By Sean Slone, Senior Policy Analyst

CSG Senior Policy Analyst Sean Slone traveled to Japan in February as a delegate to this year’s Local Government Exchange and Cooperation Seminar hosted by the Council of Local Authorities for International Relations (CLAIR).

Each year, CLAIR invites a group of senior state and local government officials and staff from the organizations that serve them to experience Japan firsthand and engage in enlightening information exchanges and networking. The Japan Local Government Centre, CLAIR’s U.S. office in New York City, is a longtime partner of CSG and other state and local government organizations. Slone was chosen by CSG leadership to participate based on his long tenure at CSG.

This year’s delegation included a mayor from Washington, a state senator from Hawaii and representatives of the International City/County Management Association, National Association of Counties, National Conference of State Legislatures, Sister Cities International, and the Association of Municipal Managers, Clerks and Treasurers of Ontario. The group spent time in Tokyo learning about the local government system before riding the bullet train to Okayama Prefecture for a regional study tour in the southern part of Honshu Island on the Seto Inland Sea.

The United States has a lot riding on the success of Japan. For one thing, the country is a major market for U.S. goods and services, including agricultural products, commercial aircraft and pharmaceuticals.

Moreover, in 2022, Japanese automakers manufactured about 2.82 million vehicles at production facilities in the United States, supporting more than 2.3 million U.S. jobs. Those automobile manufacturers play an essential role in the U.S. economy having invested more than $60 billion in manufacturing facilities over the past 40 years.

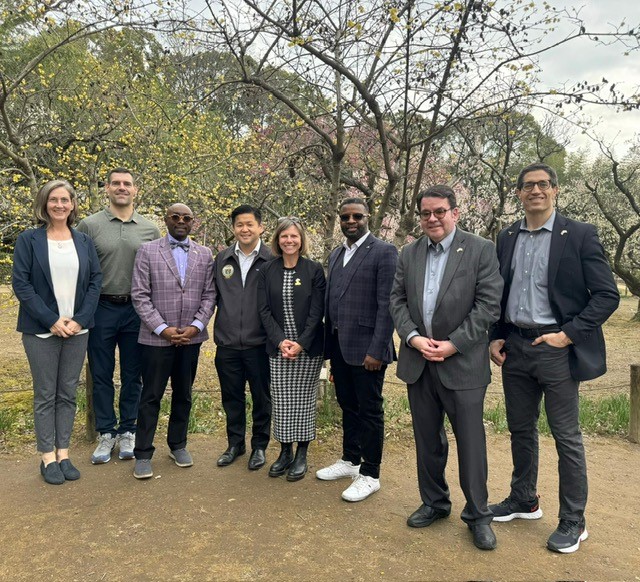

Photo: CSG Senior Policy Analyst Sean Slone (second from right) poses for a photo alongside his CLAIR Fellowship Exchange Program attendees at the Korakuen Garden in Okayama on Feb. 15. Photo credit: Natalie O’Donnell Wood, National Conference of State Legislatures.

Located near the CSG national headquarters in Lexington, Kentucky, is the community Georgetown, which has benefited considerably from the presence of one of those manufacturers: Toyota Motor Manufacturing. Toyota set up shop in 1986 and now employs more than 9,300 individuals. By one estimate from a few years ago, if indirect jobs and spin-off companies are factored in, the number of jobs supported statewide is closer to 30,000.

State policymakers around the country recognize that maintaining the economic impact of a company like Toyota requires building and maintaining an educated workforce. But in recent years, that is where the United States has struggled, for several reasons. It’s estimated that the U.S. has lost as many as 1.4 million workers from the labor force since the start of the pandemic in February 2020. Meanwhile, the birth rate in the U.S. has decreased since the Great Recession, declining almost 23% between 2007 and 2022. Whereas in 1950, the average American woman gave birth to three children, today that number is around 1.6, significantly below the replacement rate of 2.1 children needed to sustain a stable population.

Photo credit: Commissioner Larry Johnson, DeKalb County, GA

Photo credit: Sean Slone

Photo credit: Sean Slone

While we may not talk much about such declines in the United States, Japanese government officials are very concerned about how a declining population and birth rate on the island nation may impact their future. It was a concern expressed by many of the officials the CLAIR delegation met with in February. However, that concern may ring slightly hollow as you’re wandering the busy streets of Tokyo’s Shinjuku neighborhood on a weekend night, making your way through a busy train station to catch the shinkansen — Japan’s smooth-running bullet train — or jostling with hundreds of other tourists for the best view at Tokyo Skytree, the 2,000-foot-high broadcasting and observation tower that affords a commanding sense of the scope of the world’s most populous city.

