Innovation in workforce policy and development is the focus of the 2024 Midwestern Legislative Chair’s Initiative of Ohio Sen. Bill Reineke (pictured to the right). In support of the initiative, CSG Midwest is producing a series of articles, research briefs and policy sessions for the region’s legislators on this initiative.

Innovation in workforce policy and development is the focus of the 2024 Midwestern Legislative Chair’s Initiative of Ohio Sen. Bill Reineke (pictured to the right). In support of the initiative, CSG Midwest is producing a series of articles, research briefs and policy sessions for the region’s legislators on this initiative.

Below, we explore the State of the State addresses delivered by Midwestern governors in early 2024 and focus on their ideas for building talent pipelines and addressing workforce shortages. We look at four common policy strategies:

- Boost rates of postsecondary attainment

- Expand the reach of apprenticeship programs

- Address the child care needs of families

- Recruit out-of-state workers

Strategy #1: Boost rates of postsecondary attainment

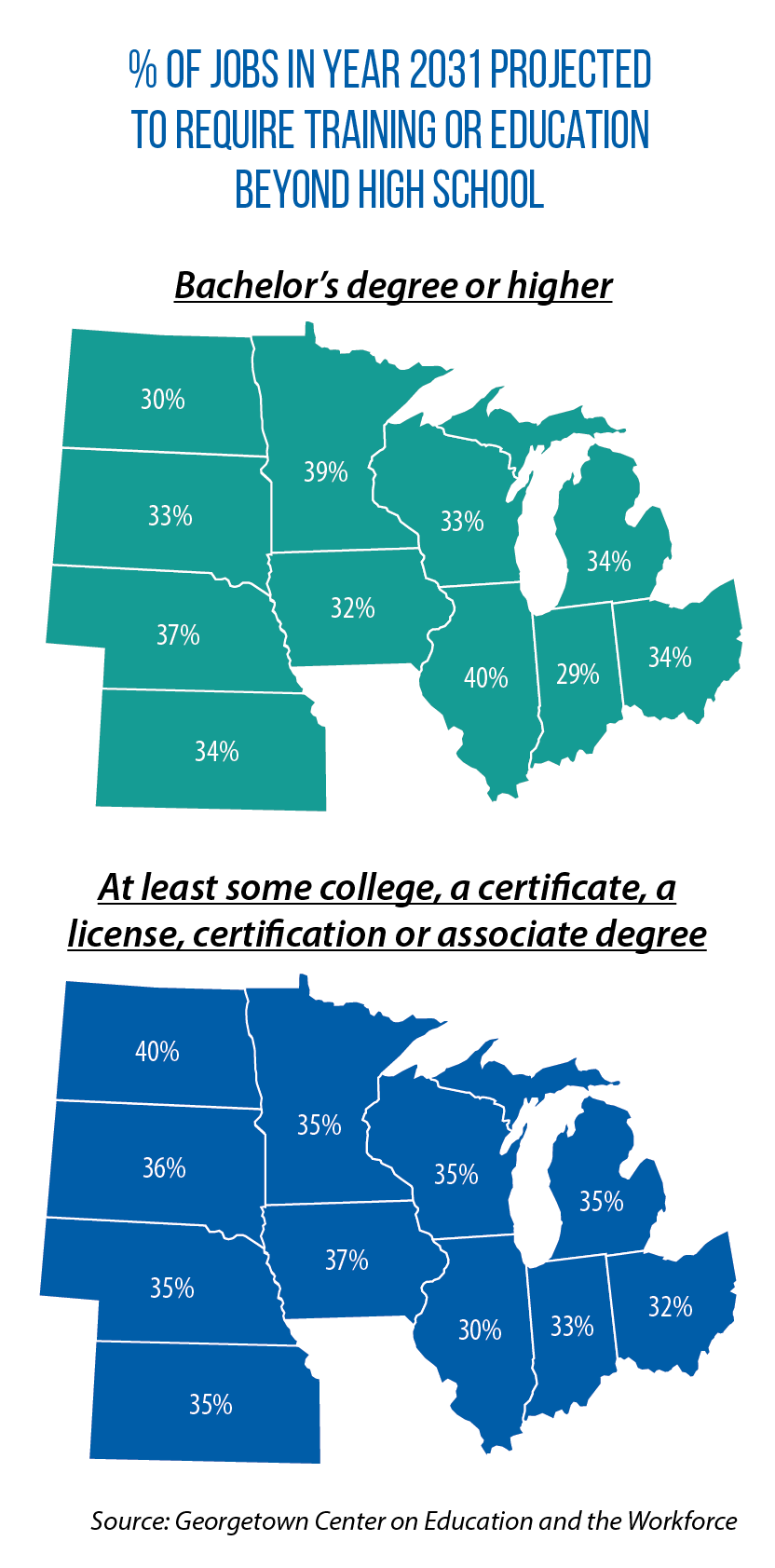

More jobs are requiring some postsecondary education and training beyond high school, a workforce reality noted in several of the governors’ recent speeches and proposals.

More jobs are requiring some postsecondary education and training beyond high school, a workforce reality noted in several of the governors’ recent speeches and proposals.

In Michigan, Gov. Gretchen Whitmer wants to make the first two years of community college tuition-free for every high school graduate. For students, she said, the plan would open new opportunities to pursue better-paying jobs. But Whitmer also noted that the state and its businesses will benefit from a larger pool of postsecondary-trained workers.

“As more supply chains come home and advanced manufacturing businesses expand in Michigan, they will need qualified talent,” she said. The state’s goal is to have 60 percent of working-age adults with a college degree or postsecondary skill certificate by 2030.

Six years ago, Iowa lawmakers set this statewide target: by 2025, 70 percent of the workforce should have education and training beyond high school. To get there, new programs were established and funded under the Future Ready Act (HB 2458 of 2018). For instance, a last-dollar scholarship has been made available to students pursuing degrees or certificates in high-need occupations. In fiscal year 2023, a total of $24 million went to nearly 10,000 Iowans. An associate degree in nursing was the most common occupation being pursued.

