Out in the fields of western Michigan, before he became a state lawmaker, “Farmer Rog” was doing a job that ultimately would help shape his legislative agenda. Agricultural products — “off-grade,” but edible and healthy — were regularly being delivered every week to Roger Victory’s produce facility.

“What was our job? Was it to recondition [that product], to get it into the food system?” Victory said. “No, it was just to be disposed of — semi-loads of product with $10,000, $20,000 of potential market value. And it wasn’t just one semi. It was two semis, three semis a week.”

Across the Midwest, lots of food is being produced by farmers like Victory, yet there are households without enough to eat.

“Couldn’t there be a better way?” Victory thought as he composted that “excess product” in his fields. Finding answers has been a legislative priority of his ever since coming to Lansing.

“Couldn’t there be a better way?” Victory thought as he composted that “excess product” in his fields. Finding answers has been a legislative priority of his ever since coming to Lansing.

Victory told that story in July to fellow legislators as part of his introduction of a featured session at the Midwestern Legislative Conference Annual Meeting on “Food Security: Feeding the Future” — the focus of his MLC Chair’s Initiative for 2023.

“This is a truly unifying issue,” Victory said. “We all have constituents who struggle every day to put food on their tables and to feed their families.”

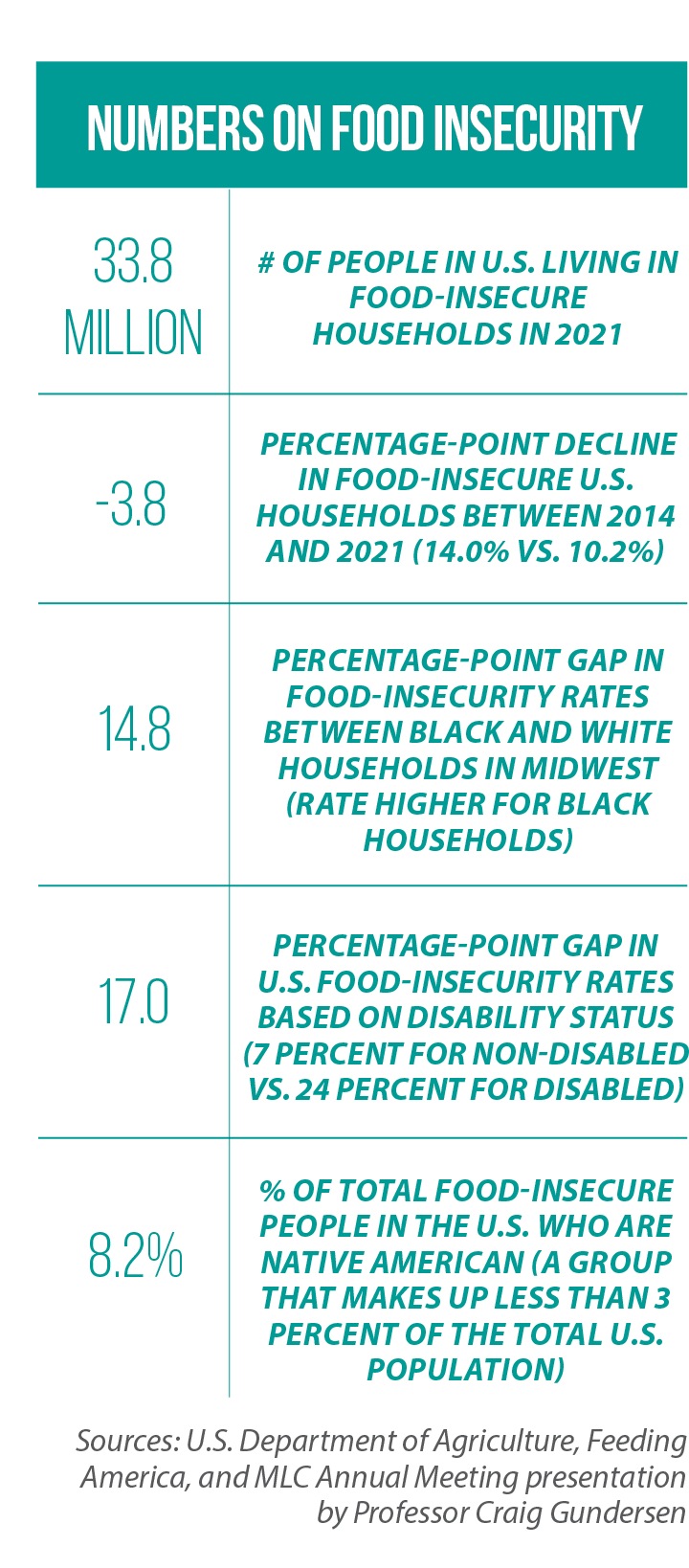

Nationwide, more than 9 million U.S. children and more than 24 million adults living in a household with some degree of “food insecurity,” including some households reporting “low” or “very low” levels of food security.

Recent policy actions in Victory’s point to the possibility of some “win-wins” for legislators and their constituents. For instance, Michigan is providing more dollars to a grant program for food banks to purchase excess food from agriculture producers in order to better meet the emergency food needs of households. New investments