral Legislature, all bills and resolutions (with the exception of some technical legislation) must receive a public hearing from the relevant standing committee. Unlike in North Dakota, a Nebraska standing committee can vote to indefinitely postpone, or kill, a bill.

Rules in some states allow members of the legislature to get a bill withdrawn from a committee (after a certain period of inaction) and placed on the legislative calendar. The number of votes required for such a move varies from state to state. In South Dakota, if one-third of the members of a chamber vote to “smoke out” a bill that stalled in committee, the measure is sent to the floor for a vote by the full House or Senate.

Limits on bill introductions

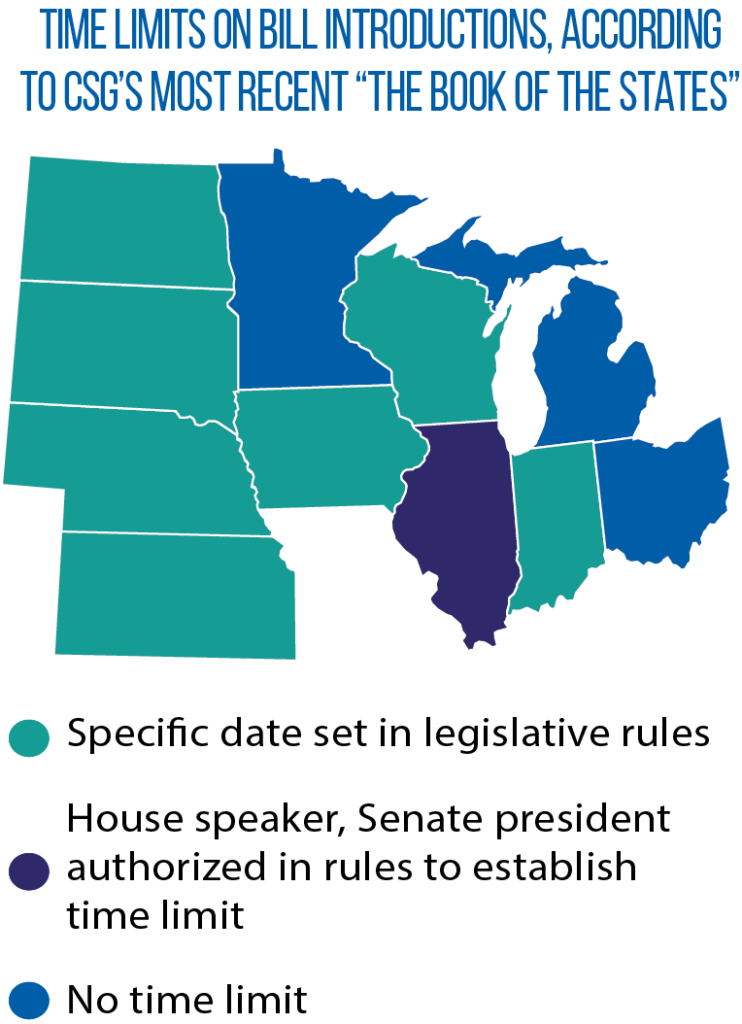

Another variance among states: the number of bills being introduced during legislative session. In 2020, that number exceeded 9,000 in Illinois and Minnesota, compared to fewer than 500 in South Dakota. According to The Council of State Governments’ most recent “The Book of the States,” seven states in this region limit when bills can be introduced, either via rules adopted by the full legislative body or dates set by leadership (see map).

Another variance among states: the number of bills being introduced during legislative session. In 2020, that number exceeded 9,000 in Illinois and Minnesota, compared to fewer than 500 in South Dakota. According to The Council of State Governments’ most recent “The Book of the States,” seven states in this region limit when bills can be introduced, either via rules adopted by the full legislative body or dates set by leadership (see map).

Legislation in Nebraska must be introduced by the end of the 10th day of session. After the 12th day of a 40-day session in South Dakota, members are limited to being the prime sponsor of three bills; they cannot introduce any legislation after the 15th day. Likewise, North Dakota stops the introduction of bills after the 13th day of session, and after the eighth day, members only can serve as the primary sponsor of up to three bills.

The Indiana House and Senate cap how many pieces of legislation that individual members can introduce: in the House, no more than 10 bills in odd-numbered session years and no more than five in even-numbered years; and in the Senate, no more than 15 bills or resolutions in odd-numbered session years and no more than 10 in even-numbered years.

Capital Closeup is an ongoing series of articles focusing on institutional issues in state governments and legislatures.

The post Capital Closeup: Do any Midwestern states require that all bills receive a legislative hearing and/or vote? appeared first on CSG Midwest.

