New Mexico secretary of state works collaboratively to improve elections for Tribal communities.

By Lexington Soures

When New Mexico Secretary of State Maggie Toulouse Oliver served as Bernalillo County clerk, she learned firsthand the challenges of translating election language. In the Navajo Nation, where Diné bizaad is spoken, no direct translation exists for Republican or Democrat.

When Toulouse Oliver attended her first Navajo Nation chapter meeting, she learned more about how election and political terms may differ from community to the next. While one community may identify a Democrat as a “donkey rider,” another may use the phrase “someone who walks with a donkey.” This experience led her to prioritize word choice.

“That was that was one of the big, mind-blowing things for me — how do we communicate,” Toulouse Oliver asked. “What terminology do we use even within the context of the Navajo language to make sure that that idea is communicated accurately? That is one of our big challenges.”

Toulouse Oliver acknowledged that assimilation and language eradication occurred in many Native communities. However, some voters maintain a traditional lifestyle.

“I have people in New Mexico that live in hogans with no running water and no electricity,” Toulouse Oliver said. “They live their very traditional way of life and that has not changed in their lifetime. So, what do we want to do? Leave these folks behind when it comes to the voting process? No, we have to come to them.”

Before 1948, the New Mexico Constitution did not allow certain Native people to vote. Miguel Trujillo, a member of the Pueblo of Isleta and a World War II Marine Corps veteran, then stepped in to challenge the constitution’s language. Prior to Trujillo coming forward, voting rights were denied to Natives who did not pay private property taxes on reservations despite having paid all state and federal taxes. With the right to vote eventually secured, Native voters faced limited access to voting locations and a lack of translated voting materials that included instructions, notices and even ballots.

While some counties complied with federal law and Department of Justice intervention, others were slow to adapt their processes.

“There’s sort of a history of really needing to get with it in terms of complying with federal law,” Toulouse Oliver said. “Fast forward to today, we have one letter of agreement left in existence for one county. We have the Native Voting Task Force in my office and then we passed the Native American Voting Rights Act this year.”

This year, New Mexico’s Legislature passed HB 4, covering a variety of voting rights issues including the first Native American Voting Rights Act. The bill expands a nation, tribe or pueblo’s ability to apply for amended voting locations and a secure ballot drop box, and allows voters to use government buildings as their mailing address.

“We gave them the opportunity to ask for and receive a secured monitor container, also known as a drop box, for once they receive that ballot, especially if they receive it at that tribal government building,” Toulouse Oliver said. “They can also deposit the ballot back at the government building. They don’t necessarily need to send it back through the mail.”

Local tribal governments were also provided much more flexibility through the bill. As a result, they can now establish the site of their polling locations, in addition to choosing where and how long early voting takes place.

“We’re hoping all of those things go a long way towards really improving some of those ballot access challenges,” Toulouse Oliver said.

Implementation is the secretary of state’s next major challenge. She and her office plan to provide resources to Native communities that include the new options and work to determine what is best for each community.

Otero County Clerk Robyn Holmes said the bill helps solve some challenges her county faces, such as a central address for ballot delivery. Otero County has around 12,196 Native voters who live on the Mescalero Apache Reservation.

“We work as county clerks with the Secretary of State’s Office and we come up with things that we feel will help voter outreach and get people out to vote,” Holmes said. “For that, we get along very well with our secretary of state. Our legislator’s listen to us and subsequently they pass the laws.”

Holmes said this hasn’t always been the case, though. However, over time, and despite party differences, clerks and legislators have been able to work together with Toulouse Oliver to communicate voters’ needs.

“We’ve been very fortunate with the offices of the secretary of state and clerks working so well together. It’s not always perfect, but for the most part, we can work it out and make it work for everybody,” Holmes said. “It’s different when you have large cities in one county and then you have very small, rural counties with two people working in their offices. It’s hard to implement bills and policies and procedures exactly the same for everybody.”

