Within the many recognizable branches of the military are a multitude of ways to serve with which many Americans may not be familiar. Each of the six branches of the armed forces falls under one of three departments: the Navy, Army or Air Force.

Continue readingArtificial Intelligence in the States: Emerging Legislation

Since 2019, 17 states have enacted 29 bills focused on regulating the design, development and use of artificial intelligence. These bills primarily address two regulatory concerns: data privacy and accountability. Legislatures in California, Colorado and Virginia have led the way in establishing regulatory and compliance frameworks for AI systems.

Continue readingArtificial Intelligence in the States: Challenges and Guiding Principles for State Leaders

For years now, the use of artificial intelligence has been ingrained into the everyday lives of Americans through iPhones, social media and even email platforms. A 2018 study by OpenAI revealed the amount of computational power used for AI training has doubled every year since 2012. Due to AI’s rapid advancement, state policymakers must determine how their states must address the significant regulatory challenges posed by AI.

Continue readingArtificial Intelligence in the States: Harnessing the Power of AI in the Public Sector

As AI systems advance, concerns grow regarding the safety and effectiveness of these tools as well as the potential impacts of these systems on the workforce and the economy. Although private sector uses of AI garner much attention, these systems are also used by the public sector to streamline service provision and support public officials in fields such as law enforcement, elections, transportation, public finance and government administration.

Continue readingHow Ballot Measures Get on the Ballot

When voters take to the polls, they not only vote on political candidates, but also ballot measures. Most voters know where they stand on these measures, but how much thought is given to how they made it onto the ballot in the first place? To answer this question, one must first define a ballot measure. A ballot measure is a proposed law, issue, constitutional amendment or question that appears on a statewide or local ballot for voters of the jurisdiction to vote on.

Continue readingWhat is a Caucus?

Caucuses are rarely a topic of everyday conversation; however, they play an essential role in shaping the American government. The American use of the term “caucus” was first used in 18th century Boston to refer to a political club. Over time, the term evolved, referring to two distinct forms of political organization – party caucuses and legislative caucuses. These forms are distinct in membership and purpose. However, both allow Americans to come together around common political objectives.

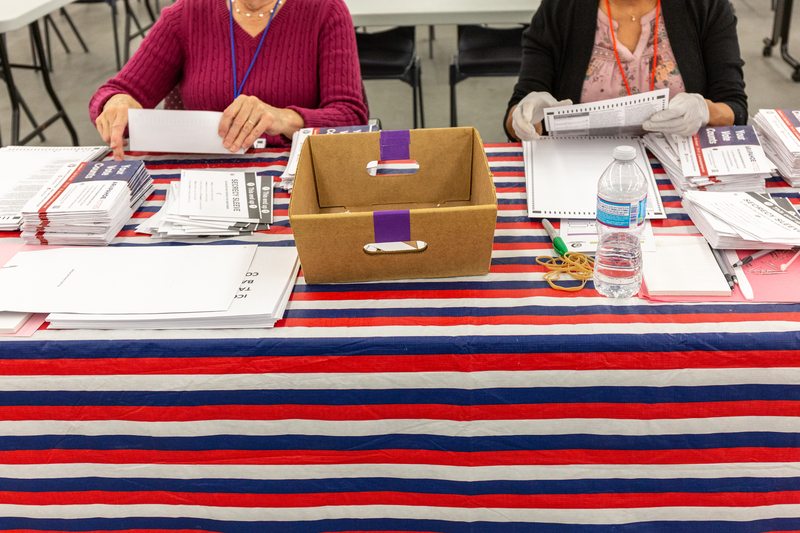

Continue readingAbsentee Ballot Processing in the States

During the 2020 general election, a surge of Americans elected to vote via absentee ballot. Now, almost three years later, many Americans can still recall the days-long wait for the race to be called. Polls had long been closed, but ballots were still being counted. Why?

Continue readingElection Technology Through the Years

When going to vote, most people do not think about the technology behind the equipment they are using. They wait in line, show their ID, fill out their ballot, scan it into a machine, grab the free sticker and go about their day. Very little, if any, thought is given to how we got here. With questions looming about election integrity and election technology systems, it is important to understand the election technology we have today.

Continue readingExecutive Branch Contests Highlight Election Day 2023

General elections for governor, justice, and state House and Senate occur across six states Tuesday, highlighting notable Election Day 2023 contests. In an additional seven states, ballot measures are up for vote that address areas ranging from election spending and property taxes to project funding.

Continue readingState Measures to Improve Election Security and Voter Confidence

By Nicholas Relich and Casandra Hockenberry

State officials and lawmakers across the US have proposed and passed laws to increase the confidence of voters in election integrity. Challenges faced in the last several elections — such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the spread of misinformation — served as a starting point for some of this legislation.