In 2022, Iowa lawmakers approved a sweeping measure (

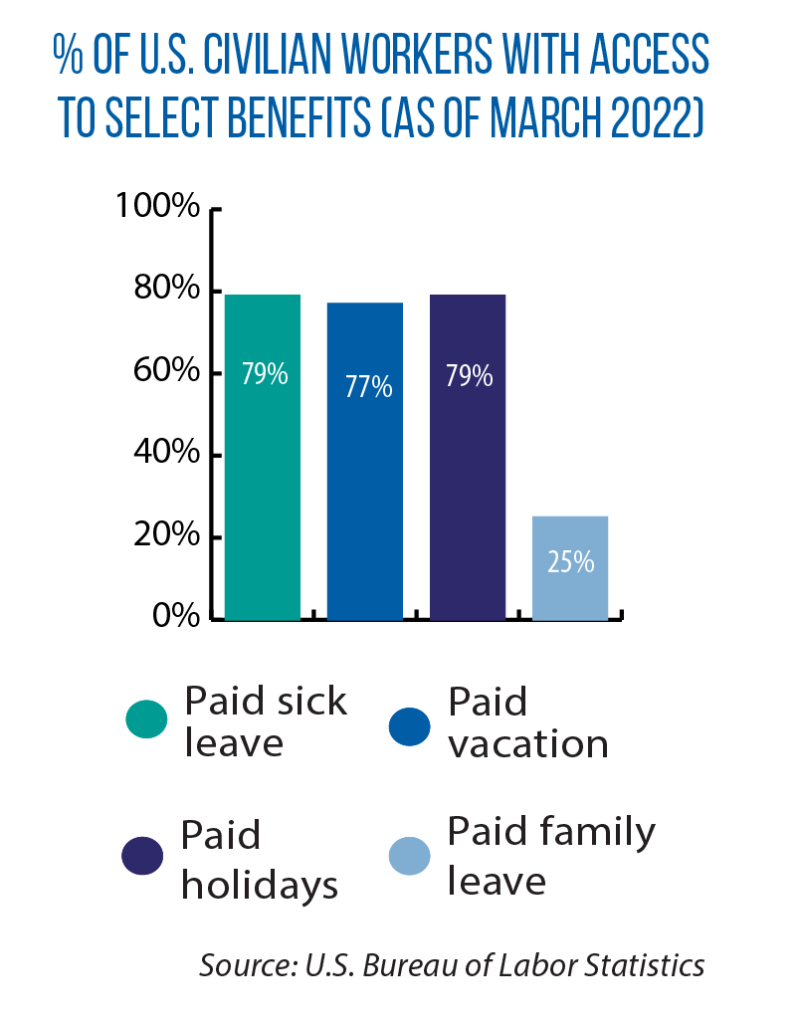

In 2022, Iowa lawmakers approved a sweeping measure ( In recent years, a more common state action has been to guarantee access to paid family and medical leave. According to a recent

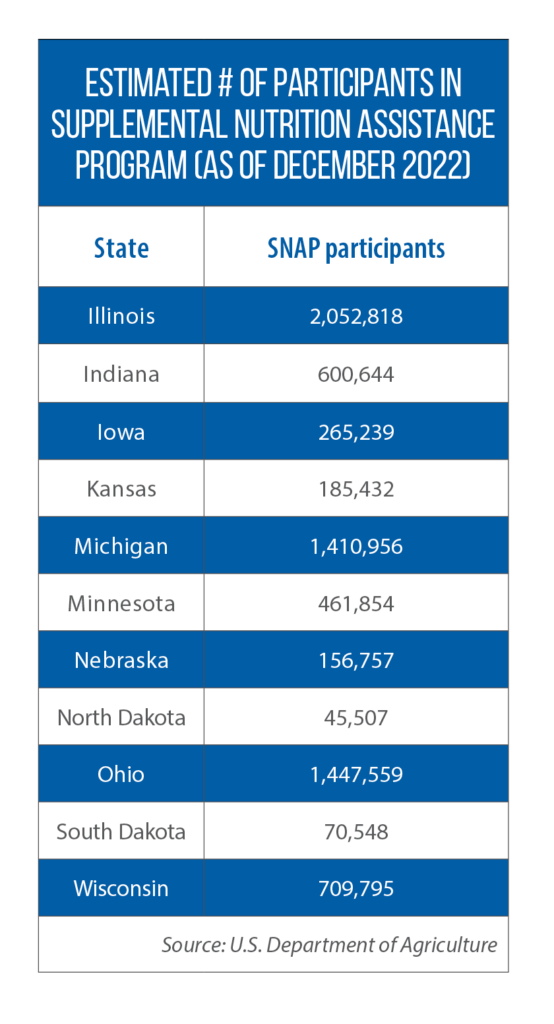

In recent years, a more common state action has been to guarantee access to paid family and medical leave. According to a recent  With both initiatives, the idea was to boost the food-purchasing power of lower-income people getting assistance via the federal

With both initiatives, the idea was to boost the food-purchasing power of lower-income people getting assistance via the federal  In Minnesota, for example, Market Bucks was available in 105 different farmers markets last year, says Jill Westfall, director of programs for Hunger Solutions Minnesota.

In Minnesota, for example, Market Bucks was available in 105 different farmers markets last year, says Jill Westfall, director of programs for Hunger Solutions Minnesota. Demand for the program has never been higher, and it’s one reason why Sen. Maye Quade and other legislators want a funding boost in Minnesota’s new biennial budget. She has proposed an annual appropriation of $500,000, up from the existing $325,000 (SF 1927). Right now, Market Bucks is only available at farmers markets. Under Maye Quade’s bill, two other options would be added: one, direct sales from farmers; and two, sales based on a “community supported agriculture model,” in which individuals purchase subscriptions, or shares, of food produced from a local farm in advance of the growing season.

Demand for the program has never been higher, and it’s one reason why Sen. Maye Quade and other legislators want a funding boost in Minnesota’s new biennial budget. She has proposed an annual appropriation of $500,000, up from the existing $325,000 (SF 1927). Right now, Market Bucks is only available at farmers markets. Under Maye Quade’s bill, two other options would be added: one, direct sales from farmers; and two, sales based on a “community supported agriculture model,” in which individuals purchase subscriptions, or shares, of food produced from a local farm in advance of the growing season.