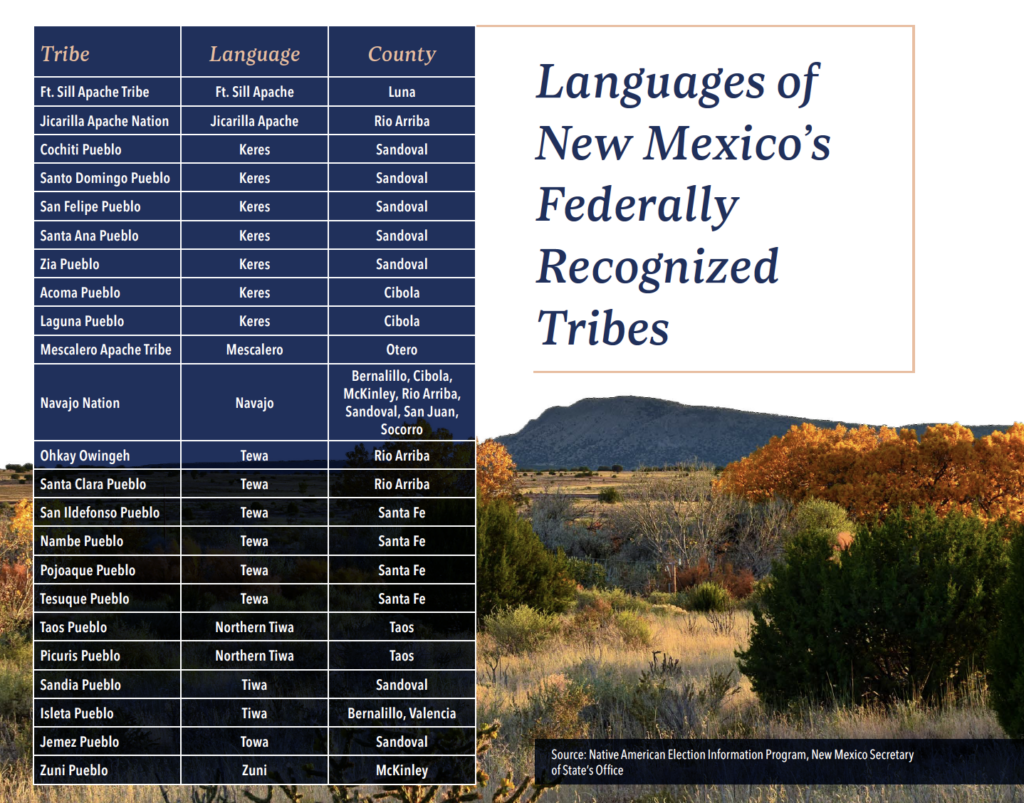

Toulouse Oliver recognizes that policy cannot be copied and pasted between New Mexico’s 23 federally recognized tribes, who speak eight different languages. The Native American Voting Rights Task Force was created in 2017 by the secretary of state to better connect with the needs of New Mexico’s three main tribes, including the Navajo Nation, the Pueblos and the Apache Tribes. The task force has representation from all of these groups, as well as an urban Native representative, but limits membership to a few members to remain productive. Members collaborate to inform the Secretary of State’s Office on areas of outreach and improvement, in addition to useful and appropriate language and messaging.

“We don’t want to copy and paste, first of all,” Toulouse Oliver said. “We don’t want to treat all of our tribal areas the same and all of the individuals because they have different cultures, different languages.”

While Holmes doesn’t need to translate ballots, her office does translate the portion of the proclamation affecting the reservation. These translations are recorded and played through the local radio station.

Because each tribe has a unique voting culture, including who can vote and what positions are open for election, it is important to approach each tribe with their culture in mind, according to Toulouse Oliver.

“There are just so many culture and language ins and outs that, as a white woman from Albuquerque, New Mexico, I am not the expert, nor am I ever going to try to be, nor am I ever going to try to superimpose what I think works in tribal areas,” Toulouse Oliver said. “I want folks to tell us what works in [their] community. What creative ideas do you have? How can we invest in those? How can we live those? That’s kind of the work that [the task force members] do.”

Despite progress, Native voters continue to face challenges, including limited ballot collection services, language translation and the digital divide. A report by the Native American Rights Fund found voting barriers typically fell under 11 categories, including geography, infrastructure concerns, nontraditional addresses and IDs, and the digital divide. The 2020 report found only 66% of eligible native voters across the nation are registered.

Toulouse Oliver uses buildings of cultural importance, like chapter houses in the Navajo Nation, to help increase access to polling locations.

“We use schools, we use other public buildings where available, but even then, you’re often talking about an individual having to drive 50 to even as many as 200 miles to get to the nearest in-person polling place,” Toulouse Oliver said. “We’re trying to expand — as much as we can — mobile early voting units [that travel] to these communities to be there for two or three days to a week during the early voting period.”

Because many who live on reservations receive their mail at a post office box or reside in remote, nontraditional areas without valid U.S. mailing addresses, New Mexico law allows voters to describe their addresses.

