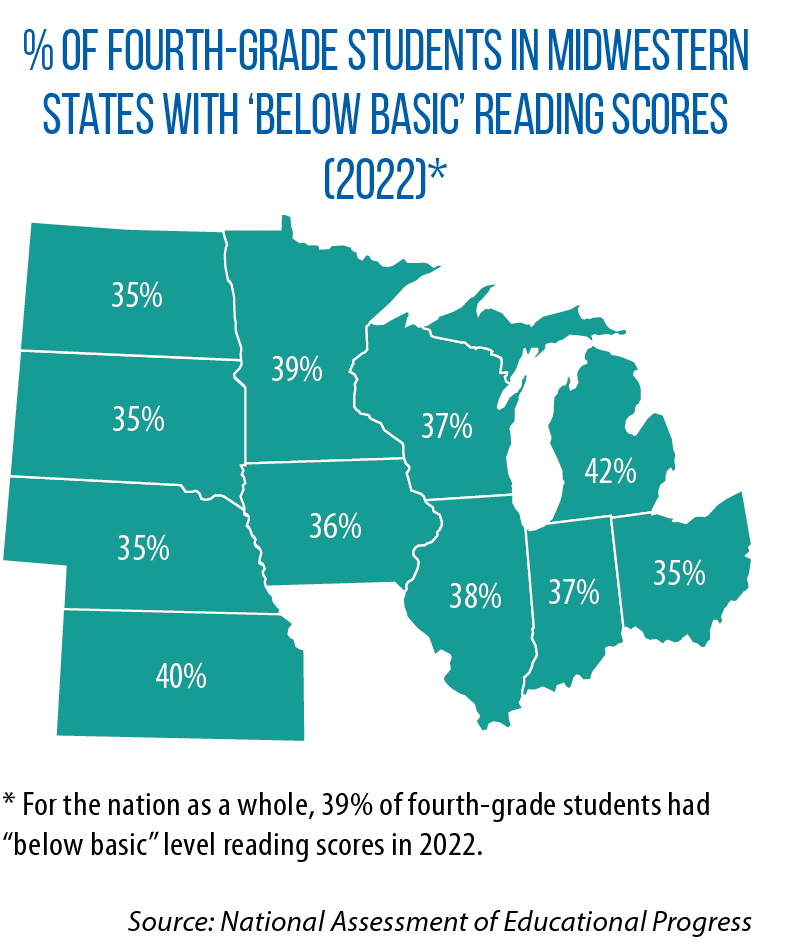

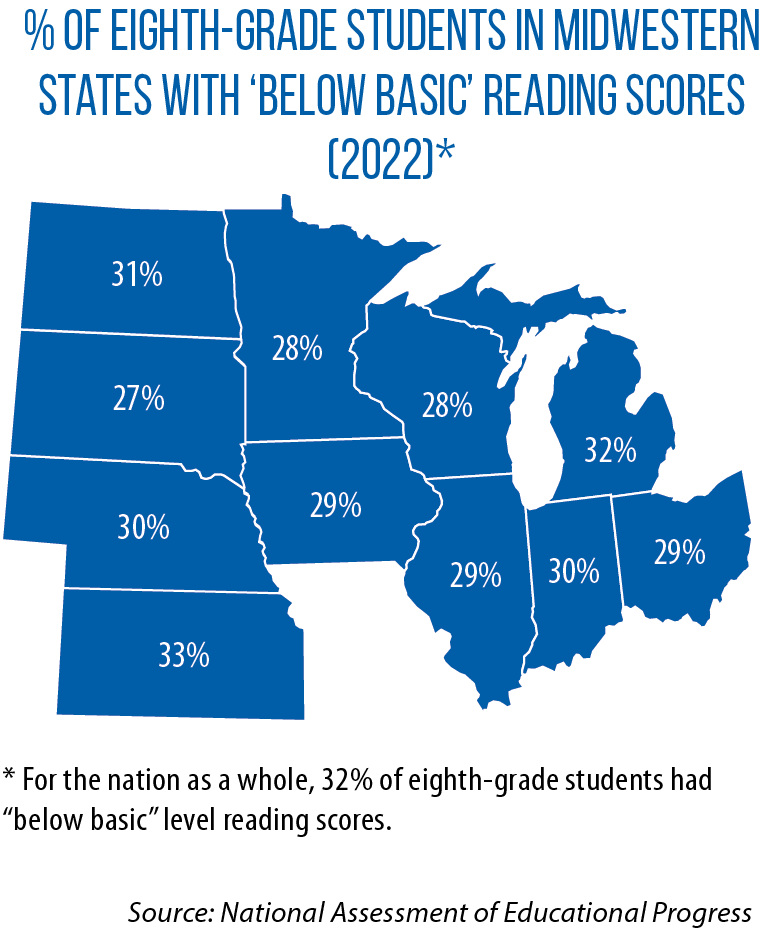

In the Midwest, drops in students’ test scores on reading are widespread and, in many states, predate the COVID-19 pandemic. One group that has taken notice and recent action to reverse that trend: state legislators.

