Rep. Kendell Culp grows corn and soybeans and raises beef cattle in a part of Indiana with some of the most productive agricultural land in the entire state.

Rep. Kendell Culp grows corn and soybeans and raises beef cattle in a part of Indiana with some of the most productive agricultural land in the entire state.

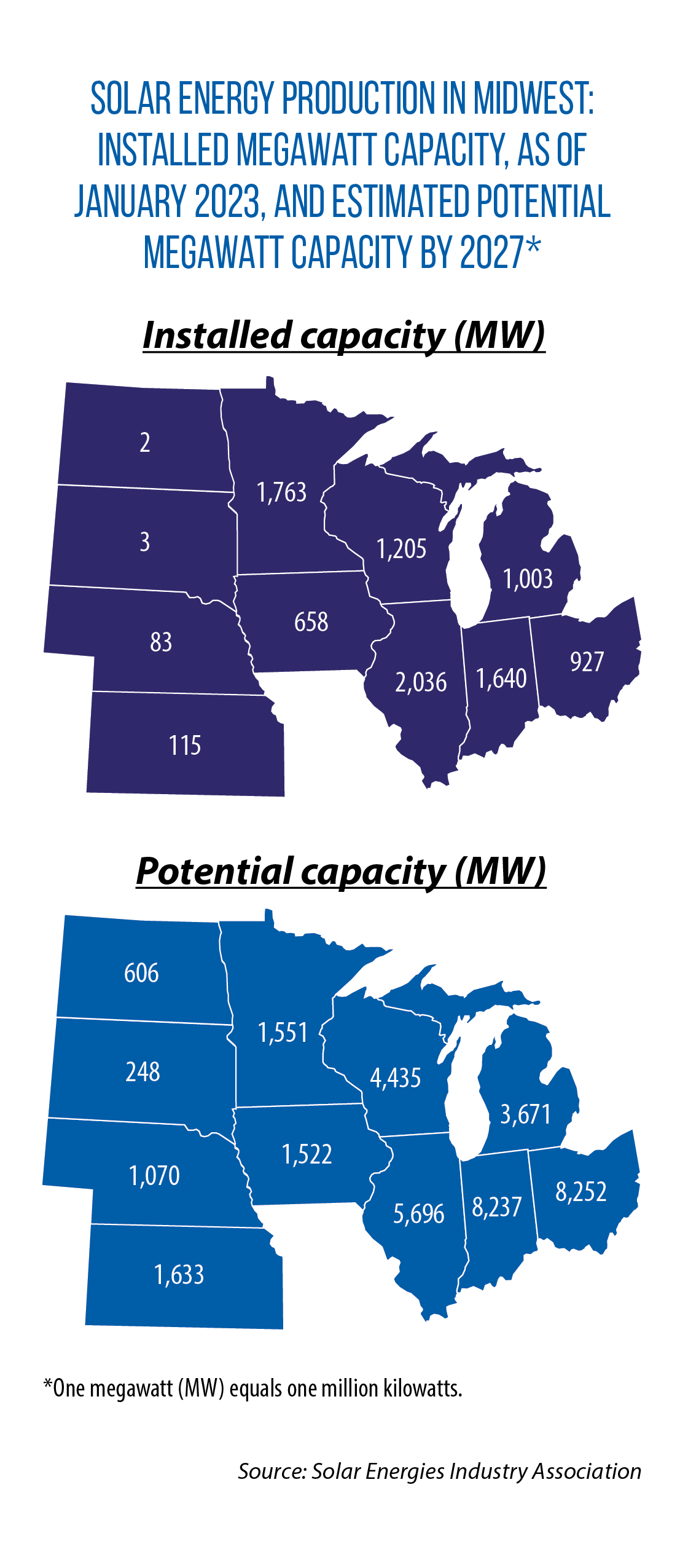

But some of that same land also has appeal as a site for other uses, particularly renewable energy projects such as solar farms that are growing in number.

“It is an issue on a lot of people’s minds right now,” Culp says about what he hears from constituents about the actual and potential loss of prime farmland. He heard it as a longtime county commissioner, and again when he did his first-ever survey as a newly elected state legislator in the fall.

His response was the introduction of two bills this year — both of which became law — that will have the state taking an in-depth look at trends in farmland loss and land use, as well as policy ideas to keep this land in agricultural production.