In her January 2024 address, Gov. Kim Reynolds reported to legislators that the state had reached its 70 percent goal ahead of schedule.

“Future Ready Iowa was born in this building with an executive order and bipartisan legislation; we set the vision and laid the foundation,” she said. “But elected leaders aren’t the ones who got it done. It was the people of Iowa … who created a new culture, merging the worlds of work and education like never before.”

At the start of Indiana’s 2024 session, Indiana Gov. Eric Holcomb challenged education and policy leaders to find new ways of making college more accessible. Among his ideas: create more degree options. Under SB 8, every public university would need to offer at least one three-year degree program, as well as study the feasibility of offering associate degrees to students.

Strategy #2: Expand reach of state-supported apprenticeship programs

Another feature of Iowa’s Future Ready initiative has been to invest more in registered apprenticeships — “earn and learn” programs for people to get paid while receiving on-the-job training and skills. Part of Iowa’s strategy has been developing and expanding new apprenticeships in high-demand fields. (The state’s Workforce Development Board identifies the high-demand fields).

Another feature of Iowa’s Future Ready initiative has been to invest more in registered apprenticeships — “earn and learn” programs for people to get paid while receiving on-the-job training and skills. Part of Iowa’s strategy has been developing and expanding new apprenticeships in high-demand fields. (The state’s Workforce Development Board identifies the high-demand fields).

One of Reynolds’ policy goals for 2024 is to expand high school students’ access to apprenticeships or other work-based learning opportunities (internships, job shadowing, etc.) in targeted industries.

In her 2024 State of the State address, South Dakota Gov. Kristi Noem highlighted the impact of recent investments in apprenticeships, including a new three-year, $7.9 million grant program. With that money, apprenticeship sponsors are eligible for up to $15,000 in funding support as well as state technical assistance.

“In just the first two quarters since launching the expanded effort, we’ve more than doubled the amount of new apprenticeships,” Noem said.

Raising awareness about apprenticeships and other worker training programs is the goal of Indiana’s One Stop to Start, a new web resource highlighted by Holcomb during his State of the State address. The “one stop” resource highlights high-growth industries in Indiana and includes a listing of state-supported education and training opportunities. Additionally, individuals can get connected with a career navigator to explore potential options.