Post-election audits, known as PEAs, serve as safeguard against errors or fraud and verify of accuracy. Many states have existing statutes authorizing or mandating PEAs in one of two forms: traditional audits or risk-limiting audits. A traditional audit looks at a fixed percentage of voting districts or voting machines and compares the paper record to the results produced by the voting system. A risk-limiting audit is a statistically based audit designed to reduce the risk of a contested race being certified with the wrong winner. If an election margin is wider, fewer ballots must be reviewed; if there is a narrow margin more ballots are reviewed.

For states with existing statutes, the scope (how many ballots) and method (determining precincts, timing, technology and type of audit) may be reconsidered for future elections. In 2022, Louisiana and Maine passed bills mandating audits in the coming elections. Louisiana passed HB 924 (2022) that will require traditional audits, beginning in 2023 after “the procurement and implementation of a new voting system by the secretary of state.” Similar legislation in Maine will pilot a risk-limiting audit after the 2024 election and will allow similar audits statewide beginning the following year.

Election officials must navigate privacy and accuracy concerns in voter registration databases, fight social media misinformation and disinformation, and work to ensure the security of voting infrastructure. States, often in partnership with federal cybersecurity and election agencies —such as the U.S. Department of Defense Federal Voting Assistance Program, U.S. Department of Homeland Security Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, and the U.S. Election Assistance Program — have sought numerous solutions to these issues to improve election security and voter’s perception of the trustworthiness in elections in the digital age.

Voter Registration Data

Voter registration data from states, including information on voter names, address and demographic information, have long been available for private use, at various degrees of accessibility, as a means to promote transparency in the election process. However, in an era of increased concern for data privacy, states have adopted different policies regarding the openness of this information. Some states restrict data requests to government agencies and election campaigns, while others maintain open access to the public at large. Many states also charge fees to obtain voter data. States also keep certain information confidential, such as a voter’s social security number, date of birth and driver’s license number, though these policies vary by state. States also restrict information for participants of address confidentiality programs, which protects the confidentiality of victims of certain violent crimes.

Voter registration data is a critical tool for election officials to maintain accurate voter rolls despite changes to an individual voter’s status, such as when a voter moves within the state but into a new election district or across state lines. This in turn helps officials maintain and build public trust in the election process. In May 2023, Washington enacted WA S5459, which requires any requests for voter registration data be processed by the secretary of state, with the goal of increasing public confidence through a more efficient and streamlined process. In the 2023 legislative sessions, Arkansas and South Dakota also provided additional directives for their Secretaries of State to update these records.

Misinformation and Disinformation

Ensuring voters have accurate information on polling locations, procedures, and election issues and have confidence in the election results is a critical goal for states. Social media provides election agencies a means of communicating important resources to voters, but these platforms also provide foreign and domestic bad actors an opportunity to promote confusion and distrust. To counter misinformation and disinformation online, secretaries of state around the nation have taken part in the #TrustedInfo Initiative, a public education campaign led by the National Association of Secretaries of State In 2007, the Election Assistance Commission established the Voluntary Voting System Guidelines, a set of recommendations which set a standard for the agency’s evaluation of voting systems and assists election officials in their own planning. States have either adopted the Election Assistance Commission’s guidelines as their own via statute or created their own testing and certification guidelines. The Commission recently updated this guidance with the VVSG 2.0, which will go into effect on November 16, 2023, after many of this year’s elections. The Election Assistance Commission clarified that the new standards do not invalidate election technologies approved under previous guidelines, but rather reflect updated systems and goals that election officials should consider implementing in the future. At the time of publishing, no election technology vendor has completed the VVSG 2.0 certification processes. State officials recognize the need to mitigate potential confusion in voters through clear communication of implications of the new guidelines.

Several states enacted legislation relating to the cybersecurity of voting infrastructure in 2023. Wyoming and Alabama passed laws requiring electronic voting systems to be incapable of connecting to the internet. States also focused on the use and procedures surrounding paper ballots. Alabama requires the use of paper ballots in electronic vote counting systems through AL S9 (2023). Arkansas required counties cover the cost of paper ballots should they chose to use them over voting machines and ensured that if paper ballots are used, they be compatible with electronic vote tabulation devices selected by the Secretary of State. States have also been interested in the standards and testing of voting infrastructure. South Dakota required that election officials conduct a public test of automatic vote tabulating equipment to ensure accurate vote counting, and Wyoming requires every electronic voting system used in the state include proof of certification by the United States Election Assistance Commission and approval from the Secretary of State.

Summary

Legislation on elections walks a fine line between improving security and ensuring access for all voters. Cybersecurity continues to be an important consideration for state officials motivated to ensure positive voter perception of election integrity. Americans’ confidence in election administration and the legitimacy of election results is a top priority of state officials. This means increased transparency with how elections are administered in the U.S. are necessary.