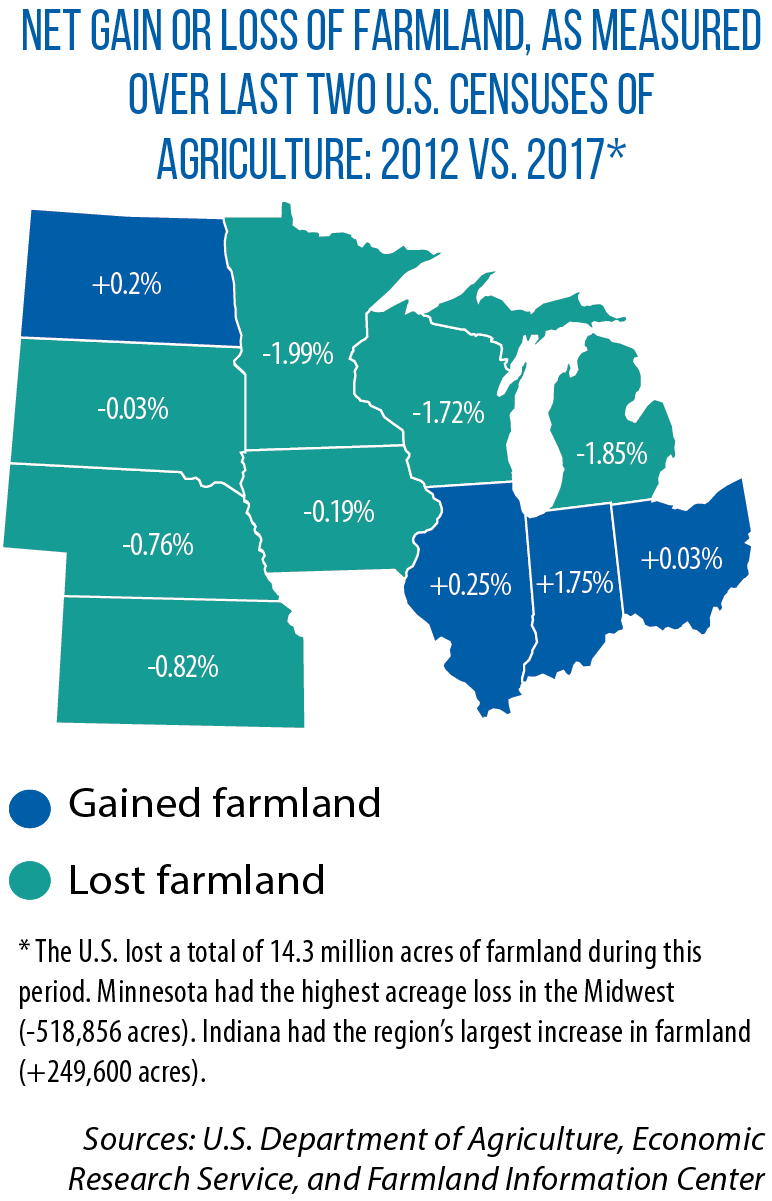

“Measuring the acres lost is important,” Culp says, “but just as important is what it’s being lost to.”

“Measuring the acres lost is important,” Culp says, “but just as important is what it’s being lost to.”

Those are the two goals of HB 1557, a new law that directs the Indiana Department of Agriculture to detail losses of farmland between 2010 and 2022. The second enacted measure, HB 1132, creates a state-level land use task force, a group of legislators and others who will look at growth patterns in Indiana’s rural, urban and suburban areas. Loss of farmland will be one focus of this task force. Another will be the extent of food insecurity in different parts of Indiana.

“There is the perception that the less farmland, the less food,” Culp says. “I don’t think that’s necessarily been the reality because farmers always have been able to use new technologies to maximize production. But I do think that the issue of food insecurity and lost farmland is something we need to be more conscious of, especially if more acres start getting taken out of production at drastic rates.