In Ohio, Gov. Mike DeWine called for a statutory change requiring every high school student to have a career plan upon graduation from the the state’s K-12 system. “The [current] law fails to require maybe the most important thing — a plan for students to find a career they love and can excel at after graduation,” he said.

He also hailed recent state-level investments in career technical education, including $200 million in grants for new or expanded classrooms and more than $67 million to pay for new equipment in career tech programs.

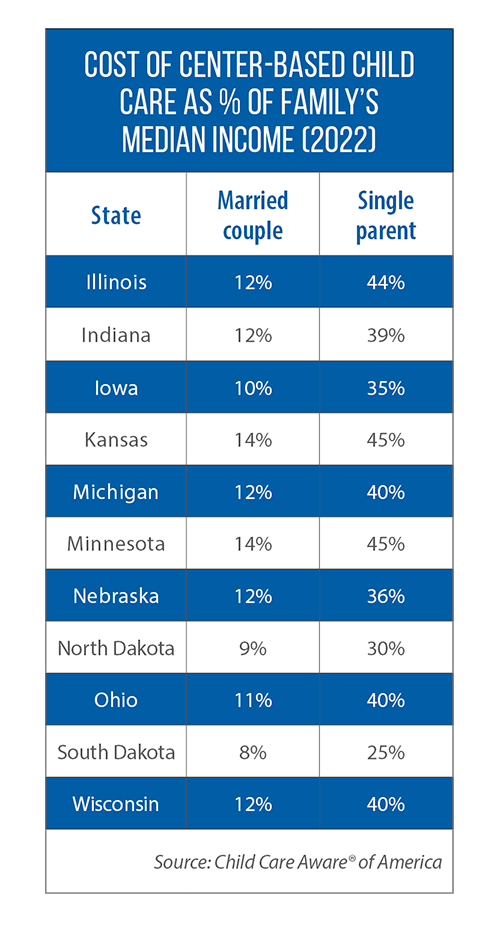

Strategy #3: Address the child care needs of families

In Kansas, more than half of the families in search of child care cannot find an open slot, Gov. Laura Kelly said to legislators in January. “[It’s] forcing many parents to quit their jobs, and the shortages are worst in our rural areas.”

Her proposed budget includes $56 million for child care. More than half of this money would be used to build up Kansas’ child care infrastructure — grants to build new facilities or expand existing operations. Local and private dollars match the state-level support.

Kelly also proposed one-time funding of $5 million for a public-private partnership in a 26-county region of northwest Kansas. Combined with private dollars and the support of local foundations, the state dollars would create a new endowment, a sustainable source of funding to add child care slots in this region’s mostly rural communities. If successful, the approach could be replicated in other parts of Kansas.

Nebraska Gov. Jim Pillen has proposed building a “micro-center” network of child care programs.

This model aims to remove some of the common infrastructure and operational obstacles faced by smaller-sized, family-based child care providers — for example, a lack of space to expand capacity in their homes or a lack of capital to build a stand-alone center.

This model aims to remove some of the common infrastructure and operational obstacles faced by smaller-sized, family-based child care providers — for example, a lack of space to expand capacity in their homes or a lack of capital to build a stand-alone center.

Here is how it works: Smaller providers get low- or no-cost space to deliver care in a few rooms of an existing facility (a school or business in the community, for example). These smaller providers also then get administrative and technical support from a shared, outside entity.

Nebraska’s LB 1416 would establish a state grant program to pursue the micro-center model.

In Illinois. Gov. J.B. Pritzker told legislators in February that with continuing state investments for an initiative known as “Smart Start,” universal preschool for 3- and 4-year-olds could be achieved by 2027. Last year’s Illinois budget included $300 million in new funding for child care and early-childhood education. With those additional dollars, the state is

- providing grants to schools and nonprofit operators to create more child care slots and for private operators to expand operations;

- investing in programs that raise the wages of workers in this sector and that create new scholarship and apprenticeship programs; and

- expanding the availability of child care assistance for lower-income families.

“Smart Start is having the desired benefit for working parents and their children,” Pritzker said. “Child care utilization rates are higher than ever before.”

Last year, North Dakota legislators took steps to expand child care capacity, and Gov. Doug Burgum hailed that $66 million investment in his 2024 State of the State address. As part of the enacted legislation (HB 1540), more families became eligible for state-funded child care assistance, providers are being paid at higher rates, and employers are getting incentives to cover part of their workers’ child care expenses.

