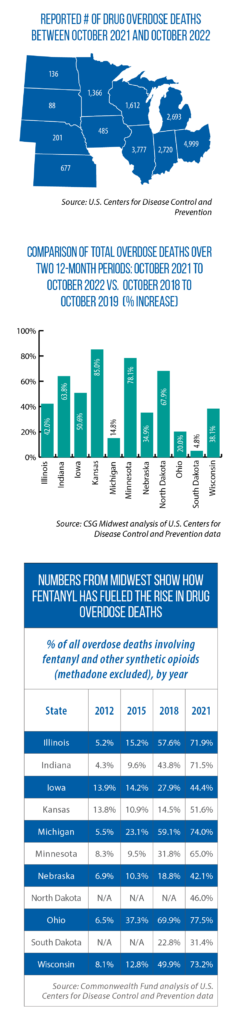

In less than a decade’s time, the number of drug overdose deaths in the United States more than doubled, reaching nearly 107,000 by 2021.

One of the striking aspects of this increase: the role of fentanyl and other synthetic opioids. They were involved in close to 70 percent of all deaths in 2021, compared to only 6 percent of the deaths nine years earlier, according to a recent Commonwealth Fund analysis of federal mortality data.

Anne Milgram, head of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, has said that fentanyl “is the single deadliest drug threat our nation has ever encountered.” This threat has received considerable attention in the Midwest’s state legislatures, with many of the new proposals taking one of two approaches — and sometimes incorporating a mix of both.

The first approach is “harm reduction”: change a state’s laws or invest in new programs that prevent overdoses by reaching and helping people who use drugs. A second strategy is to increase criminal penalties for individuals who manufacture or distribute fentanyl.

‘Numbers are startling’

‘Numbers are startling’

An enhancement of criminal penalties is part of North Dakota’s SB 2248, a bill introduced by Senate Majority Leader David Hogue in early 2023. The measure also requires state-level reporting on fentanyl-related deaths as well as spending $1.5 million from the opioid settlement fund on a public awareness campaign.

“We’re now losing more people to overdose deaths than to motor vehicle fatalities,” Hogue says. “The numbers are just startling.”

Hogue’s hometown of Minot is one of the many communities that has been impacted. A college student there died in early 2023 when he took a drug that he thought would help him study; the drug was laced with fentanyl.

For deadly cases like this, whether they involve fentanyl or other drugs, SB 2248 spells out a stronger criminal penalty — a class A felony for any individual who “willfully delivers a controlled substance, or supplies another to deliver or consume a controlled substance.” Hogue says that language (particularly “supplies another”) reflects changes made to the bill since its introduction — a shift away from punishing lower-level dealers and instead trying to reach “intermediate and upper-echelon dealers.”

The measure also expands venue options for prosecutors. Filing charges in the county where an overdose death or injury occurred is one possibility, but another is for the venue of the offense to be based on where the drug was “directly or indirectly obtained.”

“That way, we can reach those upper-echelon dealers wherever they are,” including outside of North Dakota’s borders, Hogue says.

Another amendment to the bill ensures that individuals adhering to North Dakota’s Good Samaritan law are exempt from the new penalties. That law, a type of harm-reduction strategy in place in many states, provides immunity from prosecution for individuals who seek medical assistance for another person experiencing a drug overdose.

‘Change attitudes’

Last year in Wisconsin, legislators passed a pair of bills, one on harm reduction and the other related to criminal penalties. Wisconsin’s change in criminal code, SB 352, makes the penalties for manufacturing, distributing or delivering fentanyl as severe as those for heroin trafficking. A bill introduced this year, SB 101, would increase the penalty for supplying fentanyl or other drugs that lead to a person’s death, making it a Class B felony punishable by up to 60 years in prison. It is a Class C felony under the state’s current drug-induced homicide law.

The harm-reduction measure from 2022, SB 600, carves out an exception to Wisconsin’s general ban on the possession of drug checking equipment. Under the new law, the use of fentanyl testing strips — a type of drug checking equipment that shows whether a substance has fentanyl in it — was decriminalized.

“We had to change people’s attitudes and minds, because there was a thought that the fentanyl strips would be utilized by the dealers, so some folks didn’t want to decriminalize,” Sen. Van Wanggaard says. “But the bottom line is we don’t want somebody to make a mistake and die from it.”

Decriminalizing the fentanyl strips improves access to them, he says, and can save lives.

According to the Network for Public Health Law, as of the summer of 2022, most Midwestern states did not permit the possession of drug checking equipment, with the lone exceptions being Michigan and Nebraska. Wisconsin and Minnesota, though, did make exceptions for fentanyl testing strips, and Ohio joined these two states with the signing of SB 288 in early 2023.

Other measures to decriminalize the possession and use of fentanyl testing strips appeared likely to pass in multiple states this year.

“Where I think those laws can help is by allowing health departments, hospitals and other organizations to move forward with distributing [the strips],” says Corey Davis, the network’s deputy director.

This harm-reduction policy aims to prevent fentanyl-related overdoses; other policies are broader in scope.

For example, states have varying laws to expand access to naloxone, a drug that reverses an overdose from fentanyl or other opioids.

“Every state has done at least an OK job of trying to increase pharmacy [based] access to naloxone, so you can walk into a pharmacy without first having gone to a doctor and gotten a prescription,” Davis says. “Where it seems like there’s more variation is in permitting, encouraging or funding community groups to give out naloxone — whether that’s part of needle exchange programs, if the state has them, or through homeless shelters, health departments, or any other non-pharmacy places.

“Some states aggressively pursue that approach, to make sure that the naloxone is getting to the people at the highest risk [of overdose].”

Other harm-reduction options

According to the Commonwealth Fund, another option for states is to allow for “consumption sites,” where individuals can use drugs legally under the supervision of trained staff. At these sites, individuals also get connected to treatment and other services. Legislative proposals in Illinois this year (HB 2 and SB 78) would allow for such sites.

Among the 50 U.S. states, Davis points to Oregon as a potential model on how to approach the broader issue of opioid use disorder and its consequences — including the rise in overdose deaths. In that state, as the result of a voter-approved measure from 2020, the personal possession of drugs has been decriminalized, and revenue from marijuana sales is being dedicated to a Treatment and Recovery Services Fund. Money from that fund supports 15 addiction recovery centers as well as a grant program to improve access to community-based addiction services.

“If we really think of substance abuse disorder as a chronic, relapsing disease of the brain for which effective treatments are available, we should not be arresting people for having that condition,” Davis says. “We should be making sure that everybody who wants treatment can get it.”

The post New bills and laws aim to stem rapid rise in fentanyl-related overdose deaths appeared first on CSG Midwest.