Increased funding, innovative strategies intend to offer resolve

By Cody Porter and Jennifer Horton

Homelessness in the United States trended upward ahead of the COVID-19 pandemic. An already dire situation neared critical levels as the economic downturn forced countless businesses to close and unemployment rates to surge.

The nationwide poverty rate in 2020 climbed by 3.3 million, increasing the total number of individuals living in poverty to 37.2 million people, or 11.4% of the population. With necessities like housing being less affordable due to soaring home prices, homeless numbers also grew.

As of January 2022, an estimated 582,462 individuals experienced homelessness in the U.S., according to the National Alliance to End Homelessness. Rates of homelessness vary widely across the states. Per capita, Washington, D.C., California, Vermont, Oregon and Hawaii have the highest rates of homelessness.

State legislators take a range of approaches to address the nuances linked to homelessness, including efforts focused around affordable housing, transitional housing, and programs like Housing First that reduce prerequisites involved in the buying or renting processes.

— Wayne Niederhauser, Utah homeless coordinator

Utah Gov. Spencer Cox appointed former Senate President Wayne Niederhauser to the role of state homeless coordinator in April 2021. His appointment came on the heels of the Utah Legislature establishing the role in its pursuit of a strategic plan to reduce homelessness.

That strategic plan — the Statewide Collaboration for Change: Utah’s Plan to Address Homelessness — arrived in March, a year after the Utah Department of Workforce Services revealed a 14% increase in the number of Utahns experiencing first-time homelessness. Response efforts included within the plan include a five-goal strategy centered around increasing opportunities for accessible and affordable permanent housing, support services and case management, homeless prevention strategies, and housing resources and services for the unsheltered.

In September 2022, Salt Lake County, Utah, received $30.2 million from the state for new affordable housing. The funds were part of a broader $55 million statewide investment via American Rescue Plan Act funding for the construction of 1,078 affordable to deeply affordable housing units. Access to deeply affordable housing is for those who annually earn less than $25,000.

“We now have the opportunity to increase deeply affordable housing, which is the hardest housing to provide,” Niederhauser said. “That’s focused on homelessness and workers who really are [earning] $15-20 per hour and got to have deeply affordable housing.”

Salt Lake City’s 40-acre Other Side Village is among the first developments to come from the ARPA funding in 2022. Ground broke in March for the tiny home village, which is expected to house 60 individuals experiencing homelessness. The plan is to further develop the lot to offer sufficient housing for as many as 400 individuals.

“Deeply affordable housing requires additional help — [more than just] low-income housing tax credits,” Niederauer said. “The project needs to be sustainable and it’s not sustainable if it doesn’t have enough cash flow.”