Still, government officials predict that most Japanese prefectures will see significant declines in population between now and 2050. Eleven prefectures will each see their population shrink by more than 30%, according to the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research. Moreover, the Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry reported that the number of babies born in 2021 fell by nearly 30,000 from the previous year. At the same time, the number of people age 65 or older in Japan reached a record high of 36.27 million in 2022.

The reason for the concern in Japan is that the regions expected to experience the biggest population declines are likely to face declining tax revenues and economic contraction, making it difficult to maintain infrastructure and local government services. And while Tokyo is expected to remain hugely popular both with Japanese and transplants from elsewhere — its population is expected to increase 2.5% over the same period — many believe the concentration of people in the city is a matter of some urgency.

Shunsuke Kimura, a professor in the Graduate School of Governance Studies at Tokyo’s Meiji University, told CLAIR seminar delegates the nation’s long-term vision for taking action against a shrinking society includes four objectives:

- Generating stable employment in regional areas.

- Creating a new inflow of people into regional areas.

- Fulfilling the hopes of the young generation for marriage, childbirth and parenthood.

- Creating regional areas suited to the times with safe and secure living and cooperation with other regions of the country.

One factor that many believe could help lift Japan’s outlying regions — and one that U.S. communities might want to take some cues from — is a focus on education that emphasizes both civic engagement at home and study abroad programs that allow students to experience other parts of the world.

Photo credit: Commissioner Larry Johnson, DeKalb County, GA

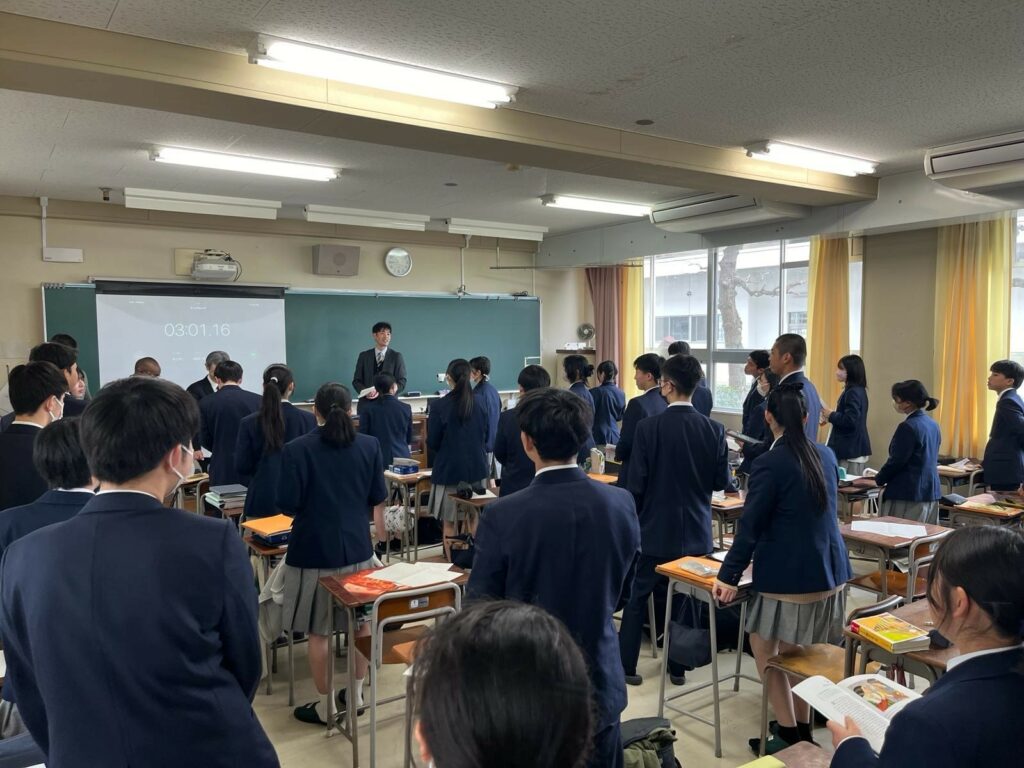

“Romeo and Juliet” at Joto High School.

