Flexible academic tracks. Early exposure to the workforce. Financial support for students pursuing work-based learning opportunities. Transitional learning programs that extend beyond secondary education.

Rep. Bob Behning has seen how those education models work in other countries (the Swiss vocational model, for instance).

Among his goals with the recently signed HB 1002: Use lessons learned from those systems to reinvent the high school experience for students in his home state of Indiana, in a way that makes learning more impactful and gets them career-ready.

“A lot of kids see little value, and are finding less and less relevancy, in high school,” says Behning, a chief sponsor of the legislation.

“A bill like HB 1002 changes the paradigm. It provides the academics [that students] need, but embeds it in a work-based learning experience.”

New Career Scholarship Accounts for students

Central to Indiana’s reinvention plan is the creation of new career scholarship accounts, or CSAs.

With the new law in place, participating students will be allotted up to $5,000 each for the costs associated with career education — for example, enrollment in a youth apprenticeship program, career coaching services, community college coursework, certification examinations, and transportation to and from job-training locations.

A total of $15 million will go to CSAs over the next two fiscal years.

Students who choose an apprenticeship track will be paid by their employer. The amount of time a student spends off campus in a CSA-funded program will vary.

“If you look at what we would consider a traditional youth apprenticeship, you’re probably looking at starting in your junior year where you may spend one to two days [a week] at an employer,” Behning explains.

“By the time you’re a senior, you could spend two to three [days], and by the time you’re the equivalent of what would be a freshman in college, it could be up to three to four days.”

To accommodate these students’ unique school schedules, the state Board of Education will establish a new path for a high school diploma that aligns with a work-based learning model.

Another key component of HB 1002: ensuring that younger K-12 students are aware of and prepared for the new training opportunities.

By the end of this year, state education leaders will develop new standards for a “career awareness course” that introduces students to the CSA program. The course also will show students which industry sectors are in high demand, identify the education and workforce training prerequisites needed to enter various fields, and offer individualized career-plan counseling.

Schools will be required to offer this career awareness course to ninth-graders by 2030.

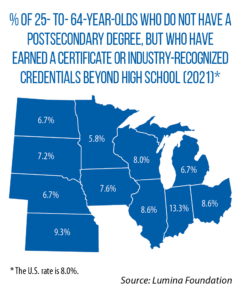

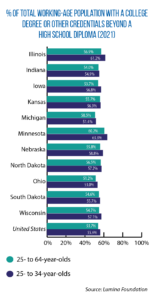

Goal: More students earn a workforce credential

In order to qualify as a CSA program, the work-based experience must culminate in a student earning a credential — for example, an associate degree or an industry-recognized certificate.

For each student who successfully earns a credential, a $500 grant will be awarded to his or her school as well as the CSA-participating entity (a business or career-and-technical education center, for example).

“Today, the credential really is your currency in the labor market,” says Jason Bearce, vice president of education and workforce development for the Indiana Chamber of Commerce and a proponent of HB 1002.

“Employers do a lot of training. A fair amount of it doesn’t result in any kind of recognized certificate or industry credential that would be recognized outside of that place of business. We think that’s a missed opportunity [for workers].”

Bearce also says an increase in credential attainment can have broader, positive economic effects.

“At one time, competing for a business expansion or relocation was primarily about, What’s the tax incentive package? What’s the regulatory environment? What’s the cost of doing business?” Bearce says.

Today, though, site selection often hinges on this question: “Who has a critical mass of highly skilled human capital?”

A highly credentialed workforce helps make the case.

Concerns about potential for ‘new patronage’

How will the state locate and secure work-based learning and training opportunities for potentially thousands of students?

HB 1002 outlines a role for “intermediaries.”

“[They are] the facilitator that brings the employer and the student together,” Behning explains.

“It can be a not-for-profit, it could be a for-profit, but it would be the group that’s in the middle that’s [an] aggregator of potential opportunities for kids.”