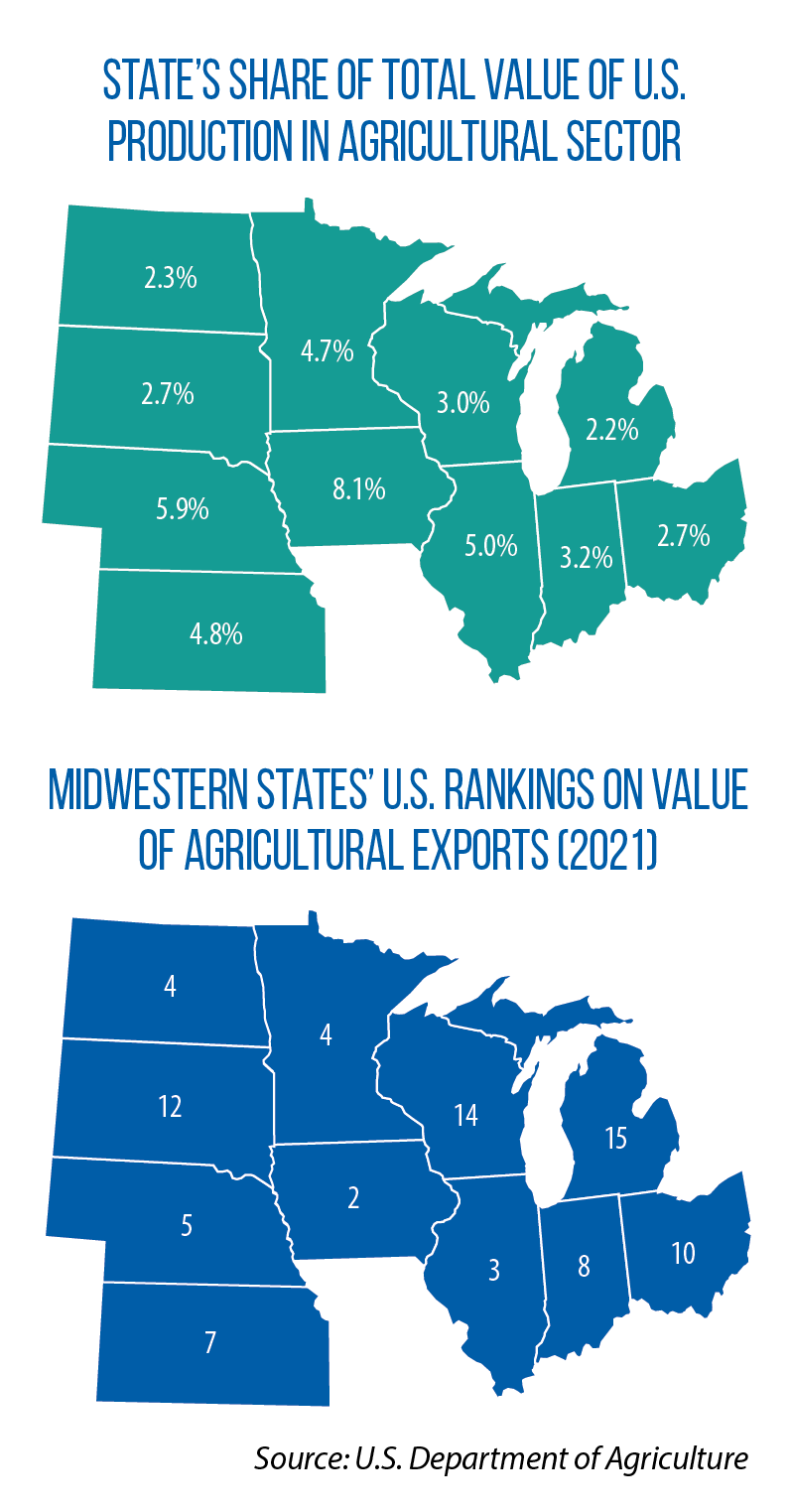

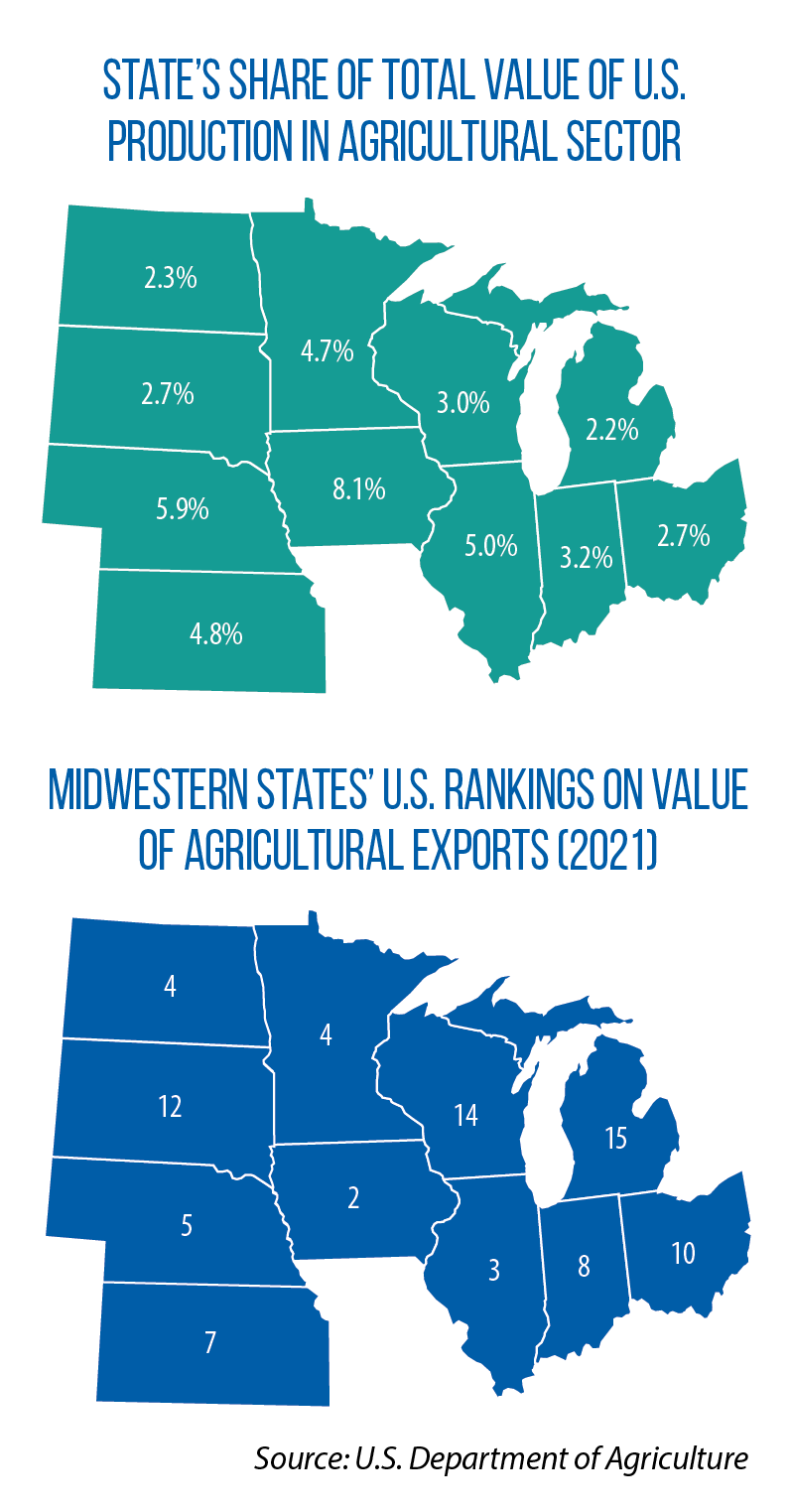

“It’s also a really great responsibility we have [to the world]. People in other countries think more than we do about where their food comes from, and they know they rely on the U.S., specifically the states of the Midwest.”