are being made to build stronger local food systems and supply chains. And state funding is going to a Double Up Food Bucks program that opens new markets for farmers’ locally grown foods while boosting support for individuals who receive food-assistance benefits. (See bottom of this page for details on these and other recent state actions in the Midwest.)

Recent policy actions in Victory’s point to the possibility of some “win-wins” for legislators and their constituents. For instance, Michigan is providing more dollars to a grant program for food banks to purchase excess food from agriculture producers in order to better meet the emergency food needs of households. New investments are being made to build stronger local food systems and supply chains. And state funding is going to a Double Up Food Bucks program that opens new markets for farmers’ locally grown foods while boosting support for individuals who receive food-assistance benefits. (See bottom of this page for details on these and other recent state actions in the Midwest.)

“There’s enough of us now who believe that we can solve this problem; I don’t think we want to just manage it anymore,” Phil Knight, executive director of the Food Bank Council of Michigan, said about food insecurity, singling out some of the advances in that state during a panel discussion at the MLC Annual Meeting.

Formula for success: Strong economy plus expanding reach of SNAP

Rates of food insecurity are regularly measured by the federal government, and are based on responses from U.S. households to a series of survey questions.

“It’s become the leading indicator of well-being for vulnerable households in America; I really think it has surpassed the poverty rate,” said Professor Craig Gundersen, a leading researcher on food insecurity and the Snee Family Endowed Chair at the Baylor University Collaborative on Hunger and Poverty. Those surveys show that progress has been made in recent years: Rates of food insecurity among U.S. households fell 40 percent between 2014 and 2021, Gundersen told legislators.

