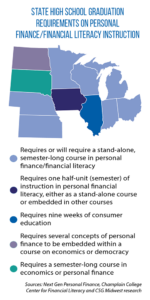

In recent years, most Midwestern states have legislatively revised their respective high school graduation requirements to include mandated instruction in financial literacy.

In 2023 alone, three states (Indiana, SB 35; Minnesota, HF 2497; and Wisconsin, AB 109) enacted laws requiring one semester of financial literacy education starting with the graduating class of 2028.

The Wisconsin measure, signed by the governor in December, marked the culmination of a multi-year journey.

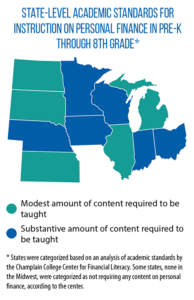

Back in 2017, lawmakers approved AB 280, which tasked local school boards with adopting and incorporating financial literacy curriculum standards in all K-12 grades. The Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, in turn, developed state standards to guide this coursework.

According to the state’s latest standards, students are expected to understand, for example, the nuances of money management, financial risk assessment, how to save and invest, and how to achieve debt resolution.

Sen. Joan Ballweg, a co-sponsor of both the 2017 and 2023 legislation, says that despite the availability of state standards, many Wisconsin schools were still not offering the instruction to students.

“[In 2023], 34 percent of schools guaranteed students would have one semester of personal finance before graduating, and 59 percent [of students] had the option of taking an elective personal finance education course,” Ballweg says.

That wasn’t nearly good enough for her and other believers in the need to build students’ financial literacy.

“The stand-alone class is going to be able to incorporate more of what financial literacy is,” Ballweg says.

“Everything from talking about investments, talking about amortization schedules, talking about your own budgeting, the ramifications of what it takes to pay for college, [to] buying a vehicle on your own and the insurance that’s going to come with it.”

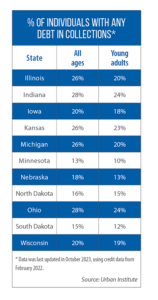

Chris Caltabiano, chief program officer of the nonprofit Council for Economic Education, says research supports the taking of a designated financial literacy course.

“With a well-prepared, well-trained teacher [it] has positive downstream effects on [students’] financial behaviors and outcomes,” he says.

“Students who have had that dedicated course tend to have higher credit scores; they tend to have lower debt default rates. If they choose to go to college, they tend to make decisions that are more financially advantageous, [such as] making the decision to take out a public loan versus a private loan.”

Ballweg pursued legislation in 2022 (SB 841) requiring a full academic year of financial literacy starting with the class entering high school that fall. After getting feedback that one full year could be overly burdensome for some schools, she returned with AB 109 and its semester-long requirement. The bill also extends the implementation time frame (to the class of 2028).

Questions have been raised in Wisconsin about the actual teaching of the new requirement — both in terms of finding qualified educators in the midst of a national teacher shortage and how to fund professional development training for educators.

More flexibility for schools in Iowa

Concern over finding enough teachers is one of the reasons that Iowa legislators last year modified their laws on financial literacy.

In 2018 and 2019, the Legislature adopted a series of bills making Iowa the first Midwestern state to require instruction in a stand-alone course.

SF 475 of 2018 spells out the type of instruction to be covered in this course: for example, wealth building and college planning, credit and debit, consumer awareness, insurance coverage, and the advantages and disadvantages of buying and renting real estate.

A second measure, SF 2415, allowed this financial literacy course to fulfill part of Iowa’s existing graduation requirements for social studies. A third measure, SF 139 of 2019, called for the new requirement to take effect with the class of 2021.

As the 2023 legislative session began, however, constituent concerns led to the filing and eventual signing of SF 391. This measure allows personal finance literacy content to be delivered though either a dedicated unit of coursework or its integration into other courses.

“This [request for change] actually came from the governor’s office,” says bill author Sen. Tim Kraayenbrink, who also sponsored SF 2415 in 2018.

“They were in contact with a lot of the smaller rural schools that were struggling not only to get teachers to teach the individual [financial] literacy courses — along with a lot of other courses — but also just the time … to be able to do it.”

Kraayenbrink stresses he is still a proponent of financial literacy education and that this change simply gives schools more flexibility.

“If [schools] feel like they’re getting good results and they have the instructor there and the class time to do it, then of course our number one ask is for them to continue on,” he says.

Finding outside partners, sustainable funding

Public-private partnerships can help fill instructional needs for schools struggling to find teachers or training opportunities.

“Organizations like [ours] and others are out there providing professional development for educators so that they have the competency and the capability,” Caltabiano says.

Ballweg notes that even before she filed AB 109, Milwaukee Public Schools was getting nearly $500,000 from Next Gen Personal Finance to implement financial literacy instruction.

“It’s not just that [Next Gen is] providing some funding for the schools to put this in their curriculum, but they’re also supporting the educators that are going to be doing the curriculum,” she says.

To some lawmakers, though, the real challenge is securing permanent funding.

“I used to work for a national nonprofit that worked directly with public schools, and I also know what happens when those partners go away,” Wisconsin Rep. Kristina Shelton said in a hearing on AB 109.

Early in the 2023-2025 state budget process, Gov. Tony Evers and the state superintendent of public instruction proposed allotting $5 million for a “Do the Math” initiative.

Under this program, which was not included in the final budget, the state would have provided resources to local school districts “to start or improve financial literacy curriculum” and “to develop a regional support network that includes professional development for educators and a model curriculum/scope and sequence for districts to implement.”

The post More states are requiring instruction in financial literacy for graduation; among the challenges is building up a trained teacher workforce appeared first on CSG Midwest.