The state’s new budget includes $5 million for “intermediary capacity building” over the next fiscal year.

“We are giving some seed money to intermediaries,” Behning says. “Long term, the goal would be that they would be funded as a fee to employers for embedding an apprentice in your business.”

Opponents of HB 1002, such as Rep. Ed DeLaney, believe the administrative burden of operating the CSA program and funding of intermediaries will be exceedingly expensive.

And since qualified CSA programs must include a credential component, DeLaney says this new strategy will undercut the value of existing career-and-technical courses being offered in schools and could lead to decreases in school funding.

Additionally, although participating CSA employers must undergo a rigorous process to demonstrate the high value of their on-the-job training or apprenticeship offering, DeLaney is concerned the new law could lead to an unequal playing field that favors partisan alliances.

“I think it will benefit those businesses that are most adept at getting government grants,” DeLaney says. “To some extent, this does run the risk of being what I call the ‘new patronage.’ ”

During legislative debate over the measure, opponents and even some proponents of HB 1002 said a better plan of action would have been to begin the CSA program as a smaller, more targeted pilot initiative, or to phase in the new model with a small cohort of established intermediaries and employer partners.

Behning, who believes the need for comprehensive work-based learning for students is too imperative to wait for a pilot study, anticipates “a fairly slow uptake [to the CSA program] just because it’s a new concept rolling out.”

The post Indiana’s new career scholarship accounts will provide high school students with up to $5,000 to pursue work-based learning, credentials appeared first on CSG Midwest.

She lives in and represents a part of North Dakota’s coal country.