Future pressures and needs

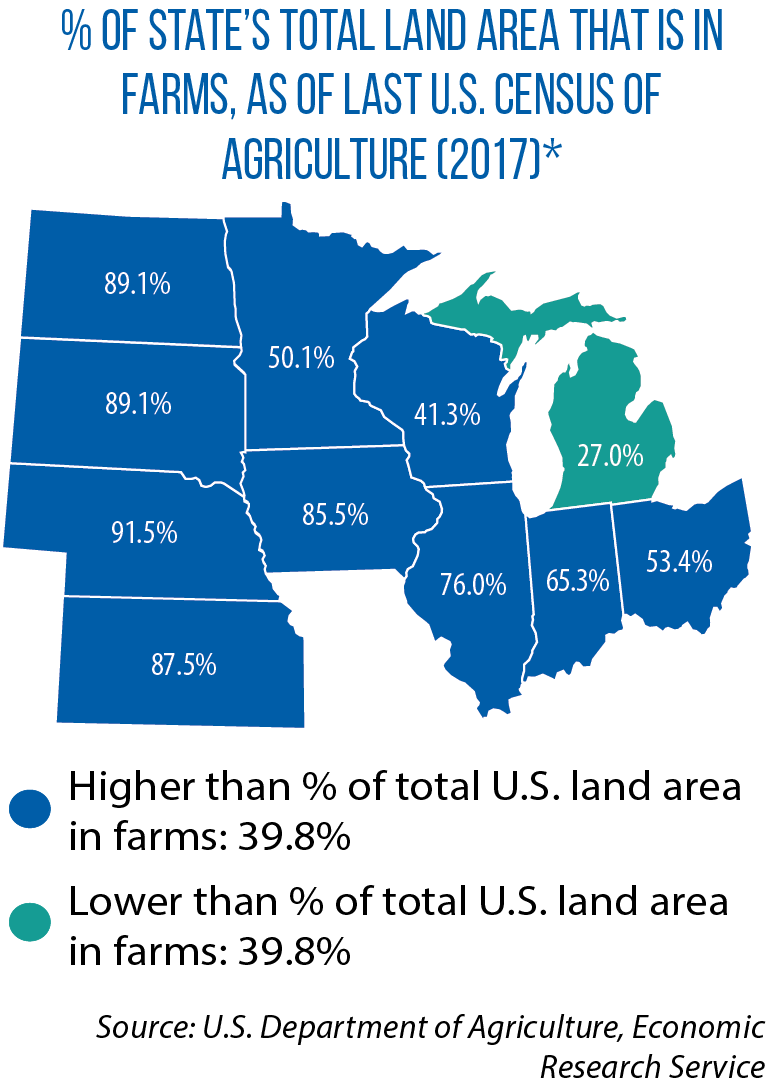

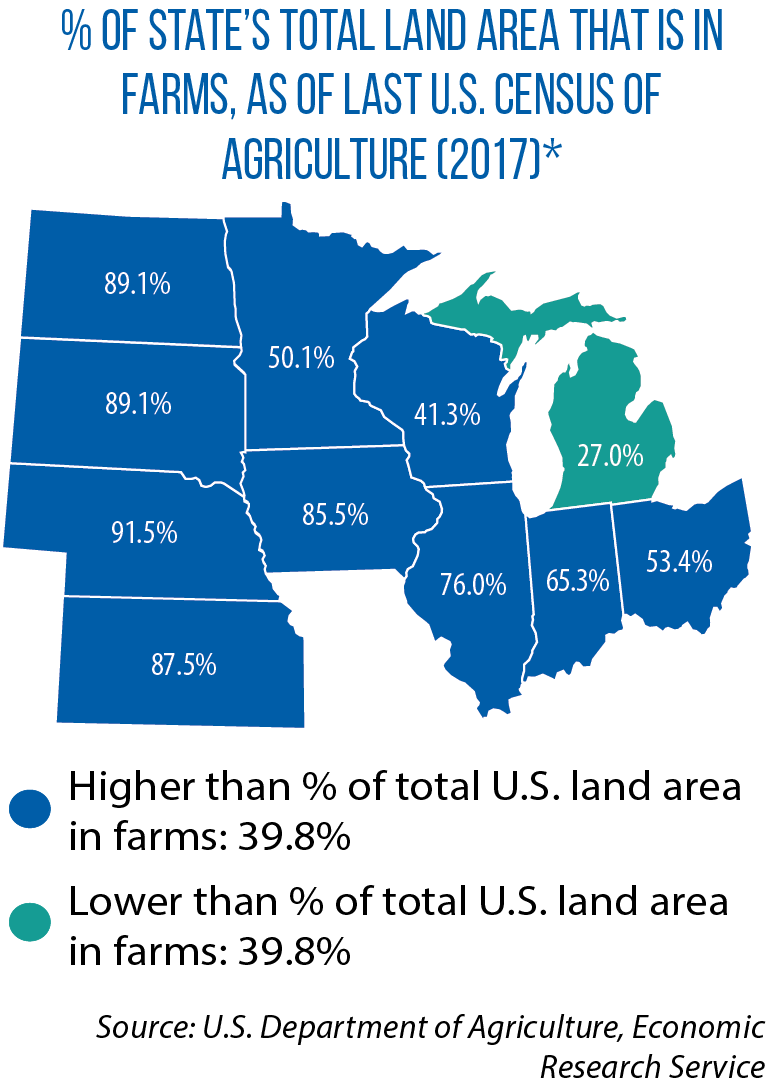

“No Farms No Food” is the message of the American Farmland Trust, an advocacy group founded more than 40 years ago to save the nation’s farms and ranches from development. The group’s Midwest director, Kristopher Reynolds, says it’s a message that doesn’t always resonate in this region because of the clear abundance of ranchland and farmland: Drive through much of America’s Heartland, and it’s most of what you see.

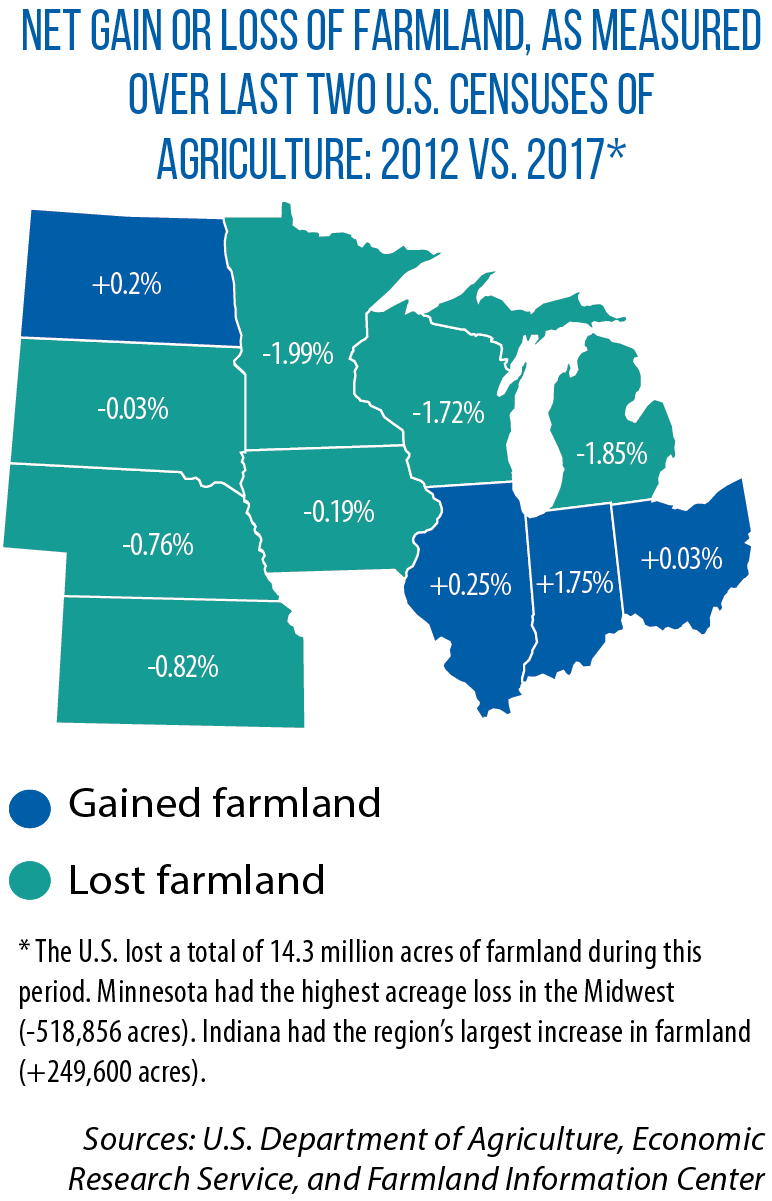

However, many states in this region have lost some of this land to population changes, sprawl and development in recent decades. Looking ahead, it’s not just residential, commercial or industrial development in new areas that could replace farmland.

However, many states in this region have lost some of this land to population changes, sprawl and development in recent decades. Looking ahead, it’s not just residential, commercial or industrial development in new areas that could replace farmland.