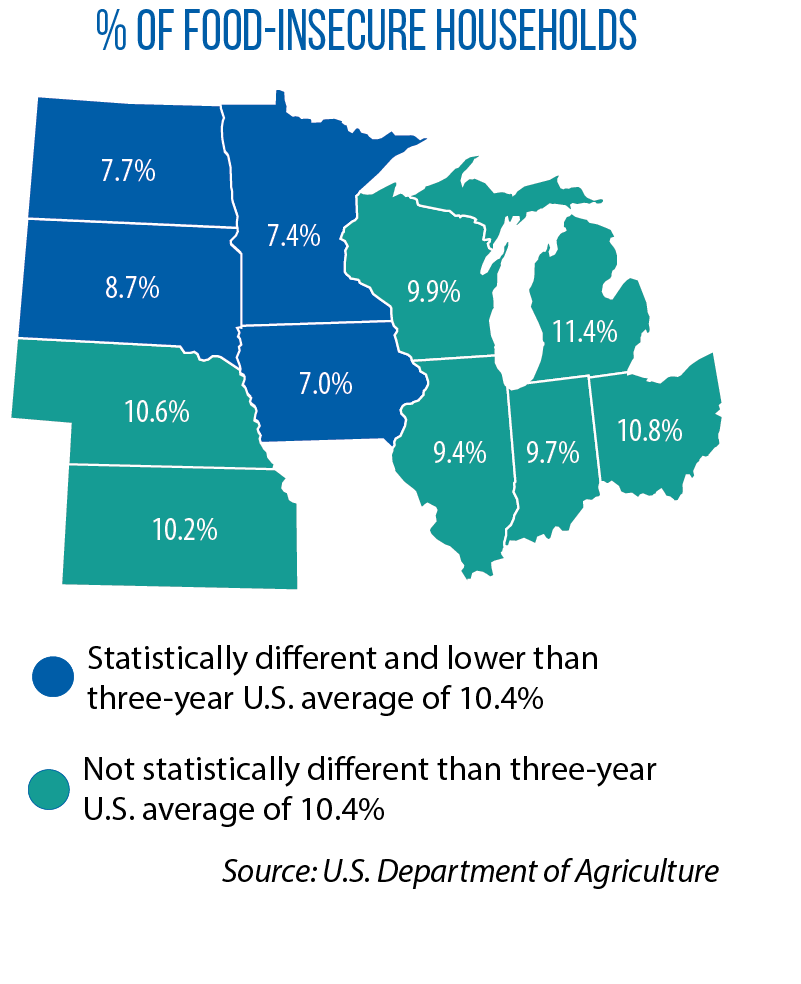

The most recently available federal data puts the U.S. rate of food-insecure households at 10.4 percent (when averaging the years 2019, 2020 and 2021). Four Midwestern states — Iowa, Minnesota, North Dakota and South Dakota — have a “statistically significant” lower rate than the national average. Every other state in the region is close to the national average, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s “Household Food Security in the United States in 2021.”

The most recently available federal data puts the U.S. rate of food-insecure households at 10.4 percent (when averaging the years 2019, 2020 and 2021). Four Midwestern states — Iowa, Minnesota, North Dakota and South Dakota — have a “statistically significant” lower rate than the national average. Every other state in the region is close to the national average, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s “Household Food Security in the United States in 2021.”

Authors of that USDA report cite several contributors to the state-by-state variations. On the policy side, state laws and programs affect access to unemployment insurance, nutrition assistance and the earned income tax credit. In turn, access to these as well as other safety-net and/or anti-poverty programs influences rates of food insecurity.

Differences in state-level economic characteristics play a role as well. For example, lower average wages lead to higher rates of food insecurity, as do higher costs (for housing and food, in particular) and unemployment rates. At the household level, families with children have higher-than-average rates of food insecurity (12.5 percent in 2021). This is especially true of households with children headed by a female with no spouse: Nearly 1 in 4 of these households report being food insecure, compared to 7.4 percent of married-couple households.

What has led to the recent decline in overall U.S. rates of food insecurity? Gundersen pointed to two factors during his July presentation to the MLC: Strong economic growth “raised up” more households, while enrollment in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program — which provides food assistance to low-income people — also rose.

Not only did SNAP reach more households in need, he added, policy changes increased the level of benefits.

Though recognizing that SNAP has its critics, Gundersen praised the federal-state program and its structure. According to Gundersen, it reaches those most in need, gives them dignity and autonomy when making food purchases, can be used at virtually all food retail outfits, and does not discourage work among recipients.

“Every discussion about food insecurity … has to involve SNAP,” Gundersen said about the nation’s largest hunger-fighting program.

Each month, around 40 million Americans receive help from the program, with benefits provided via an electronic benefits transfer card that is only redeemable for food purchases. In fiscal year 2022, the average monthly benefit, per household, was $438.99.