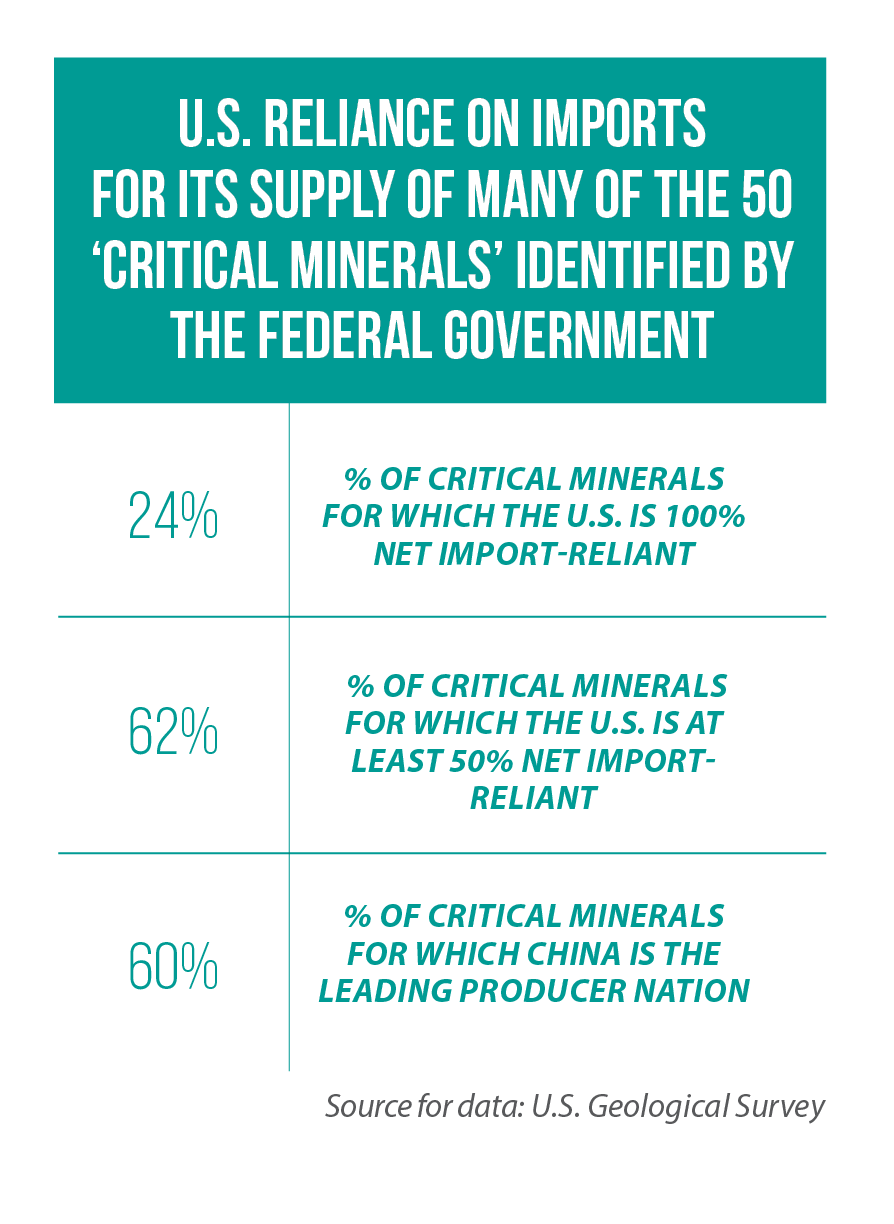

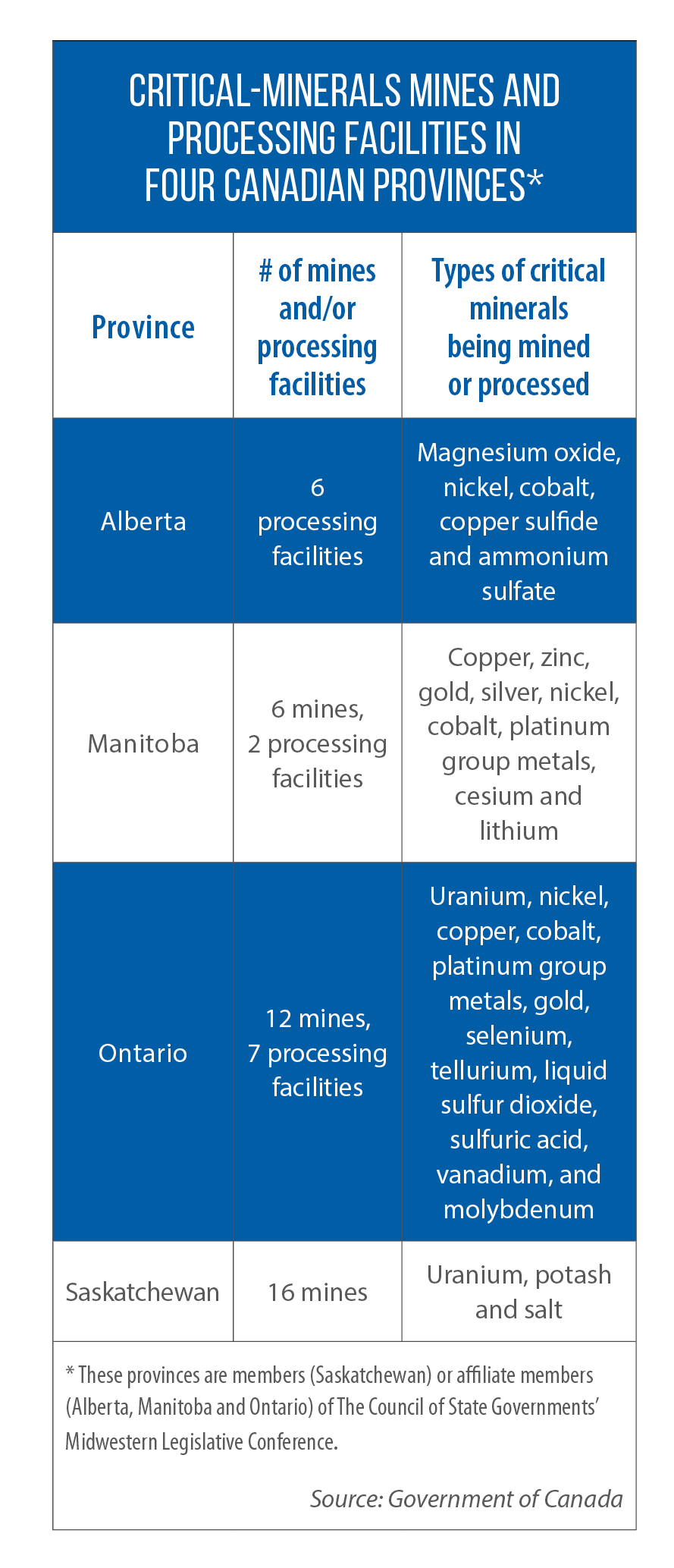

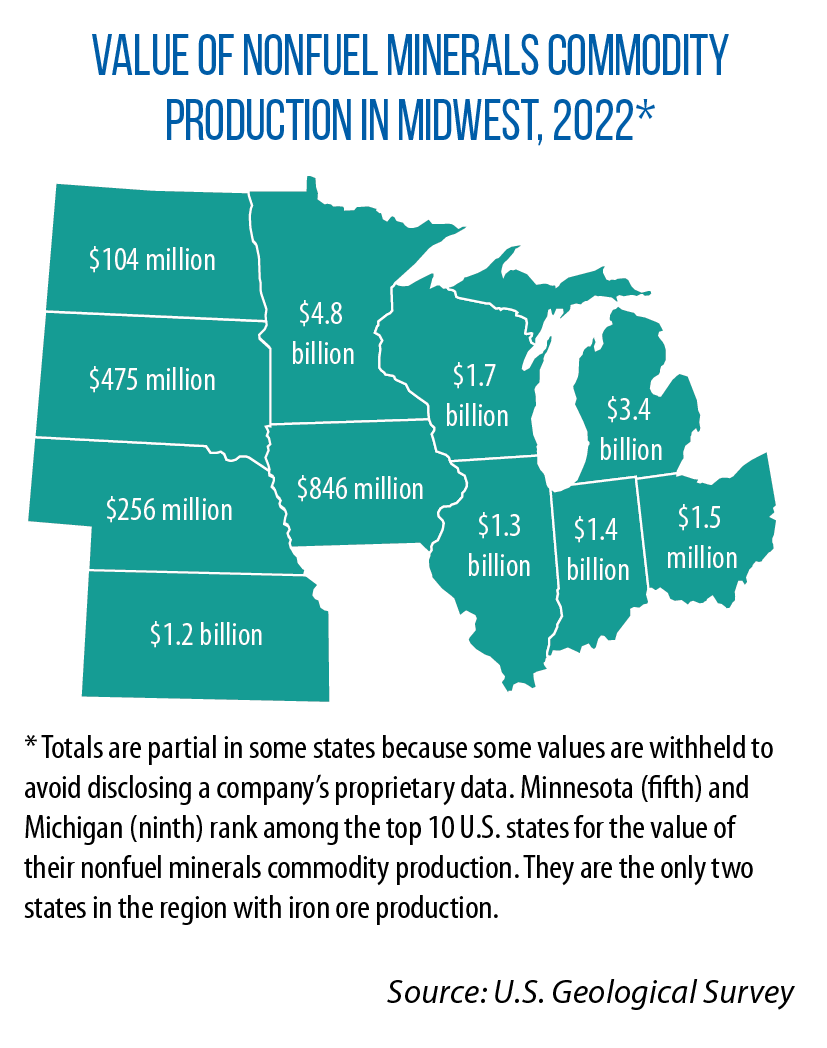

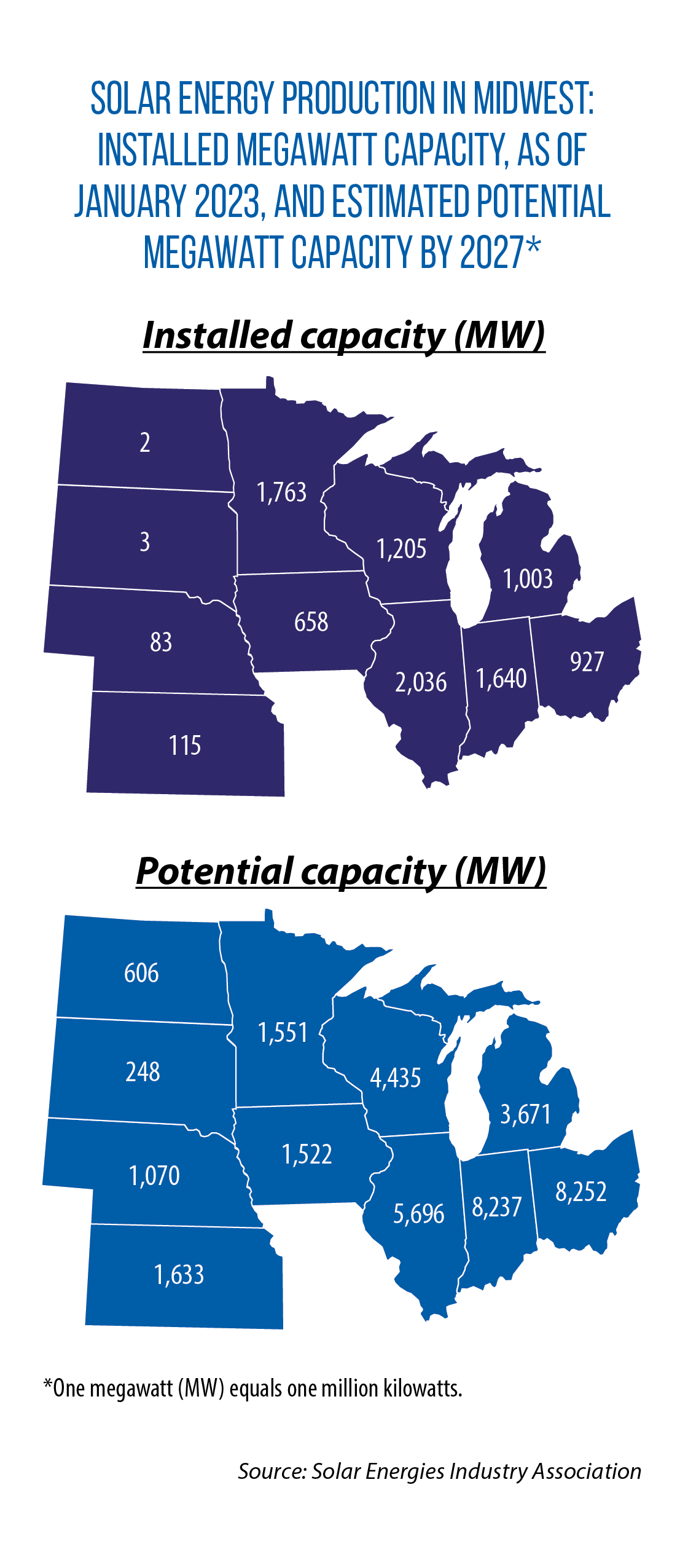

She lives in and represents a part of North Dakota’s coal country. Mineral resources, such as lithium, cobalt, nickel, and rare-earth elements are essential components of batteries, electric motors, and many other advanced technologies.

Mineral resources, such as lithium, cobalt, nickel, and rare-earth elements are essential components of batteries, electric motors, and many other advanced technologies. New federal laws, programs and investments also are in place to increase domestic production.

New federal laws, programs and investments also are in place to increase domestic production.

Rep. Kendell Culp grows corn and soybeans and raises beef cattle in a part of Indiana with some of the most productive agricultural land in the entire state.