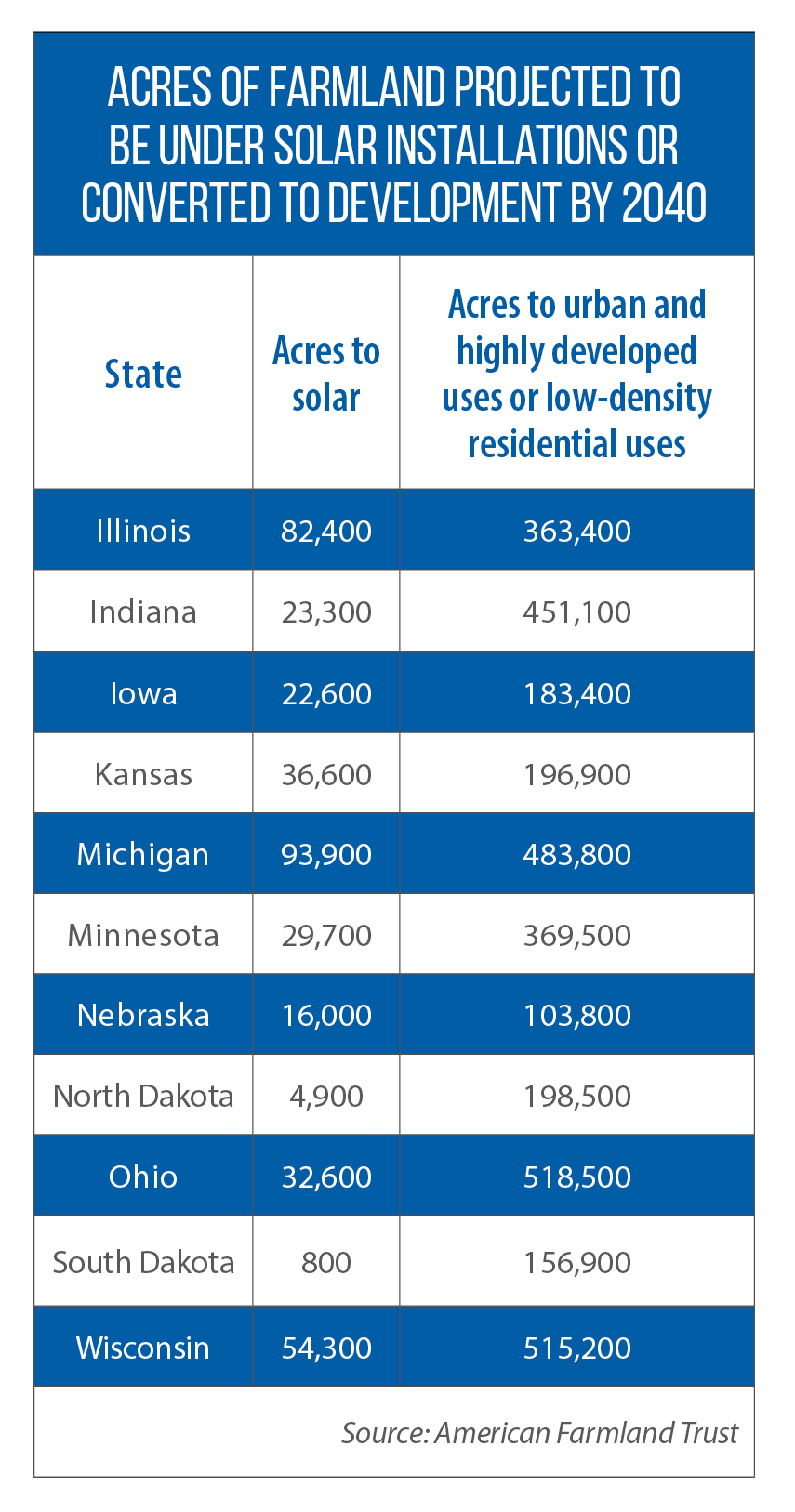

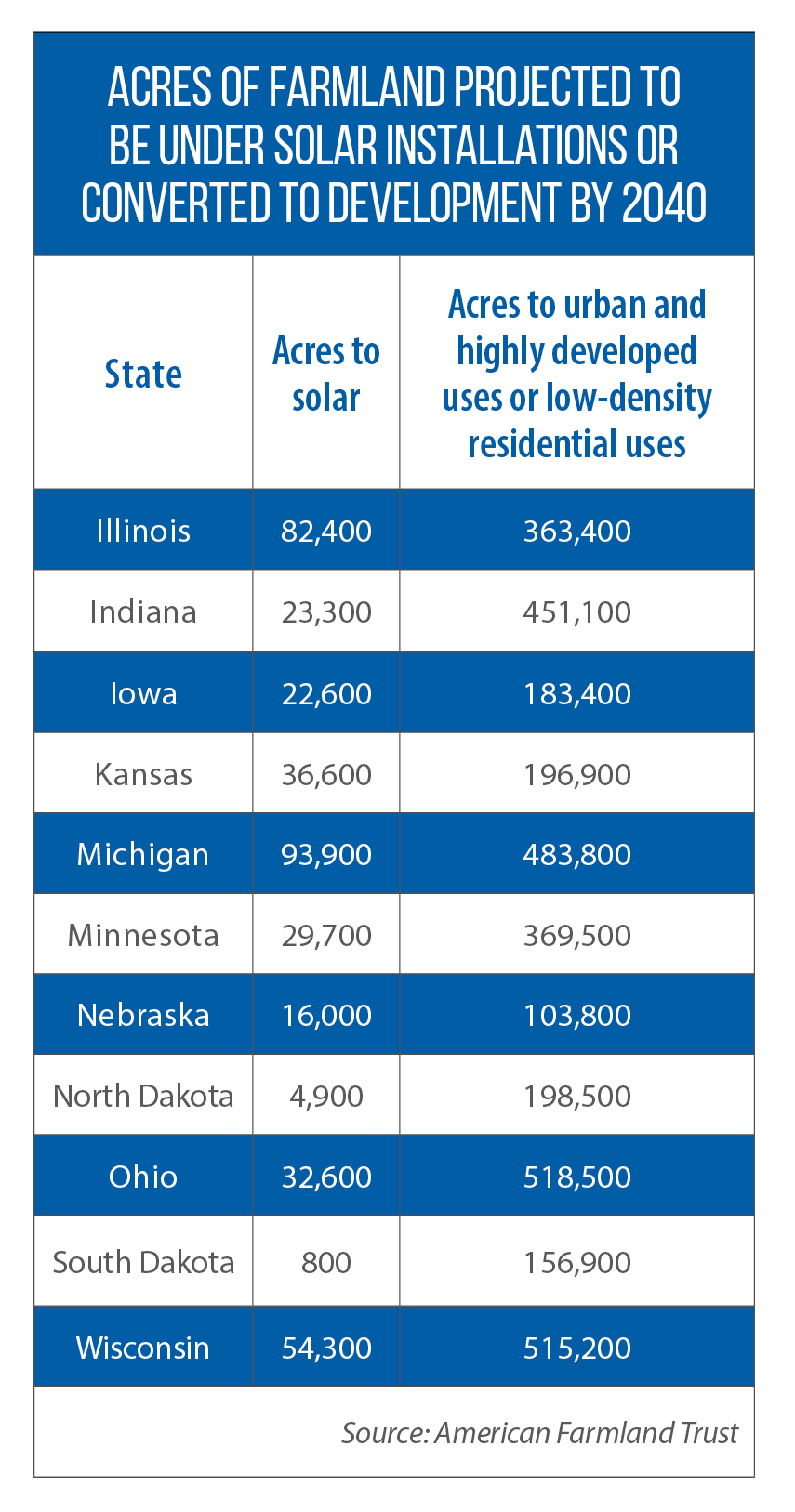

The American Farmland Trust notes in a 2022 national study that “tens of millions of additional acres of rural land will be used for energy production and transmission in the coming decades.” Add to that increases in global population and the likelihood of more-frequent extreme weather events such as droughts and flooding, and keeping “nationally significant” agricultural land in production becomes important for “long-term food security and environmental health,” the authors note in that same report.

No region has a higher concentration of that “nationally significant” land than the Midwest. For states, Reynolds says, these trends point to the need for new policies that stop low-density sprawl, that incentivize or help farmers to keep prime agricultural land in production, and that limit the loss of this land to the continuing rise in energy projects.

“As an organization, we support renewable energy, but we also recognize that it can come at a cost to farmers and to farmland,” Reynolds says. “What we’ve tried to do is identify areas [for renewable projects] that are maybe less productive in terms of agriculture — brownfield sites, for instance — or look for ways where you can still have agriculture production and solar development at the same site.”

‘Once it’s out …’

The pinch on agricultural land is being felt in Wisconsin as well. According to Sen. Patrick Testin, his state has lost nearly 1 million acres over the last two decades, and he worries about future declines due to pressures not just from other types of development or uses, but to some longstanding demographic and economic trends.

The pinch on agricultural land is being felt in Wisconsin as well. According to Sen. Patrick Testin, his state has lost nearly 1 million acres over the last two decades, and he worries about future declines due to pressures not just from other types of development or uses, but to some longstanding demographic and economic trends.

“Like in many states, the average age of our farmer is increasing, and that next generation hasn’t necessarily been there to take up the mantle,” Testin says. “And we’ve seen some of our smaller operations go out of existence.”

One policy lever used by Wisconsin since 1977 is the state’s Farmland Preservation Program. Under the program, local governments have the authority to develop farmland preservation plans and zoning districts, as well as to petition the state for approval of Agricultural Enterprise Areas (AEA). With these AEA designations and zoning districts in place, local farmers then have the opportunity to access state income tax credits by entering into a farmland preservation agreement.

Under this agreement, a farmer agrees to keep the land in agricultural use for 15 years and meet the state’s soil and water conservation standards. The tax credit is $5 per acre for land in an AEA; $7.50 for land in a certified farmland preservation zoning district; and $10 for land in an AEA and a farmland preservation zoning district.

According to the Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection, as of July 2021, a total of 1,061 preservation agreements had been signed covering close to 233,000 acres. Many more acres of land are eligible but not enrolled in the program.