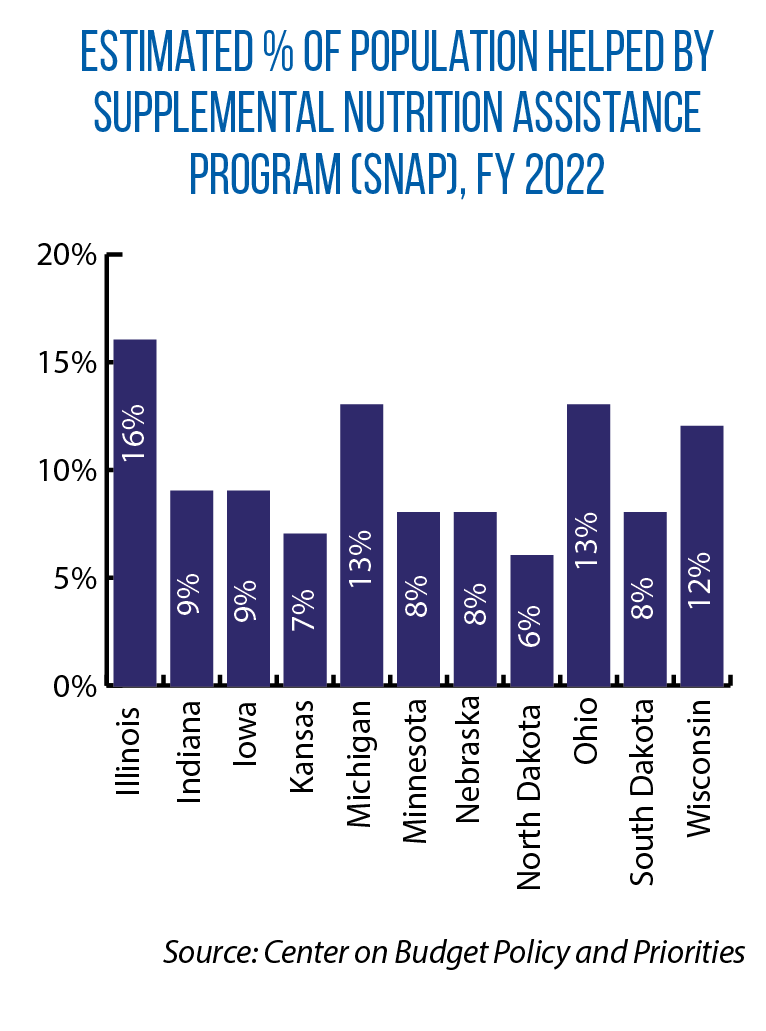

According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, the percentage of state residents in the Midwest participating in SNAP in FY 2022 ranged from a high of 16 percent in Illinois to a low of 6 percent in North Dakota. Nationwide, the center says, more than 65 percent of SNAP participants are in families with children; 36 percent are in families with members who are older adults or disabled; and 41 percent are in working families.

According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, the percentage of state residents in the Midwest participating in SNAP in FY 2022 ranged from a high of 16 percent in Illinois to a low of 6 percent in North Dakota. Nationwide, the center says, more than 65 percent of SNAP participants are in families with children; 36 percent are in families with members who are older adults or disabled; and 41 percent are in working families.

Among Gundersen’s policy ideas for state legislators: Find ways of streamlining the SNAP recertification process so that households in need of assistance don’t lose benefits. “There is [too much] churn where people are off the program and back on the next month because they missed a notification or there’s some sort of glitch,” he said. “Let’s make recertification a lot more streamlined.”

One recent example from the Midwest: This year’s passage in Indiana of SB 334, which directs state administrators of SNAP to simplify the certification process and lengthen renewal periods for the state’s disabled and older residents.

A ‘meal gap’ among certain groups, and in many rural areas

Gundersen also pointed out some not-so-good news to the region’s legislators about trends in food insecurity. He said rates remain high among certain groups, particularly African Americans, Native Americans and people with disabilities. Those disparities remain even when controlling for income.

“The gap between Whites and Blacks in the Midwest is astounding compared to other parts of the country,” Gundersen said. (It’s nearly 15 percentage points.)

Nationwide, too, the most recent USDA study showed much higher rates of food insecurity among Black and Hispanic households: 19.8 percent and 16.2 percent, respectively, compared to 7.0 percent of White households.

Nationwide, too, the most recent USDA study showed much higher rates of food insecurity among Black and Hispanic households: 19.8 percent and 16.2 percent, respectively, compared to 7.0 percent of White households.