“Kids that don’t know how to read or aren’t reading at a proficient level by third grade are exponentially more likely to drop out of school,” notes Indiana Rep. Jake Teshka, chief author of a new law on reading in his state.

The research is definitive on that point, he adds, and the consequences also are clear. Young people don’t attain the postsecondary credentials they need for economic and career success, and the state as a whole is left with a workforce problem.

The research is definitive on that point, he adds, and the consequences also are clear. Young people don’t attain the postsecondary credentials they need for economic and career success, and the state as a whole is left with a workforce problem.

“Jobs coming to Indiana are increasingly going to require some sort of postsecondary education,” Teshka adds.

He believes a new law in Indiana can help turn around those trends in reading performance.

In Wisconsin, Rep. Joel Kitchens authored a like-minded bill in his home state, with some of the same long-term concerns about student outcomes in mind.

“When people ask me, ‘What scares you the most about the future,’ [it] is seeing more and more people trapped in that cycle of poverty, one generation after the other,” Kitchens says. “The only chance we have of breaking that is education. And basically, if we don’t get [students] reading early, it’s just not going to happen.”

Laws in Indiana, Wisconsin and other states are revamping schools’ reading instructional strategies and promoting (sometimes requiring) approaches that adhere to what is known as the “science of reading,” or SoR.

Context of new laws on reading instruction

Although not comprised of a universally recognized curriculum model, SoR is an approach to reading instruction that emphasizes phonetic learning, the sounding out of letters and words. For the last few decades, a “reading war” of sorts has waged throughout academia regarding reading instruction.

Is phonics the best approach? Or do other strategies work best for students?

For example, with the “three-cueing” model, an emphasis is placed on students using context clues and analyzing syntax in order to understand written language. In practice, a teacher using this method would prompt students, or “cue” them, to ascertain the meaning of a word in a sentence by asking a series of questions: Does it make sense? Does it sound right? Does it look right?

For example, with the “three-cueing” model, an emphasis is placed on students using context clues and analyzing syntax in order to understand written language. In practice, a teacher using this method would prompt students, or “cue” them, to ascertain the meaning of a word in a sentence by asking a series of questions: Does it make sense? Does it sound right? Does it look right?

The problem with this method, according to critics, is this style of instruction simply makes students better guessers. It’s more akin to the strategies used by people who have difficulty reading, they say.

Proponents of the recently enacted state laws say SoR is more closely aligned with the tenets of cognitive science. That’s because lessons built on phonemic awareness and phonics better connect how children auditorily learn how to speak, a primal ability of humans, to how they learn to read, a more complex and relatively modern skill.

“We have tangible physical evidence as far as the way that the brain works and the way that orthographic mapping works and the way that we commit words to memory,” Teshka says. “And the process by which we do that is all encompassed in this body of research called ‘science of reading.’ ”

Teshka’s goal with this year’s HB 1558 (signed into law in May) is to make sure evidence-based instruction from that research is used in Indiana classrooms.

The SoR movement has also gained traction in part because of recent progress in Mississippi, a state that traditionally has had among the nation’s lowest reading scores. A turnaround has occurred in that state over the past decade, since passage of the Literacy-Based Promotion Act and the Early Learning Collaborative Act.

With those laws in place, money started going toward SoR-based professional development for all early-grade teachers and school administrators.

Mississippi schools also received new resources from the state, including literacy coaches — individuals with advanced degrees who work with teachers as well as one-on-one with students.

“[The] coaches were put through a rigorous interview process to make sure they had the right background knowledge and knew how to work with adults,” former Mississippi State Superintendent Carey Wright said during an interview earlier this year with McKinsey & Company.

“We were strategic in how we deployed these people and how we built capacity for teachers and leaders.”

Between 2013 and 2019, average fourth-grade reading scores in Mississippi increased significantly. Additionally, 65 percent of students in this grade were reading at a basic level or higher, up from 53 percent in 2013. These advances were also seen across multiple racial and ethnic groups.

The post With ‘science of reading’ laws, states eye turnaround in recent trends appeared first on CSG Midwest.