Testin says this lack of participation points to two problems with the current program: the length of the agreement is too long (individuals don’t want to be wedded to 15 years), and the tax credits are too small. He and other legislators introduced bills this year (SB 134 and AB 133) to address both those concerns. The term of the agreement would be reduced from 15 years to 10, and the per-acre tax breaks would be increased and automatically rise in the future with inflationary changes.

“What we’re trying to do with this bill is encourage more people to participate, first of all, and then encourage more farmers to put more acreage into it,” says Wisconsin Rep. Katrina Shankland, another sponsor of the bill.

“What we’re trying to do with this bill is encourage more people to participate, first of all, and then encourage more farmers to put more acreage into it,” says Wisconsin Rep. Katrina Shankland, another sponsor of the bill.

She views increased participation as a win-win-win for the state: Reward farmers for being good stewards of the land, advance the state’s conservation goals, and help preserve Wisconsin’s agricultural heritage.

“Once it’s out of [agricultural] production, it’s rarely, if ever, farmed again,” Shankland says.

‘Best opportunity for states’

Reynolds suggests that states in the Midwest develop and invest in new Purchase of Agricultural Conservation Easement programs; as of January 2022, only Michigan, Ohio and Wisconsin had any farmland acreage protected via a PACE program, according to the American Farmland Trust’s Farmland Information Center.

Under a PACE program, landowners are compensated for keeping their land for agricultural use; the compensation amount is based on the property’s fair market value.

Under a PACE program, landowners are compensated for keeping their land for agricultural use; the compensation amount is based on the property’s fair market value.

“It’s probably the best opportunity for states to protect more farmland because they’re able to leverage federal dollars,” Reynolds says.

That money comes from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Conservation Easement Program. The Inflation Reduction Act, signed into law in 2022, authorized an additional $1.4 billion for this program over the next five years. Accessing those funds, though, requires a 50 percent match. States can fill that void, and tap into newly available federal dollars, by creating a PACE program.

“We’re not making any more farmland, so we need to protect what we have — not just for production purposes, but from what we’re seeing with some of the climate projections and how it’s going to be more difficult to grow food in some other places,” Reynolds says.

“There’s also the issue of farmland changing hands at a rapid pace over the next 15 years. We want to make sure that the next generation still has access to farmland in the future.”

Michigan Sen. Roger Victory has chosen “Food Security: Feeding the Future” as the focus of his CSG Midwestern Legislative Conference Chair’s Initiative for 2023.

EXAMPLES OF STATE POLICIES TO PRESERVE FARMLAND

- Establish agricultural districts in state statute that allow local governments to identify areas where commercial agriculture will be protected and enrolled farmers will get tax benefits of some kind.