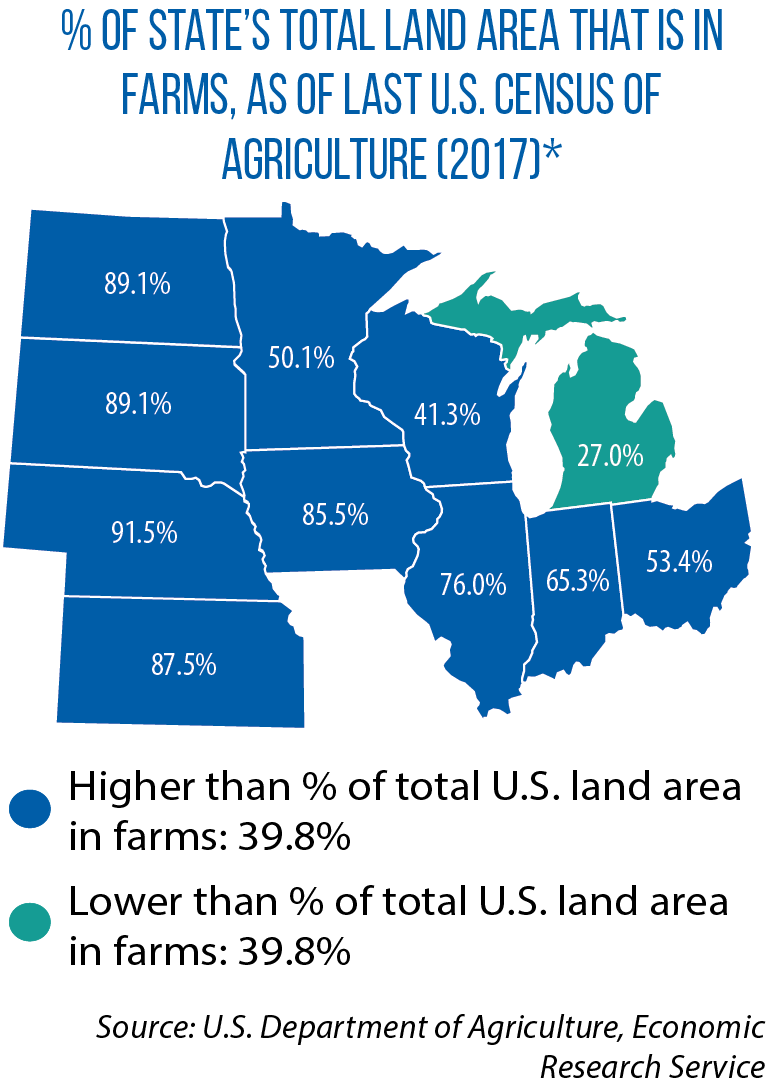

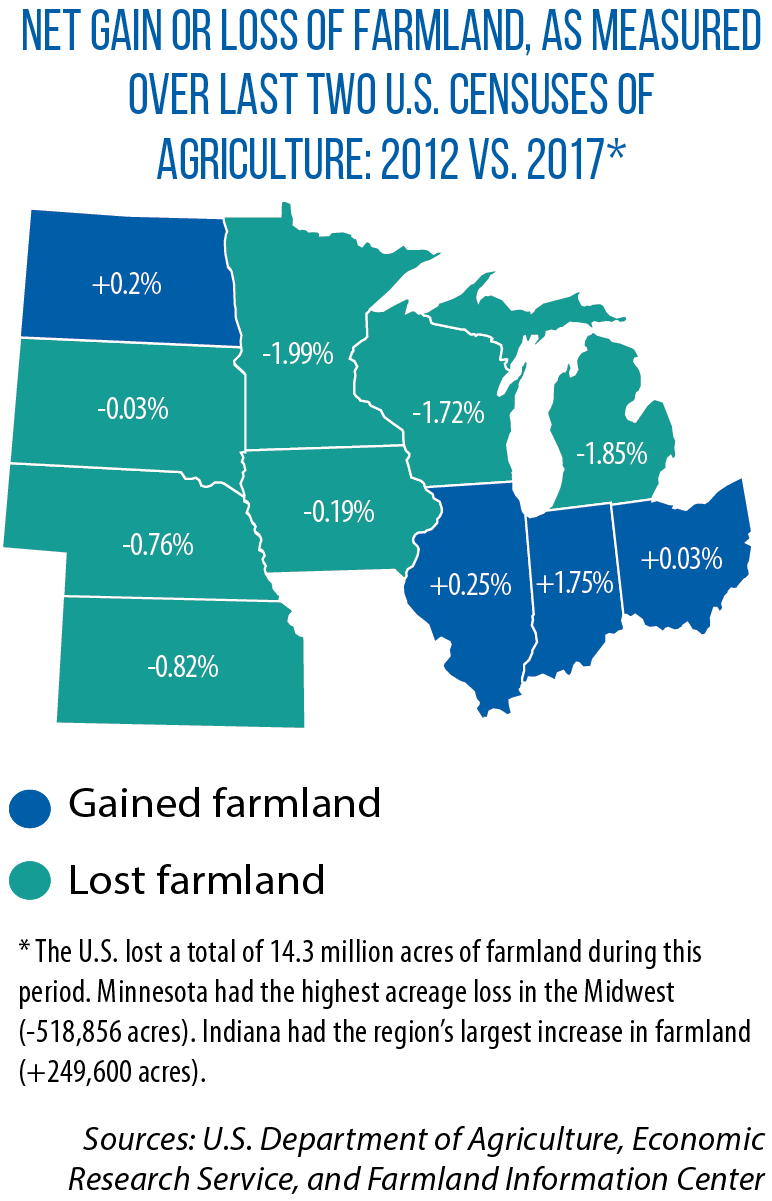

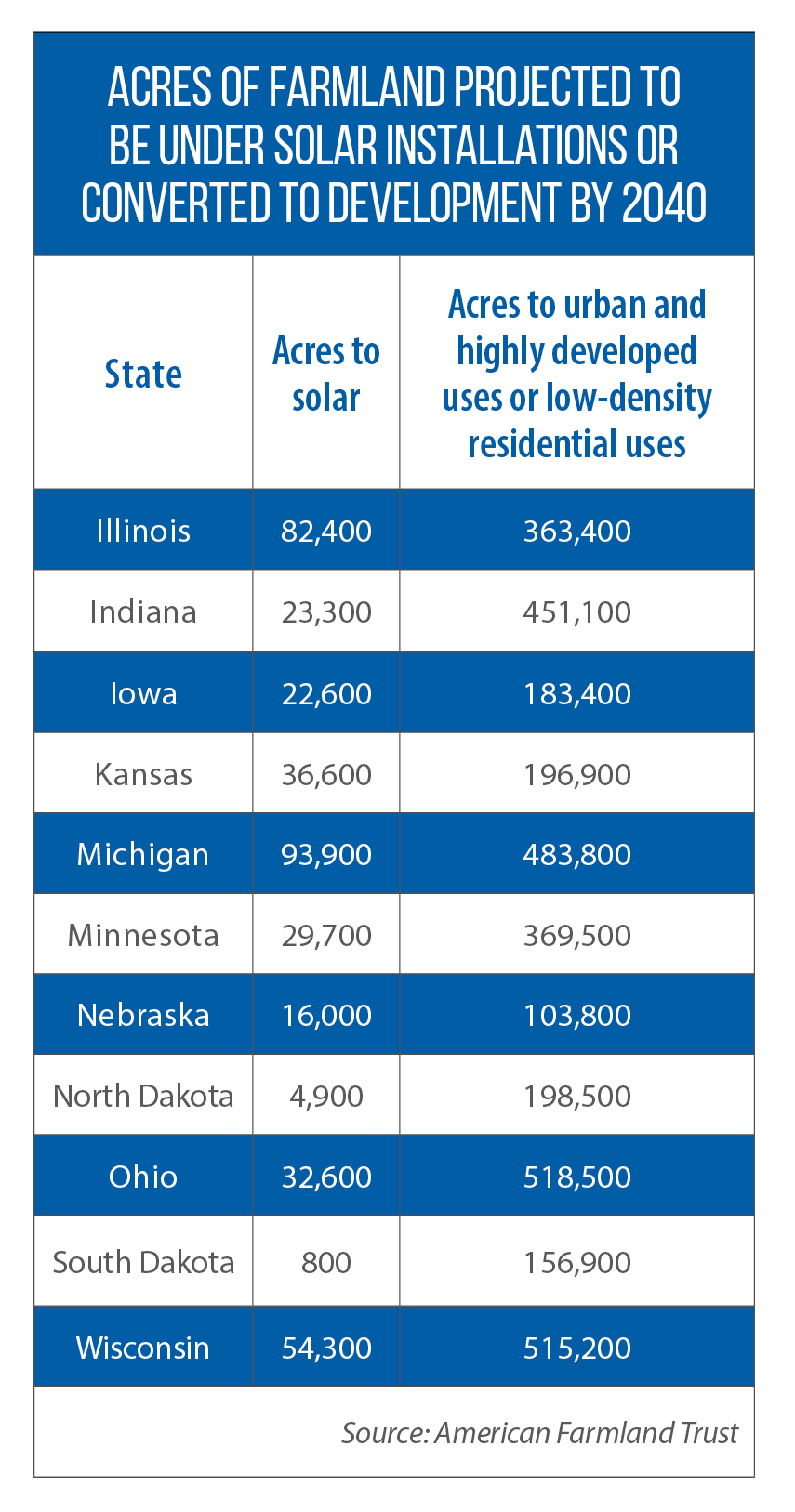

Rep. Kendell Culp grows corn and soybeans and raises beef cattle in a part of Indiana with some of the most productive agricultural land in the entire state. “Measuring the acres lost is important,” Culp says, “but just as important is what it’s being lost to.”

“Measuring the acres lost is important,” Culp says, “but just as important is what it’s being lost to.” However, many states in this region have lost some of this land to population changes, sprawl and development in recent decades. Looking ahead, it’s not just residential, commercial or industrial development in new areas that could replace farmland.

However, many states in this region have lost some of this land to population changes, sprawl and development in recent decades. Looking ahead, it’s