Over the past decade, every state in this region has changed its laws on civil asset forfeiture, a process that allows for the seizure and permanent taking of property that is related to a criminal offense. In some states, those changes have included adding some kind of criminal-conviction requirement for the property to be subject to forfeiture.

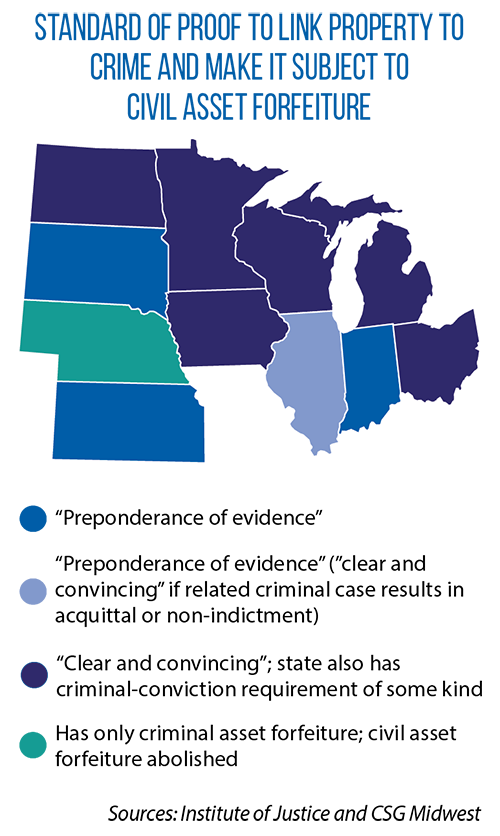

Without such language, the process in most states is unrelated to outcomes in a criminal case. That’s because the property, not an individual, is the subject of the case in a civil proceeding. The standard of proof in these proceedings is lower than “beyond a reasonable doubt,” with one of two standards applied in the Midwestern states: “preponderance of the evidence” or “clear and convincing” (see map).

Without such language, the process in most states is unrelated to outcomes in a criminal case. That’s because the property, not an individual, is the subject of the case in a civil proceeding. The standard of proof in these proceedings is lower than “beyond a reasonable doubt,” with one of two standards applied in the Midwestern states: “preponderance of the evidence” or “clear and convincing” (see map).

The addition of a criminal-conviction requirement has been part of a broader trend in legislatures that aim to better protect property owners. In the Midwest, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, North Dakota, Ohio and Wisconsin are among the states where such a prerequisite has been added to statute.

However, this criminal-conviction requirement sometimes only applies in certain types of forfeiture actions. For example, one approach is for states to require a criminal conviction only in cases involving property valued at a certain statutorily defined amount: under $5,000 in Iowa (SF 446 of 2017); $50,000 or under in Michigan (SB 2, HB 4001 and HB 4002 of 2019), and under $15,000 in Ohio (this was the amount set under HF 347 in 2017; the threshold changes based on inflation).

The Institute of Justice, which has backed changes to state civil asset forfeiture laws, says these criminal-conviction requirements still leave many property owners vulnerable. First, the institute notes, the burden can be on the owner to take legal action and contest the forfeiture; second, the state requirement often is satisfied by the conviction of any person related to the underlying criminal activity — not necessarily the property owner. As a result, an “innocent owner” still risks having his or property taken.

The criminal-conviction requirement is one example of how legislatures recently have altered the rules of civil asset forfeiture, but kept it as a tool for law enforcement. Other changes have:

- Raised the standard of proof for property to be subject to forfeiture — Over the past decade, Iowa, Michigan, North Dakota and Ohio are among the states where the standard has been raised to “clear and convincing evidence.”

- Added protections for “innocent owners” — An innocent owner is a person who did not know of or consent to the illegal activity connected to the property. As part of the civil asset forfeiture process, states provide a mechanism for these “innocent owners” to get back the confiscated property. Legislatures in states such as Iowa and Wisconsin (SB 61 of 2018) now make the government bear the burden of proof, rather than the owner having to prove his or her innocence.

States also have placed new reporting requirements on law enforcement and changed how proceeds from the sale of forfeited property can be used; for example, in Wisconsin, money now goes to the state’s Common School Fund.

Nebraska is one of four U.S. states that has abolished civil asset forfeiture (LB 1106 of 2016).

Question of the Month highlights an inquiry sent to the CSG Midwest Information Help Line, an information-request service for legislators and other state and provincial officials from the region.

The post Question of the Month | December 2023 | Civil Forfeiture appeared first on CSG Midwest.