“What’s happening with that investment, now more than 4,800 working families have received help with child care costs just in the first six months of this biennium; more than 300 child care business have benefited from grants and incentives,” Burgum said. “Think of that, close to 5,000. When we talk about trying to solve our issue with 30,000 jobs open, we put a huge dent in it … because we got 5,000 people that maybe came back into the

workforce.”

Wisconsin Gov. Tony Evers told legislators in January that a child care crisis is imminent minus state action; public funding is needed to keep many centers open, he said. Like other Midwestern governors, too, Evers linked the lack of child care availability to a shortage of workers.

“From my vantage point, three things are key to addressing our state’s workforce challenges: First, we must find a long-term solution to our state’s looming child care crisis; second, we must expand paid family leave; and third, we must invest in public education at every level, from early childhood to our technical colleges and universities.”

On that second priority, Evers has proposed a state investment of $240 million to jump-start a program that would ensure 12 weeks of paid family leave for most private-sector employees.

Last year, Minnesota legislators established a state-run insurance program providing workers with up 20 weeks of family and medical leave and also created a first-in-the-Midwest Child Tax Credit.

In his 2024 State of the State address, Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz highlighted a new state biennial budget that includes expanded access to Early Learning Scholarships and Child Care Assistance programs as well as voluntary, publicly funded prekindergarten. Legislators also invested in higher pay for child care workers and higher compensation rates for providers.

“We’ve expanded access to pre-k and affordable child care,” Walz said in his address.

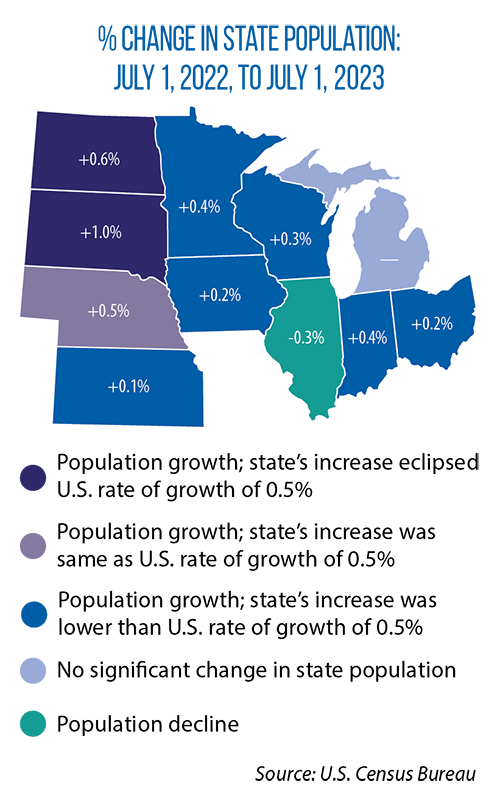

Strategy #4: Recruit new workers to the state

Pillen and Noem said part of their states’ strategies for alleviating workforce shortages should be to attract out-of-state talent.

Pillen and Noem said part of their states’ strategies for alleviating workforce shortages should be to attract out-of-state talent.

Pillen has proposed a new tax credit for employers who cover the relocation expenses of people who move to Nebraska for work (LB 1400). The credit is up to $5,000 per employee. The relocating worker must have an annual wage of between $70,000 and $250,000. That worker also would get a one-time income tax break.

“We must recognize that investing in the twenty-first century workforce is different from what we’ve done before,” Pillen said. “No longer can we focus tax breaks on companies that are takers, not givers, and that do not share our values.

In June 2023, South Dakota launched “Freedom Works Here,” a workforce-recruitment campaign with targeted ads for the state’s highest-demand professions — for example, electricians, plumbers, welders, accountants and nurses. This campaign, combined with recent statutory changes that recognize out-of-state professional licenses, has led to more job applicants and a year-over-year increase of 10,000 people in the labor force, Noem said.

“This is indisputably the most impactful workforce campaign in South Dakota’s history,” she added.

The post 2024 MLC Chair’s Initiative on Workforce | Governors tout successes, new policies to build talent pipelines appeared first on CSG Midwest.