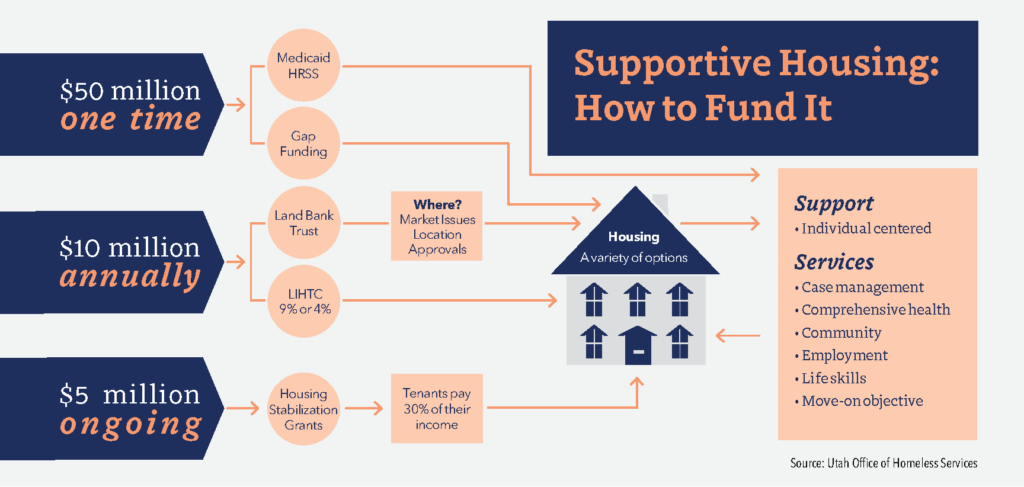

In total, more than $200 million was appropriated by the Utah Legislature for affordable housing and homelessness initiatives prior to concluding the 2023 session. According to Niederhauser, legislative successes include $50 million in deeply affordable housing funding; a low-income housing tax credit worth nearly $60 million; housing stabilization grants, including project based rent support, accompanied by $5 million in funding; a statewide code blue system; a request for a response plan for larger counties; and $12 million for homeless services.

Between 2005-15, Utah was a prime example of how to curb homelessness through its use of the Housing First model. The state reported reducing its homeless population by 91% throughout the decade, although that number has decreased since 2015.

Housing First is an evidence-based approach to ending homelessness that provides people with immediate access to housing and support services without preconditions. Based on the belief that people need to have their basic needs met before addressing other issues like employment or substance abuse, the Housing First model emphasizes client self-determination within a trauma-informed, harm-reduction framework. The model has been successful when applied to a range of circumstances, including both families who became homeless due to a temporary crisis and chronically homeless individuals.

There are two common models that utilize the Housing First approach depending on a person’s needs and whether they need long or short-term assistance. The permanent supportive housing model provides long-term rental assistance and supportive services to individuals with chronic illnesses, disabilities, mental health issues or substance use disorder who have experienced long-term or repeated homelessness. A second model, known as rapid re-housing, provides short-term rental assistance and services to help people obtain housing quickly and increase self-sufficiency so they can remain housed.

The Maine Legislature’s Committee on Housing hosted Niederhauser in March to learn more about Utah’s successes and failures with the Housing First model.

“I testified in their committee because they wanted to know what happened in Utah. The fact is we didn’t keep up. That’s the bottom line,” Niederhauser said. “You need to provide housing, but you also need to provide more as your population grows … and you have got to have deeply affordable housing to address homelessness. You can’t be satisfied with what you’ve done in the past. It has to be an ongoing effort.”

Maine ranked eighth per capita for homelessness in 2022, according to data compiled by the National Alliance to End Homelessness. And from 2021-22, Maine’s homeless population increased by 113.8%, according to U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

“[Housing First] is an initiative that really is transformational,” said Ryan Fecteau, senior advisor of community development and strategic initiatives for the Maine Governor’s Office of Policy Innovation and the Future. “It’s probably the most transformational policy around homelessness in Maine history and will be a huge step forward in addressing that.”

Housing First was included in by the recently proposed budget of by Maine Gov. Janet Mills. If adopted, the program, contained in Speaker Talbot Ross’ proposed LD 2, would be established within the Maine Department of Health and Human Service.

An estimated 450 chronically homeless Mainers currently live throughout three Housing First model properties in Portland. Ninety efficiency apartments were constructed by nonprofits Avesta Housing and Preble Street in 2005, 2010 and 2017.

“Our service center communities, particularly Bangor and Portland — our two largest cities — are shouldering this challenge in a big way because a lot of people seek services in the city,” Fecteau said. “[While those seeking shelter] might not necessarily be from Portland or from Bangor, they end up there as a means of seeking services from the cities. Getting people stabilized affordable housing is a challenge across the spectrum. Whether it be folks who are experiencing homelessness or folks who are currently housed, they are having to pay way more than they should have to with their annual incomes.”

Fecteau added that Gov. Mills’ proposed budget also offers $12 million in one-time funds for the Emergency Housing Relief Fund. Those funds could continue supporting efforts to assist individuals and families experiencing homelessness. In addition, the Legislature included a $21 million emergency spending package in January supporting emergency housing and shelter.

Research indicates people assisted through the Housing First model access housing faster and are more likely to remain housed, with studies showing a one-year housing retention rate ranging from 75-98%. The approach tends to be cost-efficient, generating savings through reduced usage of emergency services, hospitals, jails and emergency shelters.