Every year, about three million shipments of radioactive materials occur across the United States.

Trucks and trains carry low-level radioactive waste from hospitals or universities, transuranic waste from U.S. defense facilities, and uranium to nuclear power plants.

However, one type of radioactive material tends to receive the most public attention — spent nuclear fuel.

This attention may be due to the higher levels of radioactivity in spent nuclear fuel, or because it has been part of a decades-long, and still unresolved, challenge of what do to with the radioactive waste produced by the nation’s nuclear power plants.

Without a single, permanent national repository, or a few larger interim storage sites, the spent fuel from these plants largely remains unshipped and on-site — and will stay at these locations until a solution to the storage problem arises.

For these reasons, shipments of spent nuclear fuel have sometimes taken on an almost mythical, impossible quality.

Yet one organization has been transporting spent nuclear fuel across the country without incident for more than 65 years.

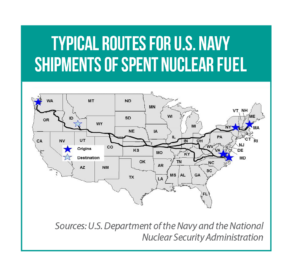

Since 1957, the U.S. Navy has completed almost 1,000 shipments from various ports to the Idaho National Laboratory, via routes that run through parts of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, Kansas, and Nebraska in the Midwest.

High Radioactivity, High Levels of Safety

Used in 11 aircraft carriers and 67 submarines in the U.S. Navy’s fleet, nuclear power allows for stealthy, high-speed travel. For example, the USS Missouri recently completed a seven-month deployment in which it covered 40,000 nautical miles and was at sea 90 percent of the time, all without the need to refuel.

When these ships’ nuclear reactors are refueled or defueled, the spent fuel needs to be transported for inspection in Idaho. It is shipped in one of two kinds of shipping containers, both of which meet or exceed federal safety requirements.

Computer modeling and scale model testing has shown that these containers can withstand a 30-foot drop onto an unyielding surface and a 40-inch drop onto a metal rod, or being engulfed by a 1,475 degrees Fahrenheit fire for 30 minutes or immersed in 50 feet of water. Additionally, the fuel itself is durable, having been designed to withstand intense battle shock.

And there is another layer of safety for these radioactive waste shipments: accident demonstration exercises led by the U.S. Navy and held along a shipping route.

These recurring exercises have taken place in locations throughout the country, including Topeka, Kan., and Fort Wayne, Ind.

Various scenarios are used to model an accident during shipment; then, first responders simulate their actions to assess, respond to, and secure the accident scene.

Most recently, the Naval Nuclear Propulsion Program held an accident demonstration exercise in the Missouri town of Moberly; several members of The Council of State Governments’ Midwestern Radioactive Materials Transportation Committee were on hand to watch and take part in the September event.

In this particular demonstration scenario, a shipment was traveling via rail from Virginia to Idaho.

A utility boom truck was approaching an intersection in Moberly and failed to stop in time, resulting in the overhead boom equipment hitting the shipping container. The truck remained upright but began leaking hydraulic fluid, while several heat dissipation fins on the shipping container were bent and the back wheels of the railcar derailed.

Armed shipment couriers traveling in the rail escort vehicle behind the container, along with the train crew traveling in the locomotive in front of the container, took immediate action to ensure the well-being of the boom truck driver. They also established a safety zone around the container of spent nuclear fuel.

Then, local fire and police departments came to assist with the emergency response. State-level organizations began arriving, too, such as the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services to monitor radiation levels coming off the shipping container. The Moberly police chief served as the main public information officer.

Through the accident demonstration, says Ryan Seabaugh of the Missouri Department of Natural Resources, participants were able to gain “a greater understanding of the importance of an need for effective communication among different organizations, in addition to clearly understanding the roles that each organization plays in this type of emergency response.”

For the exercise, Seabaugh, a member of CSG’s Midwestern Radioactive Materials Transportation Committee, coordinated with other state agencies while also providing feedback on the accident scenario and first-responder response.

There are several goals for these kinds of exercises.

First, they provide an opportunity to conduct regional outreach with host communities and states. Additionally, local emergency service personnel and interested political leaders are able to familiarize themselves with naval shipments and interact with shipment couriers. Finally, these demonstrations serve as training opportunities for personnel to practice emergency actions.

Building Trust in Shipments

While U.S. Navy shipments have some unique aspects to them, seeing the containers in person and watching a well-organized response to unlikely accident scenarios can raise public confidence in radioactive materials shipments of all kinds.

Such trust will be needed if or when a permanent repository is found to store spent nuclear fuel from the nation’s power plants. For this highly radioactive waste to reach a national repository, shipments will need to go through many communities of the Midwest, a region home to more than 30 operating or decommissioned nuclear power reactors.

“Seeing the demonstration validated my belief that regardless of a person’s view on nuclear power, we can safely transport [commercial spent nuclear fuel] to a centralized repository,” says Minnesota Rep. Pat Garofalo, another member of the CSG interstate committee.

About the Council of State Governments’ Midwestern Radioactive Materials Transportation Committee (MRMTC)

Formed in 1989, and with members from 12 Midwestern states, the MRMTC identifies and resolves regional issues related to the transport of radioactive waste and materials.

The committee mostly focuses on U.S. Department of Energy shipments and works closely with several offices within the agency. However, when related events or trainings are held by other organizations, such as the recent demonstration exercise in Missouri, the committee is able to send interested members to attend and learn.

Each state is represented on the MRMTC by a gubernatorial appointee from a relevant agency. Legislators on the committee are appointed by the chair of CSG’s Midwestern Legislative Conference.

“Being a newcomer in my current role [in state government], the MRMTC has been invaluable in connecting me with resources, other states with diverse perspectives and experiences, and helping me stay updated on current or future events that could have relevance to Missouri,” says Ryan Seabaugh, a committee member who works at the Missouri Department of Natural Resources.

“Given the highly specialized nature of radioactive materials, we simply do not have access to these resources in individual state legislatures,” says Minnesota Rep. Pat Garofalo, a member of the committee.

“The MRMTC gives legislators access to this important information to help guide public policy decision.”

Five other legislators serve with Garofalo on the committee: Kansas Rep. Mark Schreiber, Nebraska Sen. Suzanne Geist, Minnesota Sen. Mike Goggin, and North Dakota Rep. Dan Ruby and Sen. Dale Patten.