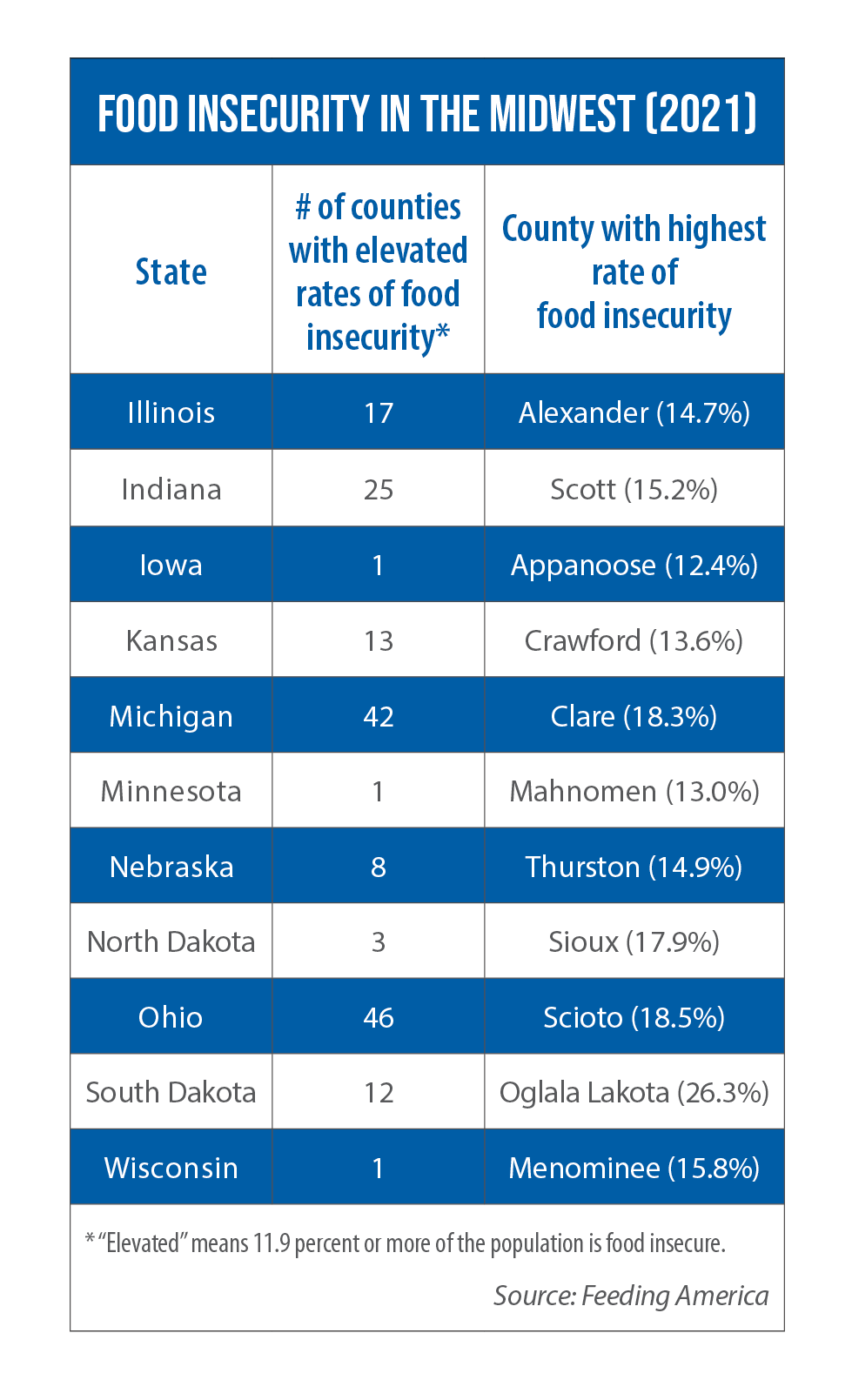

There are other notable disparities as well, across the region and entire United States; for example, food insecurity tends to be higher in rural areas. According to the hunger-relief organization Feeding America, which tracks county-level data for its “Map the Meal Gap” study, 89 percent of the U.S. counties with the highest rates of food insecurity are rural.

In the Midwest, Michigan has 42 counties with elevated rates of food insecurity (11.9 percent or more of the population), and nearly all of them are concentrated in the state’s northern region and Upper Peninsula. Many of Ohio’s 46 counties with higher-than-average food-insecurity rates are in the rural, southeast part of the state. In South Dakota’s Oglala Lakota County, 26.3 percent of the residents report being “food insecure,” one of the nation’s highest rates. This county has a mostly Native American population. In four other Midwestern states — Minnesota, Nebraska, North Dakota and Wisconsin — the counties with the highest rates of food insecurity also have high numbers of Native Americans.