Photo credit: Mayor Mary Lou Pauly, Issaquah, WA

During a visit to Okayama Prefecture, CLAIR delegates had the opportunity to visit Joto High School and hear about the school’s system for “raising global leaders.” School officials detailed characteristics they aim for in their students, including both support for the local community and a global mindset. They said they seek to nurture creative and critical thinking as well as an ability to use advanced English. The school emphasizes three initiatives, including studying community issues, deepening cultural exchange, and fostering independence and autonomy. As part of a three-year program, students learn cross-curriculum research skills, visit local companies to learn about global issues, conduct empirical research with an emphasis on regional fieldwork, and in year three, do personalized, in-depth research and thesis writing in both English and Japanese, while focusing on four courses: humanities and social sciences, international studies, science and math, and music.

In one classroom at Joto, delegates observed students studying and discussing a simplified version of Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet” in English (it was the week of Valentine’s Day). In another classroom, students were invited up front to play back elaborate musical compositions they had composed. Down the hall, others were conducting experiments with beakers and Bunsen burners.

Perhaps most impressive was a presentation from a young girl titled “Visualizing Abstract Japanese Aesthetics.” It was a highly conceptual, multi-disciplinary exploration of complex themes such as the core concept to Japanese aesthetics of “wabi-sabi” — the notion that beauty and enjoyment can be found within the deterioration of worldly things. Or as the young student put it, “beauty in decay.”

Joto students also can experience numerous international exchanges, including long-term or short-term study abroad programs in Australia, Canada and the United States.

Student exchange is also a focus at Okayama Prefectural University, the 30-year-old higher education institution in the city of Soja that was also on the delegation’s travel itinerary. University officials there highlighted global partner universities and international networks across North America, Europe, Asia, Oceania and Africa. The university serves a student body of just over 1,700 studying in areas like health and welfare science, computer engineering and design. One student detailed her year of study in Toronto at the University of Guelph, where she created a club for fellow students on making vegetarian Japanese food.

The international focus highlighted across Okayama seemed to reflect the life experience of Ryūta Ibaragi, the prefecture’s dynamic and long-serving governor, who in 1995 received a Master of Business Administration from the Stanford University Graduate School of Business. The governor, whom delegates got the chance to meet and exchange gifts with, has established as one of his priority initiatives reclaiming Okayama’s status as the “Education Prefecture.”

Photo: Ryūta Ibaragi, governor of Okayama Prefecture, speaks to members of the CLAIR delegation at the Okayama Prefectural Office on Feb. 14. Photo credit: Sean Slone.

While education may be a key to the future of many places in Japan as the country tries to reverse course on its shrinking society, another concern has emerged more recently in the island nation: a shrinking economy. Last year, Japan lost its spot as the world’s third-largest economy, contracting in the fourth quarter of 2023 and slipping into recession as it fell behind Germany.

But there aren’t many countries in the world where recession would look quite like this. There is commerce everywhere in Japan. From the high-end retailers at every multi-story department store in Tokyo to the businesses clustered around Japan’s train stations to the ubiquitous convenience stores where you can get a surprisingly decent late-night snack and cook and eat it on-site. Wandering the well-stocked aisles of the enormous Don Quijote discount store in Shinjuku, it begs the question: Who is buying all this stuff? Isn’t there a recession going on?

One place providing respite from the non-stop commerce is the peaceful Okayama Korakuen Garden, a 300-year-old Japanese garden that is considered one of the nation’s three great gardens. Unlike one of the gardens of Europe, where the goal is to keep things looking much as they did in the time of long-dead monarchs, Korakuen will not be the same 50 or 100 years from now, we were told. It is designed in the “scenic promenade” style, which presents the visitor with a new vista from every path or tea house on the property. And as an Italian guide told the delegation, the garden is a “moment in time.” It is a memento mori — a reminder of impermanence and the inevitability of death, a reminder of the beauty in decay. Like the cherry blossom — Japan’s enduring symbol of beauty and mortality — it is ephemeral, here one day and gone the next.

As the group prepared to leave Okayama Prefecture and return to Tokyo, delegates were invited to give their impressions of the trip. One of our fellow travelers suggested he needed a couple more days to experience Japan. I told the CLAIR and prefectural staff I needed a couple more lifetimes. But I get the feeling that if I were to return to Japan every year and immerse myself in the country, it would be difficult to ever truly know Japan. Like the garden, the country is a moment in time. A remarkable, unknowable place where past and present collide, and where its residents are trying to shape a bright future despite ominous headwinds.