- Reduce the amount of money that agricultural producers must pay in local property taxes through the use of a differential assessment system.

- Create ‘right to farm’ laws that provide legal protections to agriculture producers and protect them from local anti-nuisance ordinances.

Source: American Farmland Trust

The post Laws reflect interest in, concerns about future of Midwest farmland appeared first on CSG Midwest.

She lives in and represents a part of North Dakota’s coal country.

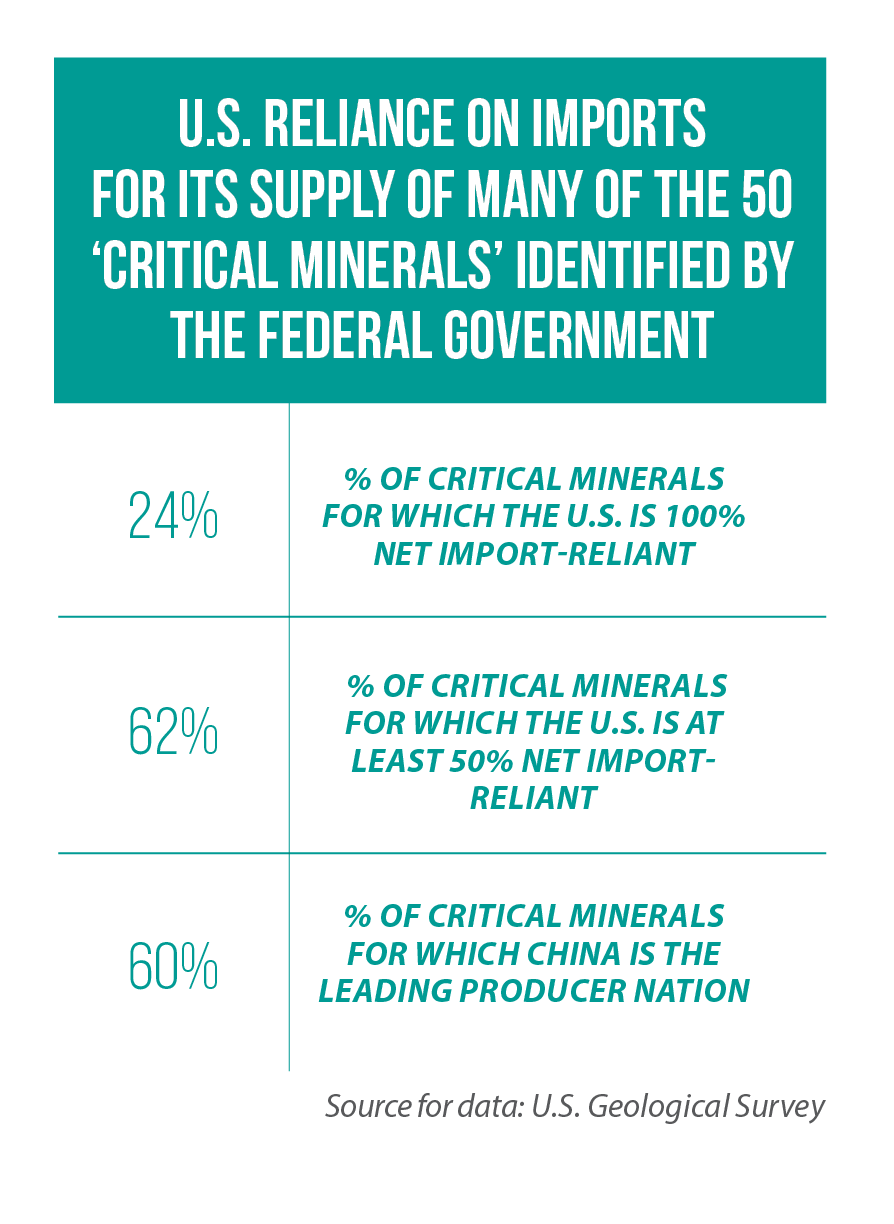

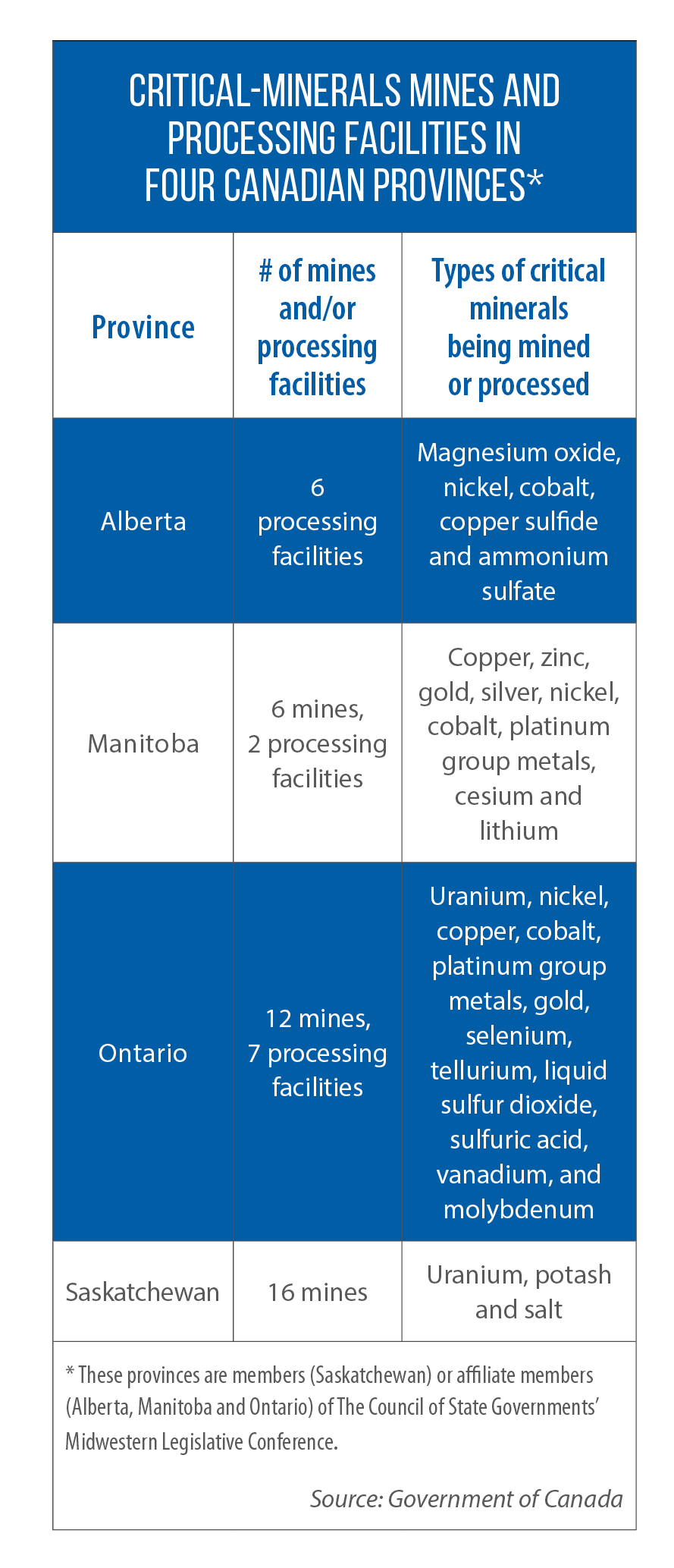

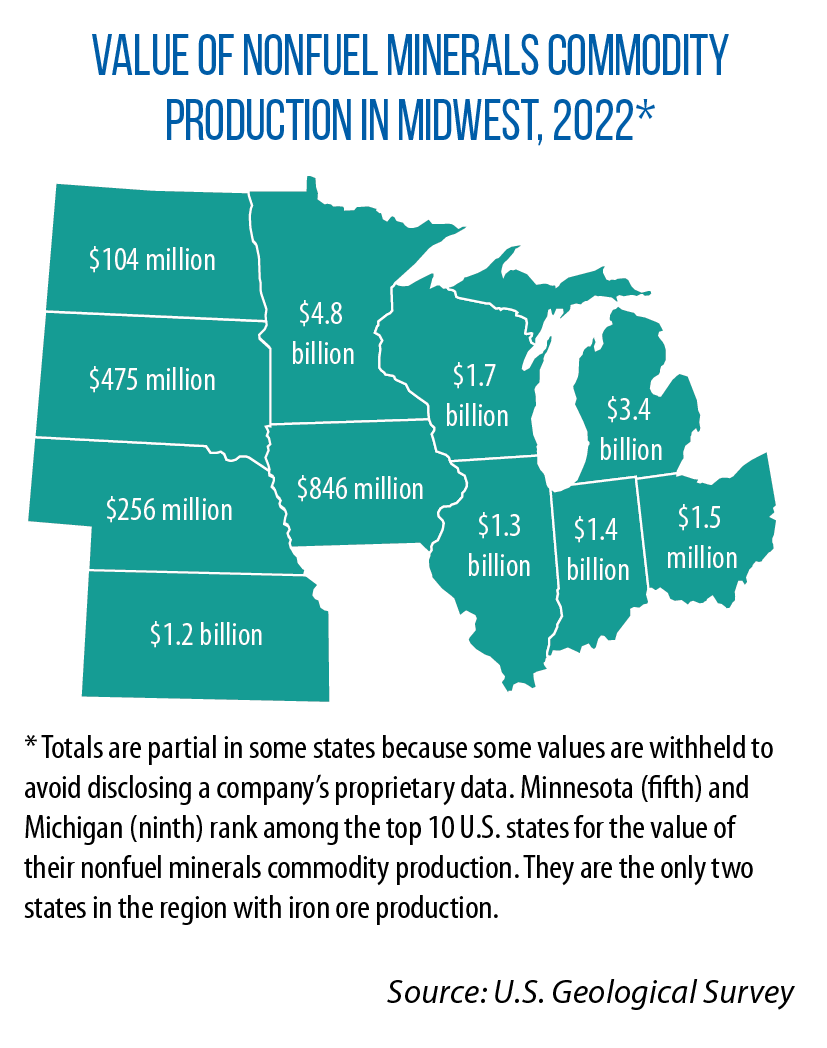

She lives in and represents a part of North Dakota’s coal country. Mineral resources, such as lithium, cobalt, nickel, and rare-earth elements are essential components of batteries, electric motors, and many other advanced technologies.

Mineral resources, such as lithium, cobalt, nickel, and rare-earth elements are essential components of batteries, electric motors, and many other advanced technologies. New federal laws, programs and investments also are in place to increase domestic production.

New federal laws, programs and investments also are in place to increase domestic production.

Rep. Kendell Culp grows corn and soybeans and raises beef cattle in a part of Indiana with some of the most productive agricultural land in the entire state.

Rep. Kendell Culp grows corn and soybeans and raises beef cattle in a part of Indiana with some of the most productive agricultural land in the entire state. “Measuring the acres lost is important,” Culp says, “but just as important is what it’s being lost to.”

“Measuring the acres lost is important,” Culp says, “but just as important is what it’s being lost to.” However, many states in this region have lost some of this land to population changes, sprawl and development in recent decades. Looking ahead, it’s not just residential, commercial or industrial development in new areas that could replace farmland.

However, many states in this region have lost some of this land to population changes, sprawl and development in recent decades. Looking ahead, it’s not just residential, commercial or industrial development in new areas that could replace farmland. The pinch on agricultural land is being felt in Wisconsin as well. According to Sen. Patrick Testin, his state has lost nearly 1 million acres over the last two decades, and he worries about future declines due to pressures not just from other types of development or uses, but to some longstanding demographic and economic trends.

The pinch on agricultural land is being felt in Wisconsin as well. According to Sen. Patrick Testin, his state has lost nearly 1 million acres over the last two decades, and he worries about future declines due to pressures not just from other types of development or uses, but to some longstanding demographic and economic trends. “What we’re trying to do with this bill is encourage more people to participate, first of all, and then encourage more farmers to put more acreage into it,” says Wisconsin Rep. Katrina Shankland, another sponsor of the bill.

“What we’re trying to do with this bill is encourage more people to participate, first of all, and then encourage more farmers to put more acreage into it,” says Wisconsin Rep. Katrina Shankland, another sponsor of the bill. Under a PACE program, landowners are compensated for keeping their land for agricultural use; the compensation amount is based on the property’s fair market value.

Under a PACE program, landowners are compensated for keeping their land for agricultural use; the compensation amount is based on the property’s fair market value.