According to Feeding America, of the 34 million people in the United States experiencing food insecurity, 8.2 percent are Native American, a group that makes up less than 3 percent of the U.S. population.

Disability: ‘The leading predictor of food insecurity’

Here is another striking disparity: Nationwide, 93 percent of households with non-disabled adults are “food secure,” but the rate falls to 76 percent for households with disabled adults between the ages of 18 and 64.

Here is another striking disparity: Nationwide, 93 percent of households with non-disabled adults are “food secure,” but the rate falls to 76 percent for households with disabled adults between the ages of 18 and 64.

“The leading predictor of food insecurity in the United States today is disability status, especially mental health,” Gundersen said. “So if we want to talk about food insecurity in the United States today, it’s really a story about disability. … Figuring out how we can improve the wellbeing, how we can make things easier for those facing disabilities, has to be part of [the] discussion.”

Addressing food security goes hand in hand with addressing the nation’s mental health crisis, he said. And for individuals who have difficulty traveling due to a disability, states can help by making SNAP certification simpler and by investing in programs that enable the home delivery of meals. Knight said some Michigan food banks are partnering with private businesses such as DoorDash, and through another pilot initiative, “fresh food pharmacies” are opening inside of health clinics.

“How do we get food to people who can’t get to the food? We’re trying to be creative and innovative in that,” Knight said, adding that states can help by partnering with local food banks on these programs.

The causes and effects of being food-insecure

Panelists for the MLC meeting session also pointed to various studies showing how health outcomes and costs, as well as the academic success of young people, are tied to food security. “One of the great predictors of graduation rates is third-grade reading levels, right?” Knight said. “But if they’re not well fed, they will never be well read.”

University of Toronto Professor Emerita Valerie Tarasuk, a pioneer of research on food insecurity in Canada, said the correlation with health also is clear.

University of Toronto Professor Emerita Valerie Tarasuk, a pioneer of research on food insecurity in Canada, said the correlation with health also is clear.

“[It] takes a huge toll on health and on health care budgets,” she said. “An adult in Canada who is in a severely food-insecure household, in the course of a 12-month period, burns up more than double the health care dollars of somebody else who’s food-secure.”

Canada does not have a food-based assistance program such as SNAP. It instead relies on cash transfers to provide low-income households with the financial resources they need. According to Tarasuk, those transfers have not kept pace with recent spikes in the price of food, housing and other necessities. As a result, food-insecurity rates in that country have been on the rise.

It’s a reminder, too, that income levels and a social safety net are not the only determinants of food insecurity; prices of goods, especially food, play a role as well. According to Gundersen, giving farmers “the freedom to operate” helps keep food prices low and contributes to food security. Tarasuk, meanwhile, urged legislators to look at broader economic metrics — for example, the wages being paid to workers.

“We can see very clearly from Canadian data that even a small increase in the minimum wage reduces the rate of food insecurity,” she said.

Another session panelist, Michigan State University Professor M. Jahi Johnson-Chappell, wrote a book detailing how a community in Brazil dramatically reduced hunger. He shared his global insights during the discussion. The first step, Johnson-Chappell said, was having political leaders recognize food as a “right of citizenship.”

That didn’t mean directly providing every person with a meal, he said, but instead creating conditions to ensure access to it (just as a right such as free speech doesn’t guarantee access to a newspaper, but creates an environment where it is available to citizens).

Once the “right to food with dignity” was recognized and taken seriously, Johnson-Chappell said, a series of interventions followed. Central to the effort were new partnerships with local farmers.

“We saw decreases in infant mortality and infant malnutrition of 50 to 70 percent, a decrease in diabetes of about 30 percent, and it was one of the few Brazilian cities that saw increases in fruit and vegetable consumption,” said Johnson-Chappell, director of Michigan State’s Center for Regional Food System.

The post ‘Truly unifying issue’: A look at food insecurity and the role states play in addressing it appeared first on CSG Midwest.