“We’ve done a really good job in New Mexico for years at addressing the issue of not having a standard physical address,” Toulouse Oliver said. “You can literally draw a map, write a description or say, ‘I live three streets down from the giant cottonwood tree after you get off of the exit at Highway 85.’”

While voters are able to describe their address, this can be challenging when ballots or other voting materials need to be delivered. Toulouse Oliver said mail delivery can be infrequent, or that individuals may not receive mail at their home. In New Mexico HB 4, the Legislature addressed issues regarding ballot delivery, allowing individuals to use their local tribal government building as an individual’s mailing address. Toulouse Oliver said this eases the process because the U.S. Postal Service delivers to every tribal government building in the state.

“One good thing that came out of this last session was that the Legislature passed the law that on reservations they could have one location, like at their community center or wherever they designate,” Holmes said.

“They’ve created this law that allows our reservation to say, ‘Anybody that wants to request a ballot that was on the reservation, you can have it mailed back to our community center and we’ll get it to you,’ as opposed to going to their address where apparently they feel like they don’t get their mail all the time.”

Native voters living in urban areas face challenges that are different than those on reservations. Based on the population, some urban areas are required to have translated ballots or a translator on call. Many urban native voters have access to broadband internet and are aligned with their nonnative neighbors, but there may be more cultural challenges.

“I think there is a particular part of the Native community that may live physically within an urban area. They live in Albuquerque, New Mexico, or Gallup, New Mexico, or Farmington, but they still consider their whole chapter and maybe their parents’ or their grandparents’ residence [to be] where they actually live, where they are from,” Toulouse Oliver said. “In many ways, it’s interesting to see our urban Native voters needing to go back to that place of origin in order to vote or to apply for and get an absentee ballot. The challenge there then is just going like we would do with any other group. What is what makes you interested in wanting to vote? How can we make it easier for you to register and get your ballot?”

Another challenge is the size and resources available for some communities. A tribal community’s size or economic resources may lead them to be more invested in federal elections, or the opposite may be true. Toulouse Oliver added that opinions on the importance of elections may differ even within communities, increasing the challenges of civic education.

Many of these smaller communities also struggle with access to broadband connectivity or phone service. This creates an additional challenge for election officials.

“How do we make sure those voters have information and access to the ballot box in the same way that a voter who lives in Gallup or Shiprock,” Toulouse Oliver said. “Those are the kinds of challenges we’re trying to navigate.”

One program tackling this challenge is the Native American Election Information Program. Created in 1988, the program facilitates voter education programs in counties with the largest Native populations. The program educates communities on the election process, upcoming elections, and provides election assistance for both tribes and county clerks to ensure compliance with federal and state law.

Toulouse Oliver increased the number of staff to better cover the needs of Native communities. The liaisons translate necessary documents into both the appropriate language and the correct media. For example, publication requirements necessitate the use of radio in some communities.

“It’s a lot of work for two people, but they do an amazing job,” Toulouse Oliver said. “They’re the ones who are physically out there in the communities, hearing from those tribal leaders on what they need, what we need to be doing better and what is something that they need from us versus what is something they need from county government. Sometimes we can all three work together to get something accomplished.”

In counties with a larger Native population, a tribal liaison works with the county clerk to provide tools or resources. As well, while not required, each Native community hires poll workers from their community. These workers provide a cultural connection and can help with any language or assistance needs. Toulouse Oliver said this lessens the stress and intimidation of voting, especially for new or infrequent voters.

Holmes said she does not work with a liaison, but she has built close relationships with community members, like an attorney on the reservation. For voter drives, a member of the New Mexico Secretary of State’s Office joins Holmes’ office.

“I’m friends with the attorney up there,” Holmes said. “We make sure we have an open dialogue between us. If they need anything or if we need something, [we’re both very good to accommodate each other].”

Looking ahead, Toulouse Oliver hopes to expand her office’s work with the Native community. A facilitator will join the Native American Voting Task Force to help the group explore programs and funding for the future. Toulouse Oliver said the successes, or failures, of this “regearing” phase will determine future programs.

The work of the Secretary of State’s Office with the Native community can, in a larger sense, be applied to other minorities. Toulouse Oliver said that while not all marginalized communities may face the same challenges, other voters benefit from the lessons learned from listening to communities’ needs and allocating appropriate resources to them.

“As an elected official, you have to be open to saying, ‘You tell me what you think your community needs. I’m not here to tell you what I think it needs,’” Toulouse Oliver said. “If it’s not me, who can I give tools and resources to that are needed to be that person, that messenger. Not all marginalized communities have the same challenges. [We’re] not just taking that cut and paste approach.”