not just residential, commercial or industrial development in new areas that could replace farmland. The pinch on agricultural land is being felt in Wisconsin as well. According to Sen. Patrick Testin, his state has lost nearly 1 million acres over the last two decades, and he worries about future declines due to pressures not just from other types of development or uses, but to some longstanding demographic and economic trends.

The pinch on agricultural land is being felt in Wisconsin as well. According to Sen. Patrick Testin, his state has lost nearly 1 million acres over the last two decades, and he worries about future declines due to pressures not just from other types of development or uses, but to some longstanding demographic and economic trends. “What we’re trying to do with this bill is encourage more people to participate, first of all, and then encourage more farmers to put more acreage into it,” says Wisconsin Rep. Katrina Shankland, another sponsor of the bill.

“What we’re trying to do with this bill is encourage more people to participate, first of all, and then encourage more farmers to put more acreage into it,” says Wisconsin Rep. Katrina Shankland, another sponsor of the bill. Under a PACE program, landowners are compensated for keeping their land for agricultural use; the compensation amount is based on the property’s fair market value.

Under a PACE program, landowners are compensated for keeping their land for agricultural use; the compensation amount is based on the property’s fair market value.

This year’s focus is “Climate Resiliency in Great Lakes Communities.” The institute began in late March with a

This year’s focus is “Climate Resiliency in Great Lakes Communities